Amusements of Old London

William B. Boulton, 1901

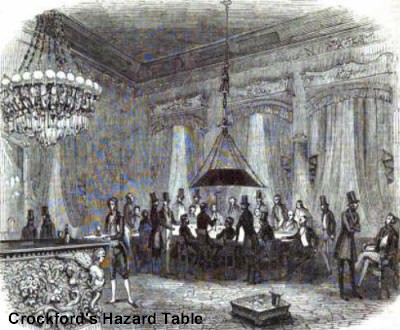

“… an attempt to survey the amusements of Londoners during a period which began… with the Restoration of King Charles the Second and ended with the accession of Her Majesty Queen Victoria.”

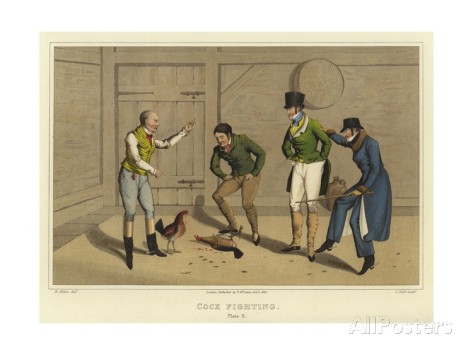

Cock-fighting is recorded as the diversion of ingenious schoolboys by Fitz-Stephen in the reign of Henry the Second… it was prohibited by Edward the Third… it was encouraged by Henry the Eighth, who built the first royal cockpit at Whitehall… it was so much the vogue in high circles in the reign of Charles the First that Vandyck painted a picture of the court watching a match in the royal pit… Oliver Cromwell quite naturally suppressed the diversion by an Act of 1654… and… all its ancient glories were revived by the joyful restoration of King Charles the Second. Modern England, as we contend, began with the days of that monarch, or soon after; we propose therefore to confine our survey of the sport to the days of his Majesty, and since.

Mr. Pepys’s cockpit experience (December 21, 1663)

Being directed by sight of bills upon the walls, I did go to Shoe Lane to see a cock-fight at a new pit there, a sport I never was at in my life. But, Lord, to see the strange variety of people—from Parliament man…to the poorest ‘prentices, bakers, brewers, butchers, draymen, and what not—and all these fellows one with another in swearing, cursing, and betting, and yet I would not but have seen it once. I soon had enough of it, it being strange to observe the nature of these poor creatures; how they will fight till they drop down dead upon the table and strike after they are ready to give up the ghost, not offering to run away when they are wearing or wounded past doing further, whereas when a dunghill brood comes, he will, after a sharp stroke that pricks him, run off the stage, and they wring off his neck without much more ado. Whereas the other they preserve, though their eyes be both out, for breed only of a true cock of the game. Sometimes a cock that has had ten to one against him will be chance give an unlucky blow, and it will strike the other stark dead in a moment, that he never stirs more; but the common rule is that though a cock neither runs nor dies, yet if any man will bet £10 to a crown, and nobody take the bet, the game is given over, and not sooner. One thing more, it is strange to see how people of this poor rank, that look as if they had not bread to put in their mouths, shall bet three or four pounds at one bet and lose it, and yet bet as much the next battle (so they call every match of two cocks), so that one of them will lose £10 or £20 at a meeting; thence having had enough of it.

Cock-fighting

The sport of cock-fighting was not something that could be taken up by just anyone. The requisite breeding and training of the birds for at least two years prior to any matches required a great deal of money, as well as time and attention. But it could be very lucrative also, since the owners received the benefit of portions of the gate-money provided by the spectators.

Numerous books and treatises were written on the manner of breeding and training cocks, including how to choose them when small, how to feed them, and how to set them to spar with each other.

For a sparring match they covered “the cocks’ heels with a pair of hots made of bombasted leather,” that is, they improvised a sort of boxing-gloves for these interesting birds.

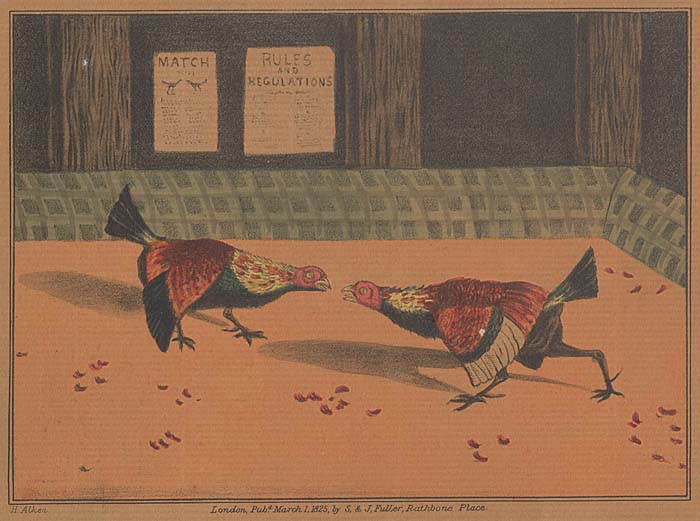

Prior to a match, the cock was trimmed for the fight, “his tail cut into the shape of a short fan… [and] his pinions… trimmed feather by feather, each quill being cut at a slant in order that in rising a lucky stroke might take out the eye of his adversary. Finally, his legs were furnished with the deadly ‘gaffles’ or spurs… some two inches in length, and curved like a surgeon’s needle… either of steel or a silver alloy.”

