Amusements of Old London

William B. Boulton, 1901

“… an attempt to survey the amusements of Londoners during a period which began… with the Restoration of King Charles the Second and ended with the accession of Her Majesty Queen Victoria.”

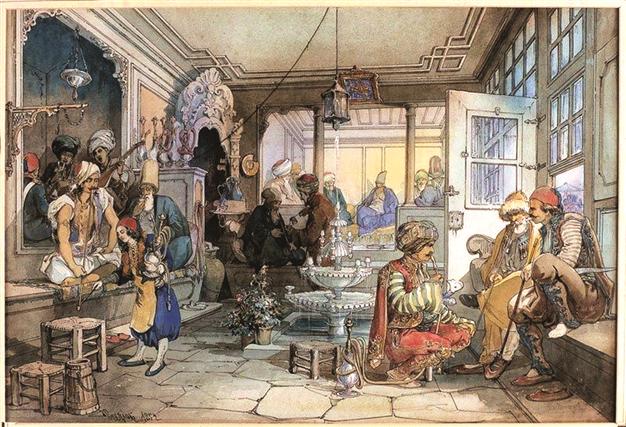

The origin of the gentleman’s club can be traced to the introduction of “the bitter black drink called coffee,” as described by Samuel Pepys, during the last years of William III. Boulton points to “a humble establishment which was opened for the sale of coffee in St. Michael’s Alley, Cornhill, in the year 1652, as the parent of institutions of such superfine male fashion as White’s, the Turf, or the Marlborough Clubs of our day.”

Mr. Edwards, a Turkey merchant, who was accustomed to travel in the East, acquired the Oriental habit on his travels, and brought home with him to London from Ragusa… a youth who acted as his servant and was accustomed to prepare Mr. Edwards’ coffee for him of a morning. “But the novelty thereof,” says Mr. Oldys the antiquarian, “drawing too much company to him he allowed the said servant with another of his son-in-law to set up the first coffee-house in London at St. Michael’s Alley in Cornhill.

By the beginning of the eighteenth century the coffee-houses in the town were so increased in numbers that they were reckoned at 3000 by Mr. Hatton in his “New View of London,” and the coffee-house had already taken its place as one of the most remarkable among the social developments of modern England.

For by the time that Queen Anne came to the throne all London had arranged itself into groups of patrons for one or other of the different coffee-houses. City merchants went to Garraway’s in Change Alley, Cornhill, a house which combined business with pleasure, and had an auction-room on the first floor… Much of the gambling in connection with the South Sea Bubble of 1720 was conducted at Garraway’s. Jonathan’s, also in Change Alley, was another famous house of business devoted to stock-jobbers. Lloyd’s, the great organisation of the shipping interest… is the development of a coffee-house of the same name… The doctors had their meeting-house at Batson’s at the Royal Exchange, where physicians used to meet the apothecaries and prescribe for patients they were neer to see. The clergy, from bishops downwards, went to Child’s in St. Paul’s Churchyard or the Chapter Coffee-house in Paternoster Row. Leaving the city and proceeding westward, Nando’s, the house at Temple Bar…; Dick’s…; Serle’s…; the Grecian…; and Squire’s… were all houses near the various Inns of Court and were much haunted by lawyers.

Then there were the coffee-houses for men of a certain intellectual interest. “The great Dryden” held court at Wills’s, on the corner of Bow and Russell Streets. Dean Swift, along with Mr. Addison and Mr. Steele, took over the literary tradition after Dryden’s death at Button’s, on the other side of Russell Street. The Bedford in Covent Garden was the haunt of Foote, Fielding, Churchill, Hogarth, Dr. Arne, and Goldsmith.

Further west still can be found the birthplace of the social club, those clubs

supported by lounging men of fashion, the “pretty fellows” of Anne and the Georges, and by the adventurers and sycophants who had fortunes to push in such fine company. The most fashionable of these houses were clustered in or near the parish of St. James’s, taking their tone, as was natural, from the neighbourhood of the court. Many of these places had a political cast, but all were meeting-places of men of birth and condition.

The St. James coffee-house was primarily Whig. The Cocoa Tree at Pall Mall “gathered the Tories and those discontented gentlemen who looked askance at the Hanoverian king at St. James’s, and drank furtive healths to the Pretender.” White’s Chocolate House (the true origin the social club) “was a meeting place for the more fashionable exquisites of the town and the court, and for the followers who lived upon them.

Mr. Mackay describes the coffee-houses in “Journey Through England” (1714).

