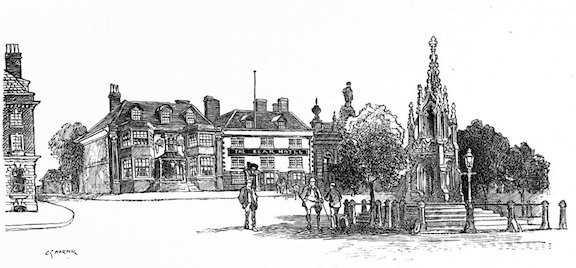

A House in Bow Street

Crime and the Magistracy

London 1740-1881

Anthony Babington, 1969

Thomas de Veil’s London

Some time in 1740 Colonel Thomas De Veil, a justice of the peace for the Count of Middlesex and for the City and Liberty of Westminster, decided to move his magistrate’s office from Thrift Street, now called Frith Street, in Soho to a house at Bow Street in Covent Garden.

The Covent Garden area was once pasture land owned by the Abbots of Westminster. Later, it became the site of Inigo Jones’s famous Piazza, with fashionable terraced houses and a small church. The nobility and the gentry scrambled to build homes here.

By the beginning of the eighteenth century the character of Covent Garden was undergoing a perceptible change. It was, perhaps, inevitable that the ultra-fashionable Piazza and the locality all about it should attract a swarm of tradesmen, artisans and others who were needed to cater for the requirements of the wealthy. At the same time the narrow passages, the darkened alleys, and the secluded courtyard which separated the streets and the houses drew in a far less respectable segment of the community. Another factor affecting the type of inhabitant settling in the neighbourhood was the continual tendency of the nobility and the aristocracy to drift westwards as other areas were developed further and fruther from the walls of the City. Soon after the Restoration the newly-built St. James’s Square superseded the Piazza as the centre of fashion, and in the early days of the eighteenth century Mayfair was further developed with the setting up the palatial mansions of Cavendish Square, Hanover Square and Grosevenor Square. However, one of the major factors which contributed to the transformation of Covent Garden was that it was becoming the principal artistic and theatrical locality of London.

Actors and actresses and their audiences flocked to theaters such as Drury Lane, the Opera House, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and Covent Gardens. Literary folk and ‘wits’ flocked to the coffee-houses such as Will’s, Buttons’s, and Tom’s. When Tom King died, his widow turned his coffee-house into a brothel. And so it was that “the streets of Covent Garden and the Strand became the chosen haunts of the prostitutes.”

“An age of lawlessness and disorder in which the power of the mob and the violence of the criminal were ever paramount”

It was becoming obvious that the current system of policing was inadequate. Streets were especially dangerous at night due to the lack of a proper lighting system.

Pickpockets

A guidebook of the period warned its readers: “A man who saunters about the capital with pockets on the outside of his coat deserves no pity.” As shown by Charles Dickens in Oliver Twist, young boys and girls could be very deft at this particular offense. Richard Oakey would trip up a woman from behind and remove her pocket (pockets dangled from the waist on the outside of a woman’s dress) before she hit the ground. Mary Young had a pair of artificial arms made so that she could sit primly in a church pew with the artificial arms folded on her lap while she used her real arms to rob from those sitting next to her.

Footpads

Henry Fielding said that the alleys, courts and lanes in London were “like a vast wood of forest in which a thief may harbour with as great security as the wild beasts do in the deserts of Africa or Arabia.” And not just at night either. Fanny Burney complained about footpads and robbers before breakfast.

Criminals operating in gangs made the situation even worse. In 1712, a band of thugs called the Mohocks would greet people in the streets and if they responded, beat them up. They attacked the watch in Devereux Court and Essex Street; they also slit two people’s noses, and cut a woman in the arm with a pen-knife. One night about twenty of them stormed the Gatehouse, wounded the jailor, and released their confederate from the jail.

No person was safe and equally no home was secure. Madam Roland… said that when the wealthy left London in the summer they took with them all their articles of value or else sent the lot to their bankers, because ‘on their return they expect to find their houses robbed.’

Highwaymen

The highwaymen were regarded both by the public and amongst the criminal fraternity as being the princes of the underworld. It is difficult to understand why they had so glamorous a reputation in the eighteenth century and, indeed, why their image has been so romanticised ever since. By and large they were simply robbers on horseback and many of them had deplorable backgrounds. Dick Turpin’s gang, for example, was well-known for violence, terrorism, rape, and even murder.

Their favorite hunting-grounds were the roads just outside London. For that reason, dwellers of the suburban areas organized vigilante patrols, and in some areas, squads of soldiers were used to escort travelers in and out of town. Horace Walpole told of an attack on a post-chaise outside his home in Piccadilly, and also of a personal encounter with two of them in Hyde Park.

Why the mounting lawlessness?

Some blamed it on the “large numbers of disbanded soldiers and sailors roaming the country without work and without subsistence. Others held that it was due to drunkenness and cheap gin. A few—but a very few—saw a possible cause in the harsh administration of the Poor Laws and the way in which homeless and the destitute were hounded from parish to parish, coupled with the terrible social conditions of the poor.”

Whatever the reasons, the precincts of the capital and its approaches were deteriorating into a state of lawlessness which bordered on anarchy, and the machinery for preserving the peace was becoming increasingly impotent. The ancient system with its corner stones in the amateur magistrate and the part-time constable, had worked comparatively well throughout the ages in the rural areas of Britain but had proved completely unadaptable to an expanding urban community. At the beginning of the eighteenth century the basic problem remained unsolved—and barely appreciated.

It was in a London such as this that Colonel Thomas De Veil opened his Office at Bow Street.

The Four Times of the Day

The Four Times of the Day, a series of paintings by Hogarth in 1738, illustrated the sort of place Covent Garden had become. Read more about it here.