Amusements of Old London

William B. Boulton, 1901

“… an attempt to survey the amusements of Londoners during a period which began… with the Restoration of King Charles the Second and ended with the accession of Her Majesty Queen Victoria.”

Hazard & White’s

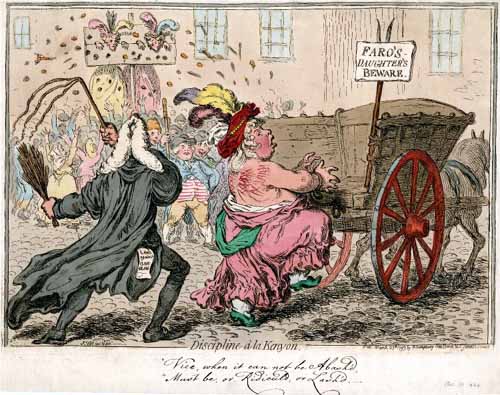

Hazard, the precursor of crap) was a game of pure chance where all players had a fairly equal chance of winning. But as it spread into the lower classes, “organized cheating at low taverns and gaming-houses became a regular profession.” Loaded dice was one way, but there were plenty of other ways. The often violent responses to cheating are illustrated in Rowlandson’s “Kick up at a Hazard Table.”

The game of hazard first became popular in the late 17th century at the coffee-houses, such as (Mrs.) White’s Chocolate House and The Cocoa Tree. Early in the next century, the more fashionable gentlemen at White’s, wishing to avoid the card sharps and other unpleasant types that were inevitably present at these places, formed a more exclusive, private club, “where they could lose fortunes to each other in all privacy and decorum.” Considered by critics to be a “pit of destruction,” White’s saw many fortunes change hands at the turn of a dice.

Young Mr. Harvey of Chigwell, for instance, lost £100,000 to Mr. O’Birne, an Irish gamester. “You can never pay me,” said O’Birne. “Yes, my estate will sell for the money,” was the spirited reply. “No,” said O’Birne, “I will win but ten thousand, and you shall throw for the odd ninety.” They did so and Harvey won, lived to become an admiral, and to fight under Nelson at Trafalgar.

The Georges and Gaming at Court

It was a necessary qualification of a courtier of George the Second to be prepared to sit down with that monarch and the Suffolks and Walmodens and the other picturesque appanages of the court and lose a comfortable sum. Twelfth Night was always a fixture for a sitting of more than ordinary importance at St. James’s. On one of these occasions luck was in favour of Lord Chesterfield, who won so much money that he was afraid to carry it home with him through the streets, and was seen by Queen Caroline from a private window of the palace to trip up the staircase of the Countess of Suffolk’s apartments. He was never in favour at court afterwards.

George III, on the other hand, banished gaming at court and even White’s gambling became quite tame, which is why Almack’s (later Brooks’s) was opened as a venue for serious gamesters, such as Charles James Fox, who was known for playing carelessly “for the excitement alone,” without any concern for the consequences. On one particular day in 1771, after playing hazard for twenty-two hours and losing £11,000, he gave a speech at Westminster, went to White’s and drank until seven in the morning, and then to Almack’s, where he won £6,000, and later in the afternoon took off for Newmarket. A week later, he was back in London and lost £10,000.

Faro

The game of Faro evolved from a game called “basset,” played in the Stuart courts.

Faro was played between the dealer or keeper of the “bank” and the rest of the company, and, like hazard, it gave excitement to as many people as could find room round the table… Each of the company placed his stake upon any card of the thirteen he chose, and when the stakes were all set the dealer took a full pack and dealt it into two heaps, one on his right hand the other on his left, two cards at a time. He paid the stakes placed on such cards as fell on the right-hand pack, and received those of such as fell on his left hand. The dealing of each pair of cards was called a “coup,” and the dealer paid or received such stakes as were decided after each coup… [t]he odds were enormously in favour of the dealer. He claimed all ties, that is, when the same card appeared on both packs, the last card but one of the pack delivered its stake to him upon whichever hand it fell, and there was the impalpable but very real advantage of which was known as the “pull of the table” in his favour.

At Brooks’s, where faro reigned supreme, Charles James Fox and Richard Fitzpatrick (a Whig associate) had a very successful partnership. Lord Robert Spencer’s partnership with Mr. Hare enabled him to win £100,000, whereupon he gave up gambling entirely and purchased an estate in Sussex. “The success of the faro banks at Brooks’s was such that it led to the game being forbidden at White’s by a special rule of the managers.”

Faro, however, was played at many of the great houses and by women of fashion, who would “hire a dealer at five guineas a night to conduct operations, and to suggest that the profits of the table went to him and not to the hostess… to disguise the commercial nature of the transaction…”

Following the 1797 public scandal in the courts where three society ladies were each fined £50 for playing at a public gaming-table—and the popularity of Mr. Gillray’s prints, such as “Pharaoh’s daughters in the pillory and at the cart tail”—the game lost much of its following.

E.O.

E.O., a type of of roulette with a ball and a special table, called roly-poly, from the Continent, found at race meetings, country fairs, and the streets of London, lent itself well to cheating. Colonel O’Kelly, the eventual owner of Eclipse set himself up in business by winning at E.O.