About twelve o’clock, the beau monde assemble in several coffee and chocolate houses, the best of which are White’s Chocolate-house, the Cocoa Tree, the Smyrna, and the British coffee-houses, and all these so near one another, that in less than hour you see the company of them all. You are entertained at piquet or basset at White’s, or you may talk politics at the Smyrna or St. James’s,”

Tea, coffee, and chocolate, and wine were purveyed at these houses, with light viands like biscuit and sandwiches; set meals were supplied only at the taverns—houses of a different type in which… the sale of liquor was the chief object. “But the general way here,” says Mr. Mackay, “is to make a party at the coffee-house to go to dine at the tavern, except you are invited to dine at the table of some great man.”

Boulton suggests that the development of the coffee-houses was

the expression of a feeling of security among all classes of Englishmen after the troubled days of the seventeenth century… Men now for the first time for a hundred years saw opportunities both for business and relaxation which had been impossible during the period of civil and religious tumult… which was only attained by the Act of Settlement and by the acceptance of the Hanoverian dynasty. A period of social prosperity and expansion was then beginning which leveloped later under the wise rule of the sagacious Walpole, and made possible amenities of social life which had been unknown in England since the days of Elizabeth.

The Kit Kat Club was “the very expression itself of the security and beneficence of the new order of things under the wise Whig rule.

Dean Swift, who organized the Brothers Club, stated that “the end of our club is to advance conversation and friendship, and to reward learning without interest or recommendation.”

The Royal Society and the Dilettante Society were the two clubs devoted to scholarship as well as social intercourse. Notable members of the latter were Reynolds, Fitzwilliam, Charles Fox, Garrick, Colman, and Windham, but not Horace Walpole, who failed to be admitted and was fond of saying that “the nominal qualification is having been to Italy, and the real one being drunk.”

The tradition of the Sublime Society of Beefsteaks, which included such men as William Hogarth, Francis Hayman, Churchill, Mr. Wilkes, Lord Sandwich, Mr. Garrick, Mr. Chase Price, and the Prince of Wales, was “nothing more than the joviality arising from these meetings to eat beefsteak and drink port wine, the only viands allowed by its rules.”

The Literary Club was “[t]he most notable… of all these famous gatherings which were the solace of the leisure of men of distinction throughout the eighteenth century.” That choice society was so exlusive that it blackballed bishops and Lord Chancellors, and kept its own friends waiting for years for admission to its charmed circle because they expressed too much confidence of joining.

White’s Chocolate-house

Founded in 1693 by a man called Francis White, White’s was the parent of the English social club. It was here where gaming became fashionable, “Mr. Heidegger issued his tickets for the masquerade,” and where lost things, such as a sword or a lady’s lapdog, were returned in exchange for a reward.

“The club, in its origin, was aristocratic, a lounging-place for the leisure of a lazy society.” But its reputation for nearly a century was as a location for serious gaming. The Earl of Orford called it “the bane of half the English aristocracy.”

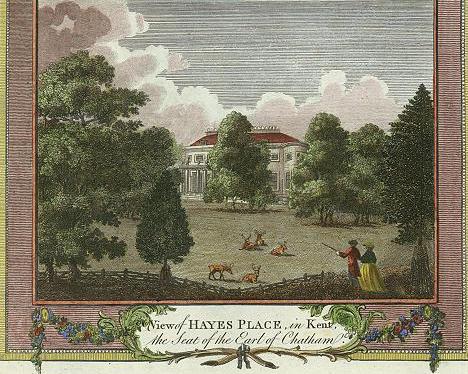

Although it was “the club of the great noble, of the courtier and the statesman,” it wasn’t known for politics. Members included Sir Robert Walpole and William Pulteney, William Pitt and Henry Fox, Charles James Fox, and representatives from “most of the great families of that day, Russells, Churchills, Pelhams, Stanhopes, Herveys, and Cavendishes.”

Social distinction, in fact, was the chief qualification for membership… and its pretensions as an appanage of the aristocracy were never better described than by Horace Walpole, who declared that when an heir was born to a great house, the butler went first to White’s to enter his name in the candidates’ book, and then on to the registry office to record the birth.

White’s was the only club, according to Boulton, until Almack’s and Boodle’s came into to existence in the time of George III.

Member elections at White’s occurred so seldom that in 1743, certain gentlemen with aspirations to join started a second club, in its own rooms, calling itself “The Young Club at White’s (the first one thus becoming known as the “Old Club.”

The elders seem to have looked upon the junior concern with a mild and benevolent eye, and although, as we say, quite separate, with rules and a cook of its own, the Young Club at White’s was ultimately accepted by those potentates as a place of purgatory or probation, where the young man might, by the blessing of Providence, become purged from all contamination of intercourse with ordinary people, and worthy of communion with their own charmed circle.

Occasionally a candidate for the Old Club passed quickly from the Young Club, but he was invariably a man of parts and possessed of great influence; young Mr. Charles Fox, for instance, was elected to both clubs at White’s in the same year, owing no doubt to the efforts of his father, Lord Holland, who was a noted member of the Old Club. His friend George Selwyn, on the other hand, waited eight years in the junior concern, and another typical clubman of the same set, Lord March, was consistently rejected year after year, and only joined the old society when the two clubs were merged in the year 1781.

