Robert Adam: His Story

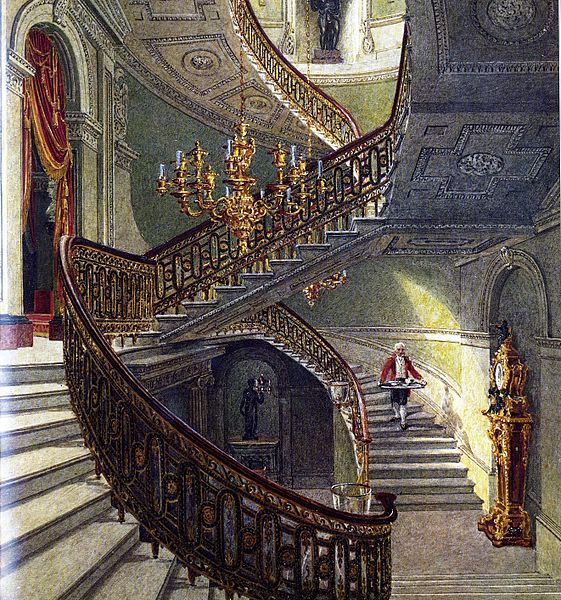

Anyone who follows this blog is probably aware that Robert Adam is my favorite interior designer. I love the elegance, color, and classical design of his ceiling designs most of all. Every year when I visit the UK, I include stately manors featuring his work—and am ever so glad that there are so many of them still around to admire.

The second son of a prominent Scots architect himself—William Adam—Robert grew up with the advantages of money and an expectation that he would follow in his father’s footsteps. As a second son, however, that meant working under his older brother John, which he did for eight years before striking out on his own. Eventually, he was joined by his younger brother James. The youngest brother, William, served both enterprises with his building materials business.

Coming of age at a time when enthusiasm for the traditional Grand Tour was rekindled, Robert (who did not finish his studies at Edinburgh University due to illness) set out for Europe with the Honorable Charles Hope, younger brother of the Earl of Hopetoun. In Florence, the French antiquarian Charles-Louis Clerisseau agreed to instruct him in watercolor and draftsmanship. Rome, where he and Hope separated, was to be Adam’s base for the next three years, where he continued to study under Clerisseau and associated with other British artists and potential patrons, including James Wyatt and Adam’s lifelong rival, William Chambers, whom he identified as a “formidable foe.”

In Rome, Adam was careful not to jeopardize his gentleman’s status by identifying himself as an architect, which would preclude his participation in aristocratic circles. He was acutely aware that as important as it was to developi his artistic skills, it was equally important to develop relationships with the sort of people who might wish to take advantage of them in future endeavors. A “gentleman architect” was a bit of an oxymoron at the time, but Adam was one eventually who managed to achieve it.

Adam devoted himself to making detailed studies of both ancient and Renaissance buildings, particularly the decoration of the Roman vaults known as grotte, which led to the development of a type of ornamentation called “grotesque.” (Which seems an odd designation to me, since his designs are anything but grotesque. But I don’t speak the language of architecture.)

Adam was to achieve “a delicacy of detail…” which was new to England—and indeed to the world, for it was a delicacy by Roman and not Rococo means. The grottesque, painted and stucco decoration in Roman buildings, were his model.

Professor Nikolaus Pevsner (1902-1983)

Adam’s use of colour… was not, as is too often and disastrously thought, a gay “picking-out” of decorative motifs, but a subtle and gentle modification of the traditional white finish which Adam found too glaring in practice. Even the richest schemes are carefully built up from this principle.

Sir John Summerson (1904-1992)

At this time, Adam met Robert Wood, whose illustrated account of the Ruins of Palmyra became a useful sourcebook for architects and designers, and Adam was to eventually draw more from Wood than from his first-hand studies. Adam meant to write his own such book on the baths of Diocletian and Caracalla, but the theorist of the family turned out to be his younger brother James. Robert was more of a doer.

Robert Adam’s criticism was directed against

the slavish imitators of Vitruvius and Palladio in his own century, who reduced the architectural heritage of the ancient world to a set of rigid rules to be dogmatically applied. Adam’s demand, which he believed to be soundly based on the realities of ancient practice, was that the architect should assert the flexibility and freedom proper to a creative artist: ‘The great masters of antiquity were not so rigidly scrupulous. They varied the proportions of the general spirit of their compositions required, clearly perceiving that however necessary these rules may be to form the taste and correct the licentiousness of the scholar, they cramp the genius and circumscribe the ideas of the master.’

This was heresy to eighteenth-century traditionalist architects, but Adam believed that the goal of architecture was not dependent on a set of rigid rules, but the achievement of a fluency and freedom of expression, that in his case meant the “ability to balance simplicity with enrichment.”