Birds were matched according to weight, those of middle weight (3-1/2 – 4-1/2 lbs.) being preferred for important venues such as the Royal Cockpit.

As you might imagine, this type of undertaking was not for any but the very rich. Poorer men, however, could and did enjoy the sport as spectators.

Three Orders

The Long Main—those between cities or countries—provided a full week of entertainment, since the time and expense of traveling made it impractical for an event of short duration.

The Short Main lasted a couple of days or even a few hours, and was much infiltrated by amateurs.

The Welch Main was fought for a prize of some sort—”a purse, a gold cup, a fat hog, or some other prize.” The Welch main was rather like a violent dodgeball tournament, something like the Hunger Games. Thirty-two cocks

…were arranged in sixteen pairs, and each couple fought to the death. The winners, or such as survived, were again matched in pairs, and the battle renewed. The eight winners of this second contest provided four pairs for the third; the survivors of the third contest made a couple of pairs for the penultimate combat; and the final issue of the Welch Main lay between this pair of devoted fowl, from which the much-enduring winner of the whole contest emerged… Its opportunities for betting were no greater certainly than in the Long Main… but it had great attractions for the choice spirits of the cockpit…

The Battle Royal, another variation, was simply a bloodbath of any number of birds in the pit, with the last survivor being the winner.

The determination shown by the finest cocks was astonishing. It is no exaggeration to say that the best cocks of the game would show fight as long as a spark of life remained in their devoted bodies. They might be maimed and even blinded, but when confronted by their enemy they would concentrate what little vitality was left to them in the menacing ruffling of their hackles and an expiring peck. This was so well understood that a blinded cock was never declared beaten until his beak was rubbed against that of his adversary.

A somewhat secretive endeavor

It was probably due to its gory nature and the presence of “rough” company that caused aficionados of the “sport” to keep a low profile. Boulton suggests that it was never a particularly popular support among the fashionable men of St. James’s, since there is only one entry in an entire century mentioning cock-fighting in the betting-book at White’s. The Earl of Derby and the Earl of Sefton were known to be supporters, as well as “the families of Warburton, Wilbrahams, Egertons, and Cholmondeleys” and “Lord Mexborough, the Cottons and the Meynells, Admiral Rous, Lord Chesterfield, and General Peel.”

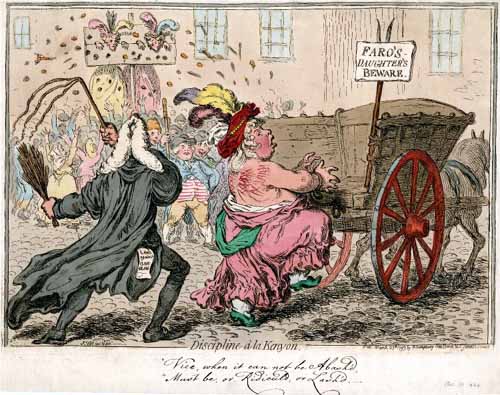

A continuous outcry

Protests about its cruelty were commonplace, as you can see by this satirical advertisement:

“This is to give notice to all lovers of cruelty and promoters of misery, that at the George Inn, on Wednesday, in the Whitsun week, will be provided for their diversion the savage sport of cock-fighting, which cannot but give delight to every breast divested of humanity, and for music, oaths and curses will not fail to resound round the pit, so that this pastime must be greatly approved by such as have no reverence for the Deity nor benevolence for His creatures.”

The Gloucester Journal, 1756

The Cruelty to Animals Act of 1835

This Act amended existing legislation to include (as ‘cattle’) bulls, dogs, bears, goats and sheep, to prohibit bear-baiting and cockfighting, which facilitated further legislation to protect animals, create shelters, veterinary hospitals and more humane transportation and slaughter.

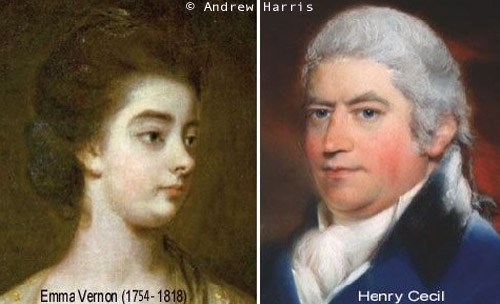

In spite of this legislation cock-fighting did not expire without a struggle. There is an account of [a secretive meeting] in the interesting but rambling memoirs of the Honourable Grantley Berkeley, showing how the Count de Salis, a magistrate, lent his premises near Cranford to Berkeley and his friends for the purpose, gave him the keys of the whole place, and then called in the police and hauled Berkeley before the Bench at Uxbridge. There was much fun excited by the non-appearance of the count, “the cock who would not fight,” and Berkeley was fined five pounds.