published by Rudolph Ackermann in 3 volumes, 1808–1811.

ASTLEY’S AMPHITHEATRE.

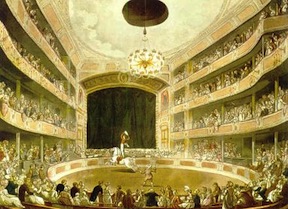

The Amphitheatre at Westminster bridge has, within these twelve years, been twice destroyed by fire; and the expence of rebuilding, & c. &c. to Messrs. Astleys, the two proprietors, has been estimated as amounting to nearly thirty thousand pounds. The present theatre is the most airy, and in some respects the most beautiful, of any in this great metropolis. The building is one hundred and forty feet long; the width of that part allotted to the audience, from wall to wall, sixty-five feet; and the stage is one hundred and thirty feet wide, being the largest stage in England, and extremely well adapted to the purpose for which it was built, the introduction of grand spectacles and pantomimes, wherein numerous troops of horses are seen in what has every appearance of real warfare, gallopping to and fro, &c. &c. The whole theatre is nearly the form of an egg; two thirds of the widest end forms the audience part and equestrian circle, and the smaller third is occupied by the orchestra and the stage. From this judicious arrangement, the whole audience have an uninterrupted prospect of the amusements. It is lighted by a magnificent glass chandelier, suspended from the center, and containing fifty patent lamps, and sixteen smaller chandeliers, with six wax-lights each. The scenery, machinery, decorations, &c. have been executed by the first artists in this country, under the immediate direction of Mr. Astley, jun. who made the fanciful design.

A very good idea of its general appearance, company, &c. is given in the annexed print.

For a looker-on to describe some part of the amusements would be difficult, perhaps impossible; and luckily it is not necessary, for in an advertisement published November 1807, Mr. Astley himself has described one of them in a manner so singularly curious, that we think it ought to be transmitted to posterity; and have therefore inserted it in this volume.

“TO THE EDITOR OF THE MORNING CHRONICLE.

“Sir,

“Having been strongly requested to give some explanation of the utility of the country dances by eight horses, to be performed this and tomorrow evening, I request you will be so obliging as to insert the following hints.

“First, I humbly think that a thorough command and pliability on horseback, is obtained by such noble exercises. Secondly, that in executing the various figures in this dance, the rider obtains a knowledge of the bridle hand, also capacity and capability of the horse, more particularly at the precise time of casting off and turning of partners, right and left, &c. &c. Thirdly, I also conceive that the horseman may be greatly improved when in the act of reducing the horse to obedience on scientific principles! ! ! and not otherwise. Fourth, as a knowledge of the appui in horsemanship is highly desirable, whether on the road, the chase, or field of honour, I expressly composed the various figures in the country dance for this desirable purpose; and which my young equestrian artists have much profited by, as some of them three months since were never on horseback. It was from this observation, during forty-two years practice, that I gave this equestrian ballet the name of L’Ecole de Mars; and I am strongly thankful that my humble abilities have afforded some little information, as well as amusement, to the town in general.

“I am, with respect,

“The public’s most humble and faithful servant,

“Philip Astley.”

Pavilion, Newcastle-street, Strand .”

From all this, a spectator would be almost tempted to think, that, notwithstanding the numerous and learned dissertations of philosophers to exalt their own species, horses rival man in his superior faculties. I have heard a story on this subject, which I believe has not found its way into Joe Miller; but be that as it may, it is a good story, and in a degree illustrates this subject, and I think my reader will not be displeased at the insertion of it.

Some years ago, a very learned and sagacious doctor of the university of Oxford, composed and read a long lecture on the difference of man from beast; and when describing the former, asserted that man was superior to all other animals; because there was no other animal, except man, who either reasoned or drew an inference, as the inferior order of beings were wholly governed by instinct.

