published by Rudolph Ackermann in 3 volumes, 1808–1811.

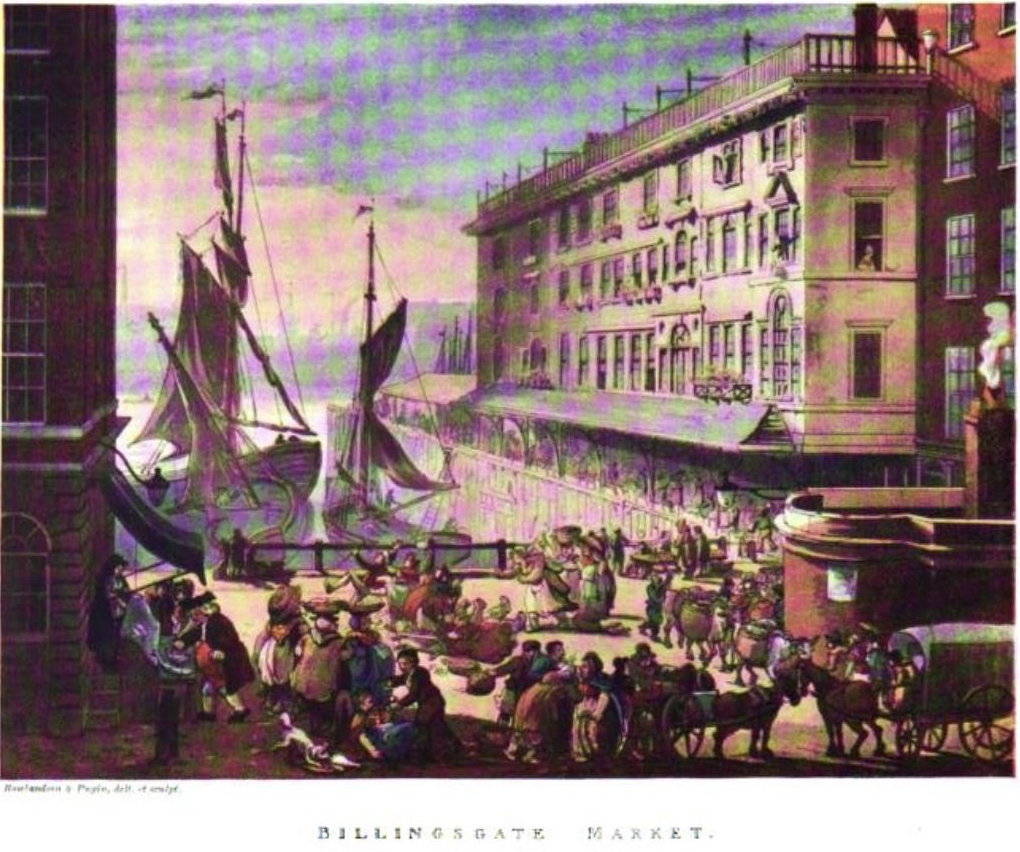

The accompanying print represents, with great humour and animation, a scene in this renowned school of British oratory, an academy from which many illustrious orators, both of the bar and the senate, have derived that energetic and forcible manner, which, in honour of the original seminary, is so emphatically termed Bilingsgate. The power of their eloquence has raised such a tempest and whirlwind of passion in the gentle bosoms of two fair disputants, that, forgetting or laying aside the native softness and delicacy of their sex, they have engaged in furious combat. One of them is just overthrown by her more fortunate adversary, but though fallen, her spirit seems to rise above her fate, and she yet dares the conflict and hopes for victory. Their sister Naiads on either side encourage and foment the immortal strife: one of them has fallen with inconceivable fury on a wretch, who is possibly a Frenchman and a fiddler, and has probably raised this storm by either undervaluing the fair one’s fish, or having made some mal-a-propos observation on its degree of freshness; be this as it may, he seems to be nearly in as bad a situation as Orpheus,

"When, by the rout that made the hideous roar,

His goary visage down the stream was sent,

"Down the swift Hebrus to the Lesbian shore.”

