An 18th century courtship:

The 2nd Earl of Chatham

and

Mary Elizabeth Townshend

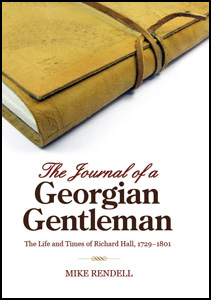

Thank you for the opportunity to write for your blog, Susana. I’m not an author of historical romance (my latest book is straight-up non-fiction), but that doesn’t mean there’s no romance in what I write. Human nature hasn’t changed much in two hundred years. The late Georgian/Regency aristocracy undoubtedly had its fair share of rakes, adulterers and unfaithful lovers, but there were exceptions, and the subject of my biography was one of them.

One of the reasons I was attracted to write about John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham is that he was so refreshingly human. He was closely related to two prime ministers – his father was William Pitt the Elder, and his brother was William Pitt the Younger, both of whom were massive over-achievers, but John was the family black sheep. Everyone expected great things of him, but he never managed to match the greatness of his immediate relatives. On the contrary, he managed to become infamous after he commanded the British expedition to Walcheren in 1809. It was a huge disaster, partly because more than a quarter of the British army came down with malaria.

John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, ca 1779. Detail from John Singleton Copley, ‘The Death of the Earl of Chatham’.

John was a complex character, a product of his parentage and of his times. One thing, however, made him very accessible to me: his love for his wife. John’s marriage lasted thirty-eight years and was childless, but he and his wife were unusually close for aristocrats of the times. They went through some very hard times, but what I want to talk about here is their courtship, which was wonderfully bashful and bumbling.

Mary Elizabeth Townshend, the object of John’s affections, was born in September 1762. She was the second daughter of Thomas Townshend, later Lord Sydney (after whom the city in Australia was named), who was an old friend and political acolyte of Pitt the Elder. Townshend’s estate was very close to Pitt the Elder’s, and the Pitt and Townshend children grew up close.

Mary Elizabeth Townshend, Countess of Chatham, possibly by Edmund Miles

By the time John was twenty-two, his friendship with Mary had deepened. Between June 1778 and March 1779 he was away pursuing his military career in Gibraltar, but the British ambassador to Spain noticed the young man’s heart belonged to another. ‘I would not swear that he is not in possession of a most precious jewel,’ the ambassador told his brother, who later met John in England at Thomas Townshend’s house and worked out what was going on: ‘If he [John] has a mind to set that jewel which you suppose him possessed of very beautifully, he might consult Miss Mary Townshend.’

John and Mary had fallen in love, but Mary was only sixteen and John was in any case too bound up in his military career. He was sent off to the West Indies in early 1780 and was not able to guarantee his long-term presence in England until he transferred to a London-based regiment in 1782. At this point he began to press his suit more vigorously, and by June 1782 John’s brother William informed their mother of ‘a match of which the world here is certain, but of which [John] assures me he knows nothing, between himself and the beauty in Albemarle Street’ – Albemarle Street being Thomas Townshend’s London residence.

But John was a typical boy, and it turned out he wasn’t quite ready to commit just yet. (He was enjoying bachelorhood far too much, going to see the horse racing in Newmarket, hunting with his great friend the 4th Duke of Rutland, and sitting up late at White’s and Brooks’s to gamble at cards.) Whenever anyone questioned him about his forthcoming marriage, he dismissed the rumours with dry sarcasm as ‘stock jobbing reports’.

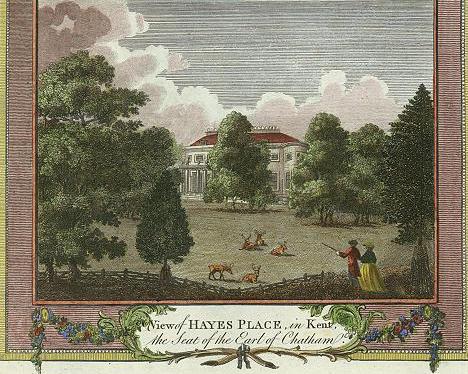

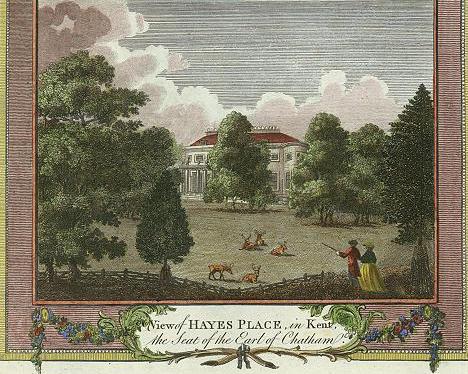

By May 1783, however, John himself had begun to believe in his own love-story. On the first of the month he took his sister Harriot on a carriage ride to his country seat, Hayes Place. Harriot wrote to their mother that the family home was ‘just now in glory, and I think my brother enjoyed very much contemplating his pretty place and thinking of the pretty lady he means to give it.’

