Romance of London: Strange Stories, Scenes And Remarkable Person of the Great Town in 3 Volumes

John Timbs

John Timbs (1801-1875), who also wrote as Horace Welby, was an English author and aficionado of antiquities. Born in Clerkenwell, London, he was apprenticed at 16 to a druggist and printer, where he soon showed great literary promise. At 19, he began to write for Monthly Magazine, and a year later he was made secretary to the magazine’s proprietor and there began his career as a writer, editor, and antiquarian.

This particular book is available at googlebooks for free in ebook form. Or you can pay for a print version.

About the Churchills

John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, was a great military hero who reaped many honors and financial rewards from his service to five English monarchs. His wife Sarah was an intimate friend of Queen Anne… until Sarah’s hot temper and conceit earned her dismissal from court. For more about Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, check out this article in Wikipedia.

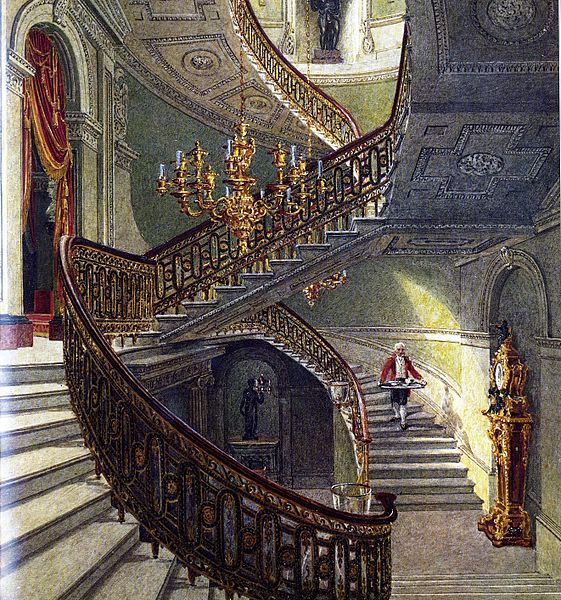

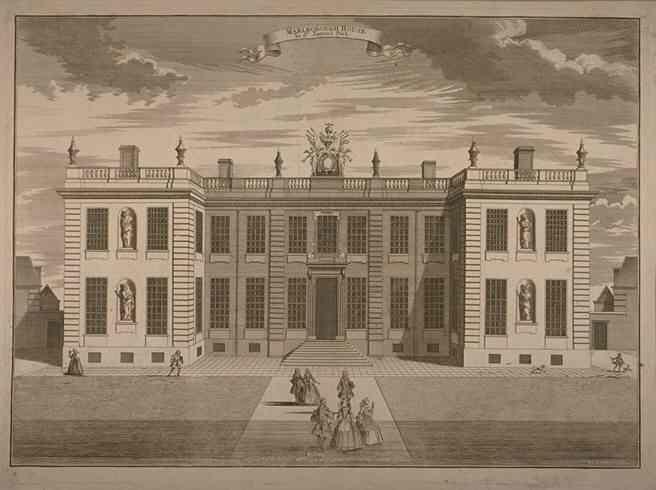

Marlborough House

Little can be said, architecturally, of Marlborough House, notwithstanding it was designed by Sir Christopher Wren, who was employed, not because he was preferred, but that Vanbrugh might be vexed. Respecting Marlborough House, Pennant says

To the east of St. James’s Palace, in the reign of Queen Anne, was built Marlborough House, at the expense of the public. It appears by one of the views of St. James’s, published before the existence of this house, that it was built in part of the Royal Gardens, granted for that purpose by her Majesty. The present Duke [Pennant writes in 1793] added an upper story, and improved the ground floor, which originally wanted a great room. This national compliment cost no less than 40,000l.

As regards the site, Pennant’s account is corroborated by other authorities, who say that the mansion of the famous John Churchill was built on ground “which had been used for keeping pheasants, guinea-hens, partridges, and other fowl, and on that piece of ground taken out of St. James’s Park, then in possession of Henry Boyle, one of her Majesty’s principal Secretaries of State.”

The Duchess both experienced and caused great mortifications here. She used to speak of the King in the adjacent palace as her “neighbor George.” The entrance to the house from Pall Mall was, as it still is, a crooked and inconvenient one. To remedy this defect, she intended to purchase some houses… for the purpose of pulling them down and constructing a more commodious entry to the mansion; but Sir Robert Walpole [whom she considered to be her greatest enemy], with no more dignified motive than mere spite, secured the houses and ground, and erected buildings [there], which… blocked in the front of the Duchess’ mansion. She was subjected to a more temporary, but as inconvenient blockade, when the preparations for the wedding of the imperious Princess Anne [does Timbs mean Mary?] and her ugly husband, the Prince of Orange, was going on. Among other preparations, a boarded gallery, through which the nuptial procession was to pass, was built up close against the Duchess’ windows, completely darkening her rooms. As the boards remained there during the postponement of the ceremony, the Duchess used to look at them with the remark, “I wish the Princess would oblige me by taking away her ‘orange chest!'”*

Note: Currently the home of the Commonwealth Secretariat, the house is usually open to the public for Open House Weekend each September.