The famous betting-book contains many outrageous wagers such as the time when a man dropped dead in the doorway and the members made wagers as to whether he was alive or dead, but the most common wagers dealt with births, marriages, and deaths among the prominent society members.

On the 4th of November 1754, there was entered… the following wager: “Lord Montfort wagers Sir John Bland one hundred guineas that Mr. Nash outlives Mr. Cibber.” The bet refers, of course, to the aged poet laureate Colley Cibber, and to the equally venerable Beau Nash, for so many years a prominent figure at Bath. Below this entry is the very significant note in another handwriting (quite possibly Horace Walpole’s, who noticed the wager): “Both Lord Montfort and Sir Bland put an end to their own lives before the bet was decided.”

At the ascension to the throne of George III, who openly disapproved of gaming, White’s “became a place of meeting for serious men of affairs, the old gaiety and revel… sadly curtailed under the new dispensation… [A]nd the careless youth of the period began to look out for a place more to their liking.”

Almack’s (now known as Brooks’s)

[T]he origin of Almack’s was, as we say, a revolt of the gay youth of 1764 against the ordered decorum of White’s, and an effort to discover another place of meeting where the old rites of hazard and faro could be continued unmaimed. Almack’s assumed from the outset the greatest pretensions to fashion; the young Dukes of Roxburghe, Richmond, Grafton, and Portland were among its original members, aand its early elections included most of the famous young men about town of those days, Mr. Crewe, Sir Charles Banbury, Richard Fitzpatrick and his brother Lord Ossory, both the young Foxes, their cousin Lord Ilchester…, and the young Lord Carlisle, who seems to have been a typical pigeon of the play tables. A little later came Selwyn and Horry Walpole, Gilly Williams and March…; later still young Mr. Sheridan and the Whigs like Burke, Erskine, and Lord Holland, and the intellectuals like Gibbon, Reynolds, and Garrick; last, but not least, his Royal Highness George Prince of Wales and the Duke of York.

Boulton claims Almack’s (Brooks’s) resembled the earlier White’s, although he says that “play revived at Brooks’s in a splendour which quite surpassed all the early glories at White’s, and was perhaps only equalled by the doings at Crockford’s during the first half of the [nineteenth] century.”

The most prominent member of Brooks’s, and its most reckless gamer, was Mr. Charles James Fox.

Mr. Fox’s first notable efforts in public life had taken the form of rather lighthearted revolts against his header, Lord North, whom he had opposed on such measures as Royal Marriage Bills, and in so doing had deeply offended the king. His Majesty had written to Lord North that he considered “that young man had cast off every principle of honesty,” and the royal scruples were increased fourfold by the reports which reached him of the excesses of wine and hazard at Brooks’s, in which Mr. Fox was the most eminent figure. Worst of all, the Prince of Wales, who was eager from the day he reached manhood to embrace every opportunity of making himself disagreeable to his Majesty, was pleased to humour Mr. Fox with his particular friendship and countenance, and to announce his intention of joining his friend’s favourite club. From that time forward Brooks’s was taboo at court, and party politics were introduced into club life for the first time.

The young Mr. Pitt, when he came into public life, realized that as long as George III was in power, any political effort that included Charles Fox was doomed. Therefore, he chose to join White’s instead, “and as long as those two great personalities remained in public life, the stormy politics of their times raged about the two clubs, and were directed from each.

In the early years of the nineteenth century, gaming-houses sprung up all over the West End, and the attraction of both of these clubs turned to the “extraordinary cult of male fashion” known as the Dandies.

The Dandies

The whole movement was the assumption by a small coterie of men of fashion of a social superiority above their fellows, and the supporting of their pretensions by an arrogance which had been unknown in polite society before their day. The inspiration was supplied by that pattern of fine gentlemen the Prince Regent, at a time of life when the charm of his youth has disappeared, and it was imparted to such among the younger men in St. James’s Street as were found worthy by the incomparable Mr. Brummell.

Boulton finds it unaccountable that a man of middle-class origin who exhibited such rude and obnoxious behavior as he did, could have been made the “male fashion of an entire generation.”

The men who followed Mr. Brummell… made club life at White’s and Brooks’s well-nigh unendurable to any but their own set… Their savage blackballing decimated the club during a period of twenty years, and at least rendered necessary an alteration of rules which placed the ballot in the hands of a committee in order to save the club from extinction.

With White’s and Brooks’s off the list of possibility for most gentlemen of leisure, other clubs were established, such as the Alfred Club, for men of letters, judges, and bishops; the Travellers’ Club, founded by Lord Castlereagh, for men who had travelled “five hundred miles from London in a straight line;” and military and naval clubs, as well as others.