A House in Bow Street

Crime and the Magistracy

London 1740-1881

Anthony Babington, 1969

Henry Fielding at Bow Street

From Wikipedia:

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English novelist and dramatist known for his rich, earthy humour and satirical prowess, and as the author of the picaresque novel Tom Jones. Additionally, he holds a significant place in the history of law enforcement, having used his authority as a magistrate to found (with his half-brother John) what some have called London’s first police force, the Bow Street Runners.

At the time of Fielding’s appointment, the position of magistrate was lowly regarded, as a large number of magistrates enriched themselves by taking bribes, charging fees, and running bail bond services.

A lampoon from the journal, Old England:

Now in the ancient shop at Bow,

(He advertises it for show),

He signs the missive warrant.

The midnight whore and thief to catch,

He sends the constable and watch,

Expert upon that errand.

From hence he comfortable draws

Subsistence out of every cause

For dinner and a bottle.

In spite of the fact that the basest motives had been attributed to him in becoming a magistrate, Fielding himself regarded his appointment as something of a challenge—perhaps the greatest and the final challenge of his whole life. He was finished as a playwright, he had failed as a barrister; his only novel had been cordially, but unenthusiastically received; he was burdened with poverty and ill health.

Fielding, already an acting justice for Middlesex, was granted properties valued at £100 a year by the Duke of Bedford for the purpose of fulfilling the property qualification for the position. At some point he was sworn in as a justice for Westminster—which had no property qualification—as well. In the autumn of 1748, he took cases in his home near Drury Lane, then to Meard’s Court, St. Anne’s, and by December had moved to the Bow Street Office.

By sheer good fortune Henry Fielding was brought into contact at that time with two honourable men, Joshua Brogden and Saunders Welch, both of whom shared his views and were ready to join to the utmost in his endeavours. Brogden, who became his clerk at the Bow Street Office, had been a magistrate’s clerk before.

[Saunders Welch] had occupied the position of High Constable of Holburn for about a year when Fielding came to Bow Street. The office of High Constable was a part-time function which usually lasted for a duration of between one and three year. As a rule, it was performed by a successful tradesman—Saunders Welch was a grocer—and carried no official remuneration apart from a limited scale of allowances, although there were, of course, ample opportunities for illicit profit. Considering the period in which he lived, Saunders Welch was a high constable of quite exceptional honesty and skill. In fact, after working with him for six or seven months, Henry Fielding said he was ‘one of the best officers who was ever concerned in the execution of justice, and to whose care, integrity, and bravery the public hath, to my knowledge, the highest obligations.’

Initial Reforms

In order to provide for his own financial maintenance—and being unwilling to participate in the unscrupulous methods of boosting income used by his predecessors—he managed to get the government to pay him a regular salary out of public service money.

One of his first actions was to keep accurate reports and publish them in the newspapers.

Before Henry Fielding arrived at Bow Street there could have been very few, if any, full and authentic reports of the proceedings which took place at a magistrate’s house or his office. However, from the outset, Fielding arranged for the details of his cases, written by his clerk, Joshua Brogden, to be published regularly in certain newspapers. His object was not self-publicity, but rather to inform as wide an audience as possible of the types of offence then prevalent, the steps he was taking to overcome them, and to give an occasional dissertation on the requirements of the criminal law.

The following appeared in the St. James’s Evening Post in mid-December, 1748. This account of a committal to prison of a man who had attacked and wounded a young woman with a cutlass ended:

It is hoped that all Persons who have lately been robb’d or attack’d in the Street by Men in Sailor’s Jackets, in which Dress the said ones appeared, will give themselves the trouble of resorting to the Prison in order to view him. It may perhaps be of some advantage to the Publick to inform them (especially at this time) that for such Persons to go about armed with any Weapon whatever, is a very high Offence, and expressly forbidden by several old Statutes still in force, on Pain of Imprisonment and Forfeiture of their Arms.

This was one of the earliest of Fielding’s celebrated ‘admonitions’ to the public which were to play such a large part in his campaign against crime during the next few years.