Gaming Houses and the Damage They Caused

Cheap gaming houses all over town featured hazard, roulette, rouge et noir, and macao for small stakes. Frequent raiding did not discourage them, since fines were easily paid.

The mischief these places did is almost incalculable; bankruptcies, embezzlements, duels, and suicides resulting from gaming were of weekly occurrence, and it would seem that half the tradesmen and clerks of London were before the magistrates or the coroners of the last years of [the 18th] century and the first quarter of [the 19th].

Hazard and faro had gone out of the older clubs, and club gaming of the [early 19th century] was represented by extremely deep play at whist at White’s and Brook’s. Macao flourished for a while at Wattiers, where the members lived on each other for some eight or ten years until their estates disappeared and the club expired by the flight of its supporters to Boulogne.

Such were the houses in which round games flourished after their decline at the great clubs. They steadily drained the pockets of the aristocracy of England for nearly half a century, and there is scarcely a great family to-day which does not still feel the effects of the play that went on within their doors sixty years ago.

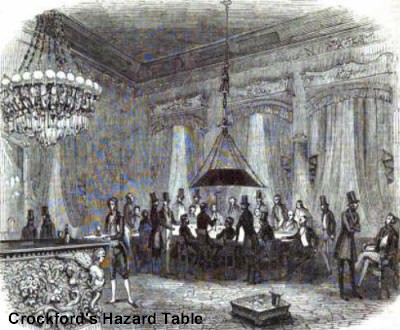

Crockford’s Club

William Crockford, a fishmonger who had a shop in the Strand near Temple Bar, made a killing on a turf transaction and rose from partnerships in shady gaming establishments to spending £94,000 to open his own fashionable club, Crockford’s Club, in 1827.

William Crockford, a fishmonger who had a shop in the Strand near Temple Bar, made a killing on a turf transaction and rose from partnerships in shady gaming establishments to spending £94,000 to open his own fashionable club, Crockford’s Club, in 1827.

There is one thing, and one only, to be said in favour of Mr. Crockford’s enterprise, which, is that this establishment did away with the practice of gentlemen playing against each other for large sums. At Crockford’s, the game was one of Gentlemen versus Players, the players being always Mr. Crockford’s officials at the French hazard table, and the sole object of his business was to win the money of his patrons.

A committee of gentlemen was given charge of accepting and rejecting members, with the effect of making “entry to Crockford’s as difficult as to White’s or Brooks’s.” The price of subscription to Crockford’s establishment was low, but “in exchange for the princely accommodation of his house, and such fare as was unobtainable at any other club, Crockford asked for nothing in return that gentlemen should condescend to take a cast at his table at French hazard.” This incarnation of the old game required a fee called “box money” and “the pull of the table” that went directly into the coffers of the house.

The men who walked into Crockford’s with their eyes open to encounter these odds were the pick of the society of the day, the men who had fought the battles of the country under Wellington, and men who were making great reputations at Westminster, as well as mere butterflies like the Dandies who loafed through life at White’s. They were most of them men of exceptional parts, and distinguished for shrewdness and ability in one walk of life or another, and yet in the short space of ten years, between the opening of the club in 1827 and the succession of her Majesty, their losses converted Mr. Crockford into a millionaire at least. There is absolutely no record of any considerable sum of money ever won at the place by a player.

The second Earl of Sefton lost £200,000 in his lifetime. His son, after paying off the debt, lost another £40,000. Sir Godfrey Webster lost £50,000 at a sitting. Other losers of enormous sums: Lord Rivers, Lord Chesterfield, Lord Anglesey, Lord D’Orsay.

Even before the Gaming Act of 1845, Crockford, having pretty much won all the money to be won, started consolidating and concealing his assets with a view toward retirement. When called to give evidence, he claimed that increasing age caused him to give over the management to the committee of gentlemen tasked with running the membership of the club.

“High play in England, as we believe, burnt itself out in those orgies at Crockford’s.”

The Scandal at Graham’s Club

Another reason for the decline of serious gaming in England was the cheating scandal at Graham’s Club in St. James’s Street.

…a man of an old and honoured name was detected cheating at whist, and was denounced as a dishonest trickster in a newspaper, the Satirist. He brought an action against his accusers, failed in it, went abroad, and died… the details of the trial disclosed ugly features in the circumstances which had much interest for thoughtful people, and undoubtedly tended to bring the whole institution of play for high stakes between gentlemen into great disrepute.

Witnesses at the trial testified that they had witnessed him cheating in any number of ways a hundred times and more, and not only did not turn him in, but continued to sit down with him to play at private clubs. Undoubtedly, many of them were cheating themselves, and thus had no wish to have their play scrutinized. Packs of his marked cards were produced in court. His hacking cough, which always resulted in producing a king of trump, became known as “—’s king cough.”

Since those days of Crockford’s and Graham’s and the Gaming Act, high play has ceased to be any considerable part of the social life of London at clubs or elsewhere.

The Gaming Act of 1845

made a wager unenforceable as a legal contract and stood as law, though amended, until 2007.