Breeding and training thoroughbreds for racing was the passion of many wealthy gentlemen of good birth. Even more participated in watching and wagering the races. Newmarket, with its network of race courses, sponsored seven race meetings a year, and a third of all the race horses in England were trained nearby. (Transporting horses was very difficult, and most horses were walked to the race course, so it was better to keep them as near as possible.)

Around 500 spectators—nearly all upper-class—gathered to watch the race on horseback, sitting on top of carriage roofs, or standing around the course at Newmarket, as there were no grandstands as there were at other courses. In 1809, the 2000 Guineas, a sweepstakes for three-year-olds was established at Rowley Mile. The 1000 Guineas, a race for three-year-old fillies was established in 1817 at the less taxing course of Ditch Mile.

Prince George was an enthusiastic participant in racing in his younger days (1788-1791), but withdrew in a huff when the jockey of his horse Escape was involved in a dreadful scandal, and the Jockey Club—the organization that oversaw the sport—insisted that the Prince give the jockey his marching orders. What was the scandal? A matter of Escape losing a race one day, forcing the odds up for the next day, resulting in the Prince winning a large sum of money. The Prince continued to patronize the races, however. He just could not resist the lure of the excitement and gambling.

Types of Races

Horse matches were head-to-head contests where individual owners would agree on a wager, and the winner took all. Spectators would make side bets as well. In one famous match, Hambletonian vs. Diamond, almost 300,000 pounds changed hands.

Plate and cup matches, where the prize was a trophy, were quite common as well.

The sweepstakes, however, with a line-up of horses running against each other, was the most popular in the late 18th/early 19th century. The owners put up a specified sum to subscribe to the race, and the winner took everything.

Race Courses

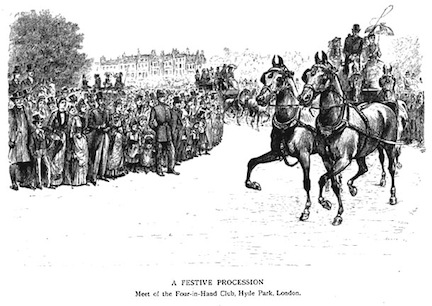

Ascot, with its close proximity to London, became a popular venue for fashionable race fans. In 1814, popular heroes such as Blücher, Tsar Alexander, the King of Prussia and Hetnan Platov provided additional entertainment for the race-mad hordes.

Epsom Downs, home of the legendary horse Eclipse, drew large crowds of the fashionable on Derby Day (named after the Earl of Derby who was instrumental in its development), a one-and-a-half mile race for three-year-olds. The only permanent structure on the course was Prinny’s stand, a miniature “castle” with Gothic arches where he could sit with his cronies to enjoy the races.

Other race courses were Goodwood in Yorkshire, Newcastle, Chester, Warwick, Winchester and Doncaster. Raikes (a dandy, banker and diarist) says:

“The Prince made Brighton and Lewes the gaiest scene of the year in England. The Pavilion was full of guests; the Steyne was crowded with all the rank and fashion from London during that week; the best horses were brought from Newmarket and the North, to run at these races, on which immense sums were depending; and the course was graced by the handsomest equipages.”

The Jockey Club

The organization responsible for regulating the racing world was the Jockey Club, whose members in 1790 included the Prince Regent, the Dukes of Bedford, Cumberland, Devonshire, and Norfolk. The Jockey Club established rules for such things as record-keeping and ensured that they were followed.

Wagering

As in London clubs and gaming hells, fortunes were won and lost at race courses. Brummell, too, lost large sums on horse racing. Raikes says:

“…I was never more surprised than when, in 1816, one morning he confided to me, that he must fly the country that night and by stealth. The next day he was landed in Calais, and, as he said, without any resources. I had several letters from him, at that time written with much cleverness, in which his natural high spirits struggled manfully against his overpowering reverses; but from the first he felt confident that he should never be able to return to his own country.”

Laudermilk, Sharon H. and Hamlin, Theresa L., The Regency Companion, Garland Publishing, 1989.

The Regency Gentleman series

The Regency Gentleman: His Upbringing

The Rise and Fall of Beau Brummell

Gentlemen’s Clubs in Regency London

Gentlemen’s Sports in the Regency