Hayes Place, Kent

A few days later Harriot reported excitedly that John and Mary had been so publicly ‘amicable’ at a ball that she was ‘really disappointed when I found the matter was not settled there.’

It was at this point that John decided to show his colours as a man with all the gumption and emotional intelligence of a thirteen-year-old. Soldier he might be, but he simply couldn’t muster the courage to pop the question. He accepted an invitation from the Townshends to accompany the family on a weekend away, where, as Harriot pointed out meaningfully, he was purposefully provided with ‘opportunities’ to declare his feelings. Did he propose? Did he heck. He ‘had only very near[ly] done it once.’

Lady Harriot Pitt, John’s sister, by an unknown artist

Perhaps it was a romcom situation, in which the critical moment was interrupted by a family member, or a sudden crisis, or an explosion, or something like that. (Most likely John just bottled out: ‘Mary?’ ‘Yes?’ ‘……… Could you please pass the salt?’)

Either way, a week after Harriot had been eagerly anticipating her brother’s proposal, nothing had happened and the bride-to-be was getting ‘not a little fidgetty’. Even John’s brother William, who famously had no time for romance, could see that it was ‘full time’ the courtship ‘should end. I rather home it will be happily completed very soon, though it has lasted so long already that it may still last longer than seems likely.’

But by the end of May John still hadn’t proposed. He was getting very frustrated with his family, who were very close to beating him over the head with the nearest convenient blunt instrument if he didn’t make up his mind. ‘My brother and I have been beating over the same ground again,’ Harriot grumbled. ‘… I think in this sort of way all sides may be likely to get frampy.’ No idea where frampy came from (it’s not an 18th century word I recognise), but its meaning was clear.

And yet another two weeks passed in this way before John finally screwed up the courage and proposed on 5 June. Despite Harriot’s fears that she would be too fed up to accept, Mary accepted on the spot.

The marriage licence was applied for, and on 5 July 1783 John, his bride and his future father-in-law put their pens to a ten-page vellum marriage settlement bestowing a dowry on Mary of £5000, partly out of family funds and partly out of West India stocks.

John and Mary’s marriage settlement, Bromley Archives Marsham Townshend MSS 1080/3/1/1/26

The marriage itself took place in Mary’s father’s Albemarle Street house on 10 July 1783. Mary was given away by her father, whose permission had been required to secure the marriage licence, as she was still only twenty and therefore considered a legal minor. (The marriage licence described her as ‘an infant under the age of twenty-one years’, which made it sound a bit like John was a cradle-snatcher.)

John and Mary’s crests, from a family pedigree (private collection)

‘The person that constitutes the happiness I so truly feel, is Miss Mary Townshend,’ John wrote delightedly to an old family friend shortly before the marriage. ‘… How much reason on every account I have to be so, I flatter myself all who know her will readily allow.’

Mary’s reaction is not recorded, but she must have been equally relieved.

Book Depository

References

Letters between Lord Grantham and Frederick Robinson, 1779, Bedfordshire Archves Wrest Park (Lucas) MSS L30/15/54/139 and L30/14/333/211.

Letters of Lady Harriot Pitt, John Rylands Library, University of Manchester GB 133 Eng MS 1272, ff. 32-45.

Bromley Archives, Marsham-Townshend MSS 1080/3/1/1/26.

Pitt Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Books and Manuscripts Library, Duke University, USA.

Earl Stanhope, Life of Pitt, 4 vols. (London, 1861).

About the Author

Jacqueline Reiter has a PhD in late 18th century political history from the University of Cambridge. A professional librarian, she lives in Cambridge with her husband and two children. She blogs at www.thelatelord.com and you can follow her on Facebook (www.facebook.com/latelordchatham) or Twitter (https://twitter.com/latelordchatham). Her first book, The Late Lord: the life of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, was published by Pen & Sword Books in January 2017.