Henry Fielding’s Charge

A month after his election to the Chair of Westminster Sessions, Henry Fielding was called upon to deliver a Charge to the Grand Jury of Westminster. This event took place on the 29th June, 1749, and it must have been a significant occasion for him as it was the first time since becoming a magistrate that he had been given the opportunity of making an official pronouncement. Fielding’s fellow justices were so impressed by his Charge that they passed a resolution asking him to have it printed and published, ‘for the better information of the inhabitants and public officers of this City and Liberty in the performance of their respective duties.’ The Monthly Review commented: ‘This ingenious author and worthy magistrate, in this little piece, with that judgment and knowledge of the world, and of our excellent laws (which the publick, indeed, could not but expect from him) pointed out the reigning vices and corruptions of our times [and] the legal and proper methods of curbing and punishing them…’

The War Against Crime

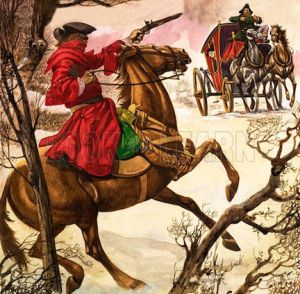

The 1740’s in London was a time when the highwayman, the footpad, and the house-breaker ran rampant over weak and ineffectual peace-officers, and even when a criminal was captured, there was insufficient room in jails to accommodate them.

Henry Fielding was possessed of certain qualities which would have enabled him to become an outstanding magistrate… He had a fearless independence of spirit, a complete impartiality of approach, a breadth of human understanding, and an infinite knowledge of law and procedure. He felt very little emotional affinity with his own social class. In 1743 he wrote that, ‘the splendid palaces of the great, are often no other than Newgate with the mask on’: and added, ‘a composition of cruelty, lust, avarice, rapine, insolence, hypocrisy, fraud and treachery, glossed over with wealth and title have been treated with respect and veneration, while in Newgate they have been condemned to the gallows’.

…under Henry Fielding the Bow Street Office, whilst remaining a private room in a magistrate’s ordinary residence, was conducted on the lines of a superior court, in an atmosphere of judicial dignity and according to the strictest principles of legal propriety. The office continued to be maintained solely out of the fees which were recoverable by law and by custom from arrested persons, prisoners and applicants for process.

Fielding’s office dealt with serious crimes such as burglary, assault, riot, coining, brothel-keeping, and smuggling as well as minor ones such as drunkards, gamblers, prostitutes, vagrants and beggars.

The justice administered by Henry Fielding was a sagacious blending of sternness, understanding, and compassion. He respected the life and property of the law-abiding citizen, and he knew how easily the delicate structure of society could be imperilled by the forces of disorder; therefore, he wasted little sympathy on the robber, the armed thug, the vandal or the rioter. On the other hand, he felt the deepest pity for the neglected victims of an economic system founded upon inhumanity and self-interest.

Fielding, while he had no qualms about sending juveniles and first-offenders to prison, advocated for less severe penalties for small thefts. He particularly criticized the sentencing of vagrants to houses of detention for the wantonly idle.

What good consequence can there arise from sending idle and disorderly persons to a place where they are neither corrected or employed, and where with the conversation of many as bad, and sometimes worse than themselves, they are sure to be improved in the knowledge, and confirmed in the practice of iniquity?

Employing the assistance of the law-abiding

With no centralised police force, and no effective liaison between the peace officers of the various parishes, it was extremely difficult to achieve even a limited co-rdination of effort. To overcome this obstacle Fielding decided to make a direct appeal to the public.

NOTICE AND REQUEST TO PUBLIC

All persons who shall for the future suffer by robbers, burglars, etc., are desired immediately to bring or send the best description they can of said robbers etc., with the time, place, and circumstances of the fact to Henry Fielding,Esq. at his house in Bow Street, or to John Fielding Esp. at his house in the Strand. [John was his brother, who continued Henry’s work after his death.]

Fielding insisted on the cooperation of the law-abiding, not only for the purpose of making reports, but also in attending his examinations of prisoners in order to make identifications.

Fielding’s thief-takers

The pre-cursors of the force later known as Bow Street Runners, Fielding’s “thief-takers” was a group of six ex-constables under the command of his lieutenant, Saunders Welch. These men were on call to be summoned to pursue villains at any moment.

After a robbery or a house-breaking, a message would be rushed to Bow Street, and the thief-takers, or as many of them as were available, would set out in immediate pursuit. Strangely enough, the system worked remarkably well. This was due partly to the fact that the London criminal had never before been confronted by an organised opposition, and also to the ever-increasing knowledge and proficiency of the thief-takers.