“Movement,” a fundamental principle of his work and a recurring motif in his projects, was defined by him with this analogy “…rising and falling, advancing and receding… with convexity and concavity… have the same effect in architecture, that hill and dale, fore-ground and distance, swelling and sinking have in landscape.” Architecture, like landscape, should “aspire to an agreeable and diversified contour, that groups and contrasts like a picture.”

Upon the completion of his Grand Tour, Adam decided to set up his independent practice in London, rather than following the family business in Edinburgh, which was a much less risky proposition. The family wealth was useful in helping him set up a house with six servants in fashionable St. James Place, and later purchase a house in Lower Grosvenor Street. His sisters managed his household and his brothers James and William came along to assist in his endeavors.

Networking was second nature to Adam. He joined the recently established Royal Society of the Arts, but by virtue of birth he already belonged to an informal institution far more powerful than any official association—the club of London Scots. The unofficial head of this ‘tartan mafia’ was John Stuart, third Earl of Bute and tutor to the future king George III. Adam inveigled an introduction…, and, although the initial contact with Bute was brusque almost to the point of insult, he was to gain commissions from him in both town and country. But by the time he did so Adam was already on course to be England’s most fashionable architect.

Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire, was Adam’s first major commission. Adam created the south front and also designed the much of the interior, furniture, and grounds. Although his was somewhat of a partial role—some rooms having been done by others—his work includes the library, saloon, ante-room, dressing room, state bedroom, and dining room. Very few changes have been made in the design, so Kedleston remains a significant example of his work.

At Syon House, in 1761, the first Duke of Northumberland challenged him “to create a palace of Graeco-Roman splendour.” Adam was only too eager to accept the challenge, submitting, as he often did, an overly-ambitious plan that had to be modified. The result, however, included a “sequence of rooms of contrasting geometrical shapes, each originating in a classical prototype.” Lord Norwich claimed that “this spectacular sequence of rooms is enough to earn its creator a lasting place in the Halls of Fame and makes Syon one of the showplaces not just of London but of all England.

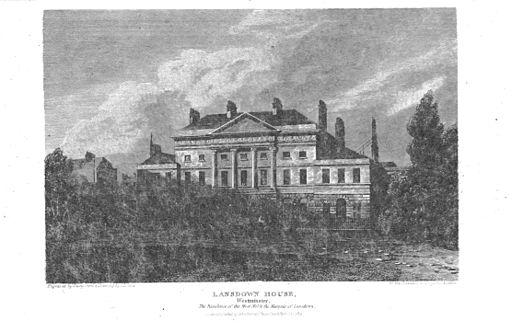

That same year, Adam was commissioned to decorate Osterley Park in Middlesex, owned by the Child banking dynasty. Among his repertoire of projects in the coming years was Ugbrooke, Devon; a gatehouse for Kimbolton Castle, in Cambridgeshire; Bowood, in Wiltshire; Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill at Twickenham; Newby Hall, North Yorkshire; Harewood House, in Yorkshire; Nostell Priory, in Yorkshire; Audley End, in Essex; Saltram, in Devon; Landsdowne House, Kenwood, Chandos House, Home House, Portland Place, Derby House, Home House, Northumberland House, all in London. When Northumberland House was destroyed to make way for Northumberland Avenue, the duke had Adam’s glass drawing-room packed up and stored; it is partially restored in the British Galleries at the Victoria & Albert Museum.

The Adelphi Project, which would turn out to be a major failure that brought his business to the brink of bankruptcy, was conceived to be a “riverside terrace of residences of imperial grandeur… positioned above an arcade of warehouses.” Thinking that they would be besieged by eager tenants, the Adams brothers sank their own money and political power (Robert was an MP for Kinross-shire at the time) into getting this project up and running. Unfortunately, errors in calculations for the positioning of the wharf, as well as other problems, proved disastrous, and the brothers had to sell the property for a pittance, as well as their own private collections of antiquities.

Adam’s obituary in the Gentleman’s Magazine was unequivocal in its judgement—’Mr. Adam produced a total change in the architecture of this country.’ ‘Architecture’ in that context must be understood as an all-embracing term. The papers Adam bequeathed to posterity include designs for organ-cases, sedan-chairs, coach-panels, candlesticks, door-handles, salt-cellars—and over five hundred different fireplaces.

“… the chief merit of the Adam variation of the classical style was its recognition of the ancillary trades and crafts. It had, moreover, the attraction of being economical while retaining the appearance of being costly.”

Sir Albert Richardson (1880-1964)

Robert Adam is buried at Westminster Abbey.

My Pinterest Pages

Note:

Quotes are from Robert Adam, by Richard Tames, 2004, Shire Publications.