It appears highly probable that the ladies who used poor Orpheus so cruelly, were Grecian Billingsgates; and as they were votaries of Bacchus, and acted under his divine impulse, it seems to strengthen the opinion: certain it is, that the English poissardes are as jealous devotees of the jolly god, as the Grecian Mcenades could be for their lives, and quite as apt to be quarrelsome in their cups: but this point may be left to the learned to settle. In the foreground of this print, one of the ladies is so overcome that she is quite insensible to the kindness of a fisherman, who is entreating her to drink another cup of comfort; she is equally insensible to the robbery a dog is committing on her basket of fish. The old citizen buying a turbot, and the various groups of market people, are delineated with great spirit and fidelity. The buildings are extremely accurate, the perspective easy and natural, and the tout-ensemble interesting and animated.

“Billingsgate, or, to adapt the spelling to the conjectures of antiquaries, who go ‘ beyond the realms of chaos and old night/ Belin’s-gate, or the gate of Belinus, king of Britain, fellow-adventurer with Brennus, king of the Gauls, at the sacking of Rome, three hundred and sixty years before the Christian sera: I submit to the etymology, but must confess there does not appear any record of a gate at this place. His son Lud was more fortunate, for Ludgate preserves his memory to every citizen who knows the just value of antiquity. Gate here signifies only a place where there was a concourse of people*, a common quay or wharf, where there is a free going in and out of the same*. This was a small port for the reception of shipping, and for a considerable time the most important place for the landing of almost every article of commerce. It was not till the reign of William III. that it became celebrated as a fish-market; he, in 1699, by act of Parliament, made it a free port for fish. This act also settled the tolls and duties to be taken, appoints a fine of 20/. to be levied on any fishmonger convicted of engrossing, and permits the sale of mackarel on Sundays. The practice of engrossing and regrating still increasing, it was thought necessary, by an order of the lord mayor, 1707, to endeavour to remedy this abuse. The order states, that, Whereas in and by an act of Parliament made in the tenth and eleventh years of the reign of King William III. entitled “An act to make Billingsgate a free market for fish, &c. it was provided, that any person might buy or sell any kind of fish in the said market, and sell them again in any other market by retail. But the fishmongers bought up the cargoes of the fishermen, and sold them again in the same market, which considerably enhanced the price to the consumer: it was therefore ordered, that no fishmonger, or other person, should sell, or expose to sale, any fish at Billingsgate market; only fishermen, their wives, apprentices, or servants, were to be permitted to sell in the market by retail, that the citizens might have the fish at first hand, according to the true meaning of the law. It was ordered also, that the hours for the fish-market should be, from Lady-day to Michaelmas, at four o’clock in the morning, and from Michaelmas to Lady-day, at six o’clock; that none presume to buy or sell any fish before those hours, except herrings, sprats, mackarel, and shell-fish, on pain of being proceeded against as forestalled of the market. Notice of the opening of the market is given by the ringing of a bell; the market continues open till twelve o’clock, when the business closes for two hours, after which it again commences, and continues till five in the evening. The whole is under the jurisdiction of the lord mayor and court of aldermen. A clerk of the market attends to receive the tolls, &c.; and he has authority to order, that all the fish brought into the port shall be sold in the market, and all fish that he shall deem putrid and unwholesome, by his order must be destroyed. The business of the market is now conducted by salesmen, to whom the cargoes of the boats are consigned by the owners; great quantities of fish are also brought from the coast by land carriage. About fourteen or fifteen years since, commenced the practice of bringing fresh salmon from Newcastle and Berwick, enclosed in boxes of ice, by which excellent contrivance the inhabitants of London are supplied with that fish extremely reasonable and in the greatest perfection.