Jack Sheppard, a celebrated criminal of the age, is imprisoned in the gate house at the door of which sits a figure, thought by some to be Jonathan Wild besieged by a crowd of people seeking the return of their stolen property.

Enquiry into the Causes of the Late Increase of Robbers

A treatise published by Fielding in 1751 stated bluntly that

“The streets of this town and the roads leading to it will shortly be impossible without the utmost hazard.” He claimed that even if the robbers were arrested, they would likely be rescued by their own gang, or by bribing or intimidating the prosecutor.

He asserted that the first cause of crime was idleness and public diversions, such as music and dancing halls. Later that year, an Act was passed bringing these entertainments under the supervision of the justices of the peace.

Next, he denounced drunkenness as “the odious vice, indeed, the parent of all others.” “He elaborated on the appalling consequences of the continued vogue of spirit-drinking, and suggested higher taxes on gin, and a much firmer control over the places where it was sold. Many of the provisions of the Gin Acts of 1751 and 1753 were based on his proposals.”

He also criticized rampant gaming and lotteries, and the application of the Poor Law, as well as defects in the criminal law and criminal procedure. A month later, “a Parliamentary Committee was set up… to revise and consider the laws in being, which relate to felonies and other offences against the peace. The Lloyd Committee… was strongly influenced by Henry Fielding’s views and made a number of recommendations which accorded closely with his suggestions. As a result, several statutes were enacted during the next few years which profoundly affected the future development of the British criminal law.”

Another of his proposals was a law be passed making it illegal to receive stolen property, thus making it more difficult for thieves to dispose of their booty. An effort was made to require pawnbrokers to obtain a license, but this was passed.

Fielding condemned the system by which criminal prosecutions had to be brought by, and in the name of, a private individual, for this resulted in a large number of known offenders never being charged at all. The victim of a crime might be deterred from charging the culprit by threats or intimidation; he might be too indolent to embark on legal proceedings; he might be tender-hearted and, in an era when every felony was nominally a capital offence, averse to taking away the life of a fellow-being; above all, he might be unable or unwilling to bear the costs involved in a prosecution [which might mean traveling great distances for himself and potential witnesses]. … The answer to this, Fielding suggested, was that the county or the nation should pay the expenses of all prosecutions. [This proposal was adapted in part and later became implemented more fully in the development of criminal prosecutions financed out of public funds and presented in the name of the Crown.]

Fielding was intensely critical of the frequency of executions, and of the method in which the hangings were carried out. Fundamentally, a public execution was supposed to produce an atmosphere of terror and shame amongst the onlookers, but ‘experience hath shown that the event is directly contrary to this intention’. The triumphal procession from Newgate to Tyburn, the huge crowds; the condemned prisoner’s final speech from the scaffold; the veneration, the excitement, the acclaim—all these tended to turn a day of infamy into a day of glory.

He suggested that executions should be conducted with much greater solemnity and should be witnessed by as few spectators as possible. Further, they should take place very soon after the crime itself, ‘when public memory and resentment are at their height’. At the end of a trial, he said, the court should adjourn for four days, and then the prisoner should be brought back, sentences to death, and executed forthwith just outside the court, ‘in the sight and presence of the judges’.

Fielding’s proposal for speedier executions was “put into effect in 1752 in respect of executions for murder, by an act which provided that, unless the judge knew of reasonable cause for delay, the condemned murderer was to be hanged two days after the passing of sentence.”

Accolades at last for Henry Fielding

The Enquiry was received with interest and with praise; even Horace Walpole, no friend to Henry Fielding, described it as ‘an admirable treatise’. The Monthly Review in January 1751, paid this glowing tribute:

The public hath been hitherto not a little obliged to Mr. Fielding for the entertainment his gayer performances have afforded it, but now this gentleman hath a different claim to our thanks, for services of a more substantial nature. If he has been heretofore admired for his wit and humour, he now merits equal applause as a good magistrate, a useful and active member and a true friend to his country. As few writers have shown so just and extensive a knowledge of mankind in general, so none ever had better opportunities for being perfectly acquainted with that class which is the main subject of this performance.