On the conclusion of this philosophical discourse, two of the students, who were not quite satisfied of the fact, walked out to converse upon it, and seeing a house with “Wiseman, drawing master,” inscribed upon the sign, went into the shop, and asked the master what he drew? “Men, women, trees, buildings, or any thing else,” was the reply. “Can you draw an inference?” said one of them. The man took a short time to consider it, and candidly replied, that never having seen or heard of such a thing before, he could not. The students walked out of his house, and before they had proceeded far, saw a brewer’s dray with a very fine horse in it.“ A fine horse this,” said one of them to the driver. “A very fine one indeed,” said the fellow.“ Seems a powerful beast,” said the other, “I believe he is indeed,” replied the fellow. “ He can draw a great load, I suppose?” said the Oxonian. “ More than any horse in this county,” answered the drayman. “Do you think he could draw an inference?” said the scholar. “He can draw any thing in reason, I’ll be sworn,” replied the drayman.

The scholars walked back to the lecture room, and found the company still together; when one of them, addressing the doctor with a very grave face, said to him, “Master, we have been enquiring, and find that your definition is naught; for we have found a man, and a wise man too, who cannot draw an inference, and we have met with a horse that can”

Besides the Amphitheatre, Messrs. Astleys have a very elegant Pavilion, for exhibiting amusements of a similar description, which they have lately erected, and fitted out in a most complete style, in Newcastle street in the Strand, and named Astley’s Pavilion.

At this place the horses have displayed some feats of so wonderful a description, as could not easily be conceived unless they were seen. In this place eight horses have lately performed country dances, &c. in a manner that has astonished all the spectators. To this have been added divers horsemanships, the twelve wonderful voltigers, &c.

The annexed print, which is-

A VIEW OF THE AMPHITHEATRE AT WESTMINSTER BRIDGE,

gives a very good idea of the scene. Mr. Rowlandson’s figures are here, as indeed they invariably are, exact delineations of the sort of company who frequent public spectacles of this description; they are eminently characteristic, and descriptive of the eager attention with which this sort of spectators contemplate the business going forward. Small as the figures are, we can in a degree pronounce upon their rank in life, from the general air and manner with which they are marked.

Mr. Pugin is entitled to equal praise, from the taste which he has displayed in the perspective and general effect of the whole, which renders it altogether an extremely pleasing and interesting little print.

With respect to teaching horses to perform country dances, how far thus accomplishing this animal, renders him either a more happy or a more valuable member of the horse community, is a question which I leave to be discussed by those sapient philosophers, who have so learnedly and so long debated this important business, with respect to man.

The school of Jean Jaques Rousseau, who insist upon it, that man, by his civilization, has been so far from adding to his happiness, that he has increased and multiplied his miseries* will of course insist upon it, that a horse in his natural state must be infinitely happier, than he can be with any improvements introduced by man; that all these artificial refinements must tend to diminish, instead of increasing his felicity; and that, as a horse, he had much better be left in a state of nature, than thus tortured into artificial refinement.

The advocates for Swift’s system of the Houyhnhnms, in Gulliver’s Travels, admitting a horse to be superior to a man, even in his natural state, will unquestionably be of the same opinion ; and we must seek farther for the advantages to be derived by introducing a teacher of dancing, and a master of the ceremonies, to this noble and dignified animal.

It is recorded, that at a much earlier period, a right worshipful mayor of Coventry wished to teach his horse good manners. Queen Elizabeth, in one of her progresses to that city, was met, about a mile before she arrived there, by the mayor and aldermen, who desirous of declaring the high honour which they felt she would thus confer on their city, employed the mayor to be their speaker. The mayor was on horseback, and (as the record saith) the queen was also on horseback, behind one of her courtiers. A little rivulet happening to run across the road where they stopped, the mayor’s horse made several attempts to drink; which the queen observing, told his worship, that before he began his oration, she wished he would let his horse take his draught. “That, an please your majesty, he shall not,” replied the mayor, “that he certainly shall not yet. I would have him to know, that it is proper your majesty’s horse should drink first, — and then, he shall.”