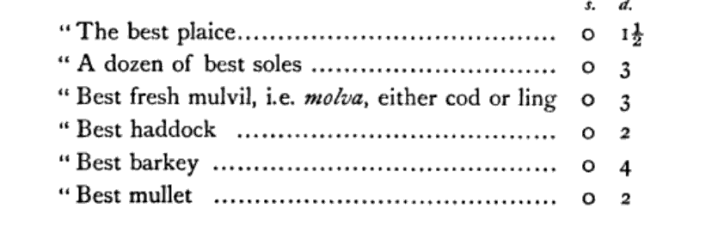

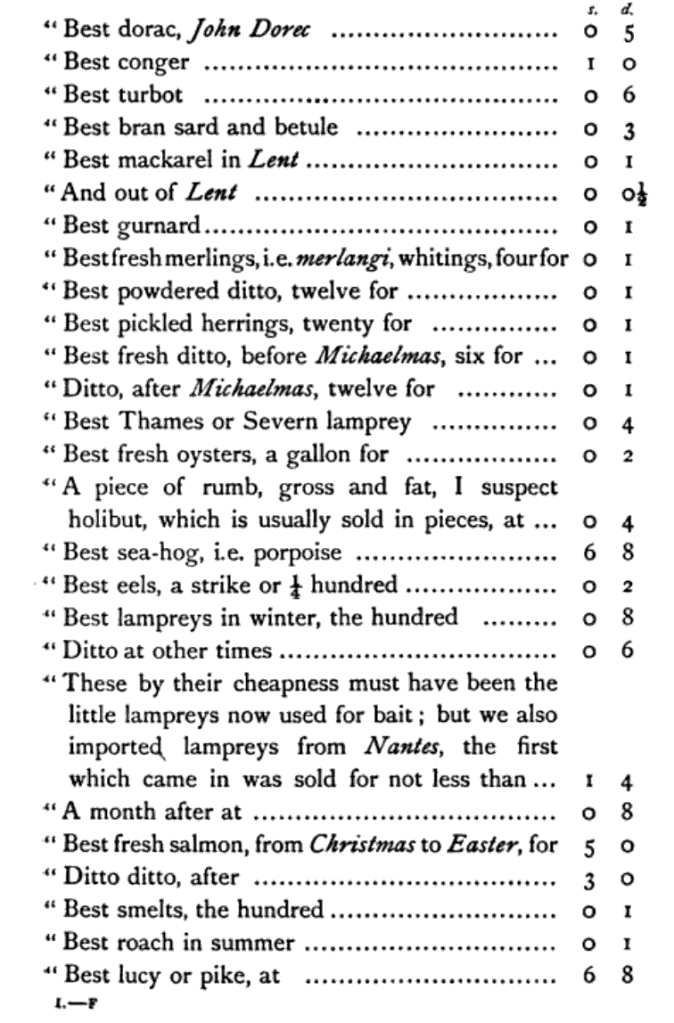

Pennant gives a curious list of the fish brought to market in the reign of Edward I. who descended even to regulate the prices.

“Among these fish, let me observe the conger is at present never admitted to any good table; and to speak of serving up a porpoise whole, or in part, would set your guests a-staring; yet such is the difference of taste, that both these fish were in high esteem. King Richard’s master cooks have left a most excellent receipt for congur in sawsc*; and as for the other great fish, it was either to be eaten roasted or salted, or in broth, or furmente with porpesse. The learned Doctor Caius even tells us the proper sauce, and says, that it should be the same with that for a dolphin; another dish unheard of in our days. From the great price the lucy or pike bore, one may reasonably suspect it was at that time an exotic fish, and brought over at a vast expence. To this list of sea-fish, which were in those days admitted to table, may be added the sturgeon and ling; and there is twice mention, in Archbishop Nevill’s great feast, of a certain fish, both roasted and baked, unknown at present, called a thirl-poole.”

* Skinner’s Etymology.

* Edward the First’s grant of Botolph’s quay.

* Forme of cury.