The Character of the Duchess

From the Memoirs of Mrs. Delany:

The conversation turned upon the famous Duchess of Marlborough: among others, one striking anecdote, that though she appeared affected in the highest degree at the death of her grand-daughter, the Duchess of Bedford, she sent the day after she died for the jewels she had given her, saying ‘she had only lent them;’ the answer was that she ‘had said she would never demand those jewels again except she danced at court;‘ her answer was ‘then she would be —- if she would not dance at court,’ &c. … She used to say that she was very certain she should go to heaven, and as her ambition went even beyond the grave, that she knew she should have one of the highest seats.

A few of the Duchess’ eccentricities and extravagancies have been put together somewhat in the humorous manner of our early story-books, as follows:

This is the woman who wrote the characters of her contemporaries with a pen dipped in gall and wormwood. This is the Duchess who gave 10,000l to Mr. Pitt for his noble defense of the constitution of his country! … This is the Duchess who, in her old age, used to feign asleep after dinner, and say bitter things at table pat and appropriate, but as if she was not aware of what was going on! This is the lady who drew that beautiful distinction that it was wrong to wish Sir Robert Walpole dead, but only common justice to wish him well hanged. This is the Duchess who tumbled her thoughts out as they arose, and wrote like the wife of the Great Duke Marlborough. This is the lady who quarreled with a wit upon paper (Sir John Vanbrugh), and actually got the better of him in the long run; who shut out the architect of Blenheim from seeing his own edifice, and made him dangle his time away at an inn while his friends were shown the house of the eccentric Sarah.

This is the Duchess who, ever proud and ever malignant, was persuaded to offer her favorite grand-daughter, Lady Diana Spencer, afterwards Duchess of Bedford, to the Prince of Wales, with a fortune of a hundred thousand pounds. He accepted the proposal and the day was fixed for their being secretly married at the Duchess’ Lodge, in the Great Park, at Windsor. Sir Robert Walpole got intelligence of the project, prevented it, and the secret was buried in silence.

This is the Duchess—The wisest fool much time has ever made—who refused the proffered hand of the proud Duke of Somerset, for the sole and sufficient reason that no one should share her heart with the great Duke of Marlborough.

This is the illustrious lady who superintended the building of Blenheim, examined contracts and tenders, talked with carpenters and masons, and thinking sevenpence-halfpenny a bushel for lime too much by a farthing, waged a war to the knife on so small a matter.

This is the celebrated Sarah, who, at the age of eighty-four, when she was told she must either submit to be blistered or die, exclaimed in anger, and with a start in bed, “I won’t be blistered, and I won’t die!”

The Duchess died, notwithstanding what she said, at Marlborough House, in 1774.

*Dr. Doran’s Queens of England—House of Hanover

Romance of London Series

- Romance of London: The Lord Mayor’s Fool… and a Dessert

- Romance of London: Carlton House and the Regency

- Romance of London: The Championship at George IV’s Coronation

- Romance of London: Mrs. Cornelys at Carlisle House

- Romance of London: The Bottle Conjuror

- Romance of London: Bartholomew Fair

- Romance of London: The May Fair and the Strong Woman

- Romance of London: Nancy Dawson, the Hornpipe Dancer

- Romance of London: Milkmaids on May-Day

- Romance of London: Lord Stowell’s Love of Sight-seeing

- Romance of London: The Mermaid Hoax

- Romance of London: The Bluestocking and the Sweeps’ Holiday

- Romance of London: Comments on Hogarth’s “Industries and Idle Apprentices”

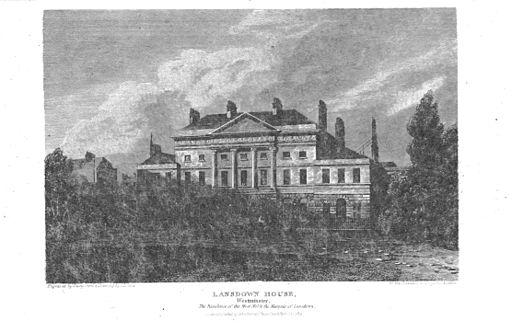

- Romance of London: The Lansdowne Family

- Romance of London: St. Margaret’s Painted Window at Westminster

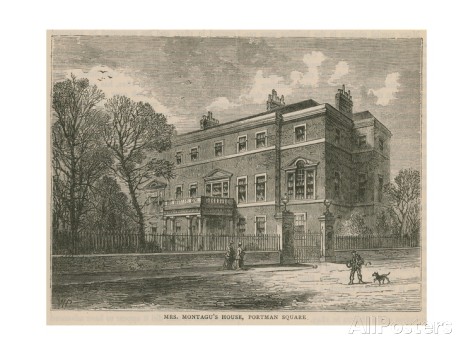

- Romance of London: Montague House and the British Museum

- Romance of London: The Bursting of the South Sea Bubble

- Romance of London: The Thames Tunnel

- Romance of London: Sir William Petty and the Lansdowne Family

- Romance of London: Marlborough House and Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough

- Romance of London: The Duke of Newcastle’s Eccentricities

- Romance of London: Voltaire in London

- Romance of London: The Crossing Sweeper

- Romance of London: Nathan Mayer Rothschild’s Fear of Assassination

- Romance of London: Samuel Rogers, the Banker Poet

- Romance of London: The Eccentricities of Lord Byron

- Romance of London: A London Recluse

![By Isaac Cruikshank (publisher- Willm. Holland, London) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://susanaellisauthor.blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/by-isaac-cruikshank-publisher-willm-holland-london-public-domain-via-wikimedia-commons.png?w=714)