Beaudesert, Staffordshire, from Fragments on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, pub. 1816. Humphry Repton

The Gardenesque: Humphry Repton, John Claudius Loudon

The Picturesque aesthetic was a literary reaction to both the landscape legacy of Capability Brown and Humphry Repton’s ‘Gardenesque‘ of the close of the eighteenth century. First defined by John Claudius Loudon (1783-1843) in 1832, the Gardenesque was a style characteristic of the small-scale turn of the century garden, which emphasised formal features and botanical variety. Repton (1752-1818), a consummate snob, came to garden design relatively late in life, setting himself up as Brown’s successor in 1788. This precarious position brought him nothing but persecution from the Picturesque writers, and he was thrust headlong into their savage debates. Attacks rained down [from William Gilpin, Richard Payne Knight, and Uvedale Price]. There was no unanimous stylistic agreement among these, and yet all three expressed a preference for the diverse terrain of the Rococo garden and a violent dislike of Brown’s manicured landscapes… the Picturesque ideal was deemed an instinctual reaction to ‘rough’, ‘intricate’, or ‘broken’ Nature. It paved the way for a more Romantic appreciation of Gothic architecture and rough-hewn topography.

The Picturesque: William Gilpin, Richard Payne Knight, Uvedale Price

Gilpin himself never owned or designed an actual landscape… Nevertheless, his ideas concerning the beauties of natural scenery underpinned the more complex theoretical arguments of Payne Knight and Price twenty years later. His influential reception was also aided by an established craze for domestic tourism. From the 1780’s, as a result of increasing outbreaks of war in Europe, Continental travel was deemed overly dangerous. Classically orientated tours were therefore abandoned in favour of the safer thrills offered by Britain’s mountains, cascades and cliffs, championed by the promulgators of the Picturesque. By the end of the eighteeneth century, Hoare had been forced to build a hotel at Stourton to accommodate his garden tourists.

The painterly qualities of Sir Rowland and Sir Richard Hill’s Shropshire estate, Hawkstone, and Valentine Morris’s Piercefield in Monmouthshire attracted Picturesque tourists in their hundreds. Hawkstone’s conventional landscape park was laid out in 1784-90 by William Emes. The separate pleasure grounds were arranged around a dramatic ravine of sandstone, complete with a ruinous Red Castle. Dr. Johnson surmised that Hawkstone’s Grotto Hill, with its panoramic views, forced upon the mind: ‘The sublime, the dreadful, and the vast. Above is inaccessible altitude, below, is horrible profundity.’ Piercefield, likewise, commands sandstone cliffs of 300 feet in height. Gilpin, Price and Repton all visited the estate, to marvel at its perilously winding river and steeply wooded bluffs. It was, after all, an established part of the Wye Tour.

Sir Uvedale Price (1747-1829) accused [Capability] Brown of mechanically ‘smoothing and levelling the ground,’ where ‘in a few hours the rash hand of false taste completely demolishes what time only, and a thousand lucky accidents, can mature’. Price criticised the clump, ‘whose name, if the first letter was taken away, would most accurately describe its form and effect’. Picturesque taste equated ‘verdure and smoothness’ with monotony, instead of pronouncing ‘accident and neglect the sources of variety in unimproved parks and forests’. Brown and his followers had taken great care to conceal any roughness prevailing in their landscape parks. As a result, Gilpin railed, ‘How flat, and insipid is often the garden scene, how puerile, how absurd!’

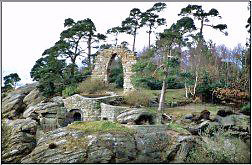

[Knight] argued that the Picturesque defined a journey of aesthetic and emotional discovery, which united all the arts. [Richard] Payne Knight was a wealthy connoisseur and member of the Society of Dilettanti… At Downton, the half-Roman, half-Gothic estate Knight inherited in 1764, he believed he was ‘collecting and cherishing the accidental beauties of wild nature’. The sinister landscape included a hermitage and isolated cold bath. When Repton visited in 1789, he took in the ‘roaring in the dark abyss below’ of the River Teme, which was ‘enriched by caves and cells, hovels, and covered seats, or other buildings, in perfect harmony with the wild but pleasing horrors of the scene’.

Lacking both Brown’s personable, working-class nature and practical grounding in gardening, Repton nevertheless hit upon a winning strategy: the Red Book.

The triumph of these gimmicks, which were printed and found for each individual client between red Moroccan leather covers, was to give posterity an impression of wider landscape improvements than were ever achieved. Essentially, the Red Book was a detailed and persuasive contract for improvements, illustrated with seductive ‘before and after’ snapshots of the estate in question. An overlay allowed the prospective client to picture immediately the possibilities lying dormant within his grounds, should he choose to employ the services of Repton… [W]hen business was slow, Repton reproduced them in albums… Perhaps his most successfully realised Red Book design was for the Blaise Castle estate on the outskirts of Henbury in Bristol for the quaker banker, John Scandrett Harford, in 1795. The result trod a fine line between the ideal parkscape and the wilderness craved by the Picturesque tourist.

Payne Knight had promoted the reinstating of terraced gardens and other landscape features dismantled by Brown and his followers. Although ultimately Repton rejected the notions of the Picturesque, his cluttered compositions of pedestals, pergolas and fountains also drew on the formal gardens of the previous century for inspiration… The shift in emphasis from the park back to the designed garden anticipated the ‘Gardenesque’, as defined by Loudon. Repton’s designs triumphed because of their usefulness and attention to ‘the genius of the place.’ After all most English landscapes did not lend themselves to the Picturesque ideal of mountainous scenery half as easily as they did to the Reptonian concept of an adaptable space on a human scale… The truth was that the average landowner at the turn of the century wanted ‘bowling-greens, flowering shrubs, horse-ponds’, and hankered after the ‘shell-grottoes, & Chinée-rails’ of the Rococo Arcadias.

By 1816, Repton had seemingly turned against the ideal parkscape completely. ‘The Pleasures of a Garden have of late been very much neglected’, he wrote, because of ‘the prevailing custom of placing a House in the middle of a Park, detached from all objects, whether of convenience or magnificence’.