Every novel contains, or should contain, certain scenes that stick in the reader’s memory long after the book is finished. The definitive scene in my newest release, Too Hot to Handel, finds Bow Street Runner John Pickett and his Lady Fieldhurst escaping a burning Drury Lane Theatre. This is the only book I’ve ever written that is centered upon an actual event; the Theatre Royal at Drury Lane really did burn down on 24 February, 1809. So, how much was real, and how much is the product of my imagination? Let’s take a look.

First of all, theatre fires were not a rare, or even a new, phenomenon. They had been regular occurrences since the theatres reopened after the Restoration of Charles II. Before that time, fire hadn’t been much of an issue. The theatres of ancient times had been outdoor affairs, and plays had been staged during the daytime. Even Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, although enclosed all around, had a roof that was largely open to the sky, in order to reduce as much as possible the need for artificial lighting. But advances in theatre brought added risk of fire: the Globe burned down in 1613, when a cannon used for special effects in a production of Henry VIII misfired, setting the thatching over the stage ablaze. Although the theatre was destroyed, the only injury reported was one unfortunate man whose breeches were set on fire. (Quick-thinking theatergoers extinguished the flames by dousing him with ale.)

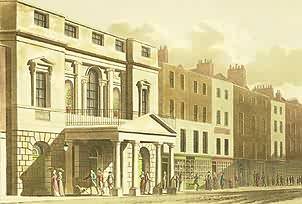

The real change came with the Restoration, when the re-opening of the theatres was celebrated with a host of innovations. The most prominent of these, of course, was the appearance of actresses in female roles that had previously been played by boys. Another, perhaps less-discussed innovation was the rash of theatre-building, including venues at Lincoln’s Inn Fields (1661) Drury Lane (1663), the Haymarket (1720), and Covent Garden (1731). Unlike their open-air predecessors, these new venues were fully enclosed. This meant performances were no longer limited to daylight hours, but it also meant that all performances, even those staged during the day, required artificial lighting. And artificial lighting meant open flames—either candles or oil lamps—and lots of them.

When we consider the combination of open flames and rowdy crowds—capacity in the new theatres rose from 650 seats at Drury Lane in 1700 to 3,600 by the time of the 1809 fire—the number of theatre fires is no longer surprising. In those days before electricity, the theatre at Drury Lane burned twice (in 1672 and again in 1809), as did the one at Covent Garden, aka the Royal Opera House (in 1808 and 1856). Ironically, only fifteen years earlier, in 1794, the Drury Lane theatre had installed a fire curtain made of iron—the first theatre in London to do so—along with large water tanks beneath the roof that could be used for special effects as well as fire safety.

With all these precautions in place, how, then, did it burn? No one knows. The theatre season was greatly subdued during Lent, with fewer plays being performed, and nothing, not even a rehearsal, was taking place on that Friday night in 1809. Since the theatre was apparently empty, there were no injuries, but from the incident we get the wonderful (if apocryphal) account of Richard Brimsley Sheridan—playwright, Member of Parliament, and manager of the Drury Lane theatre, who in 1794 had bankrolled the construction of the enormous new theatre from his own private fortune—watching the blaze from a nearby pub. When urged by his friends to go home, he is reported to have said, “Can a man not enjoy a glass of wine by his own fireside?”

Of course, from a writer’s perspective, the destruction of an empty building makes for dull fiction. So for the purposes of my story, I filled the theatre to its full 3,600-seat capacity and staged a production of Handel’s oratorio Esther. Besides being suitably sober for Lent, it contains a passionate duet between Esther and the king that made it a natural choice for Too Hot to Handel, certainly the most romantic of the John Pickett mysteries. And the fact that so little is known about the cause of the fire gave me the freedom to create my own “what if?” scenario.

Click here to see Sheri’s photos of the Drury Lane theatre before and after the fire in 1809.

About Too Hot to Handel

When a rash of jewel thefts strikes London, magistrate Patrick Colquhoun resolves to deploy his Bow Street Runners to put astop to the thefts. The Russian Princess Olga Fyodorovna is to attend a production of Handel’s Esther at Drury Lane Theatre,where she will wear a magnificent diamond necklace. The entire Bow Street force will be stationed at various locations around the theatre—including John Pickett, who will occupy a box directly across the theatre from the princess.

In order to preserve his incognito, Pickett must appear to be nothing more than a private gentleman attending the theatre. Mr. Colquhoun recommends that he have a female companion—a lady, in fact, who might prevent him from making any glaring faux pas. But the only lady of Pickett’s acquaintance is Julia, Lady Fieldhurst, to whom he accidentally contracted a Scottish irregular marriage several months earlier, and with whom he is seeking an annulment against his own inclinations—and for whom he recklessly declared his love, secure in the knowledge that he would never see her again.

The inevitable awkwardness of their reunion is forgotten when the theatre catches fire. Pickett and Julia, trapped in a third tier box, must escape via a harrowing descent down a rope fashioned from the curtains adorning their box. Once outside, Pickett is struck in the head and left unconscious. Suddenly it is up to Julia not only to nurse him back to health, but to discover his attacker and bring the culprit to justice.

Note: This book will be released on June 22, 2016. However, the previous book in the series is available.

Excerpt

Pickett opened the door of the theatre box, and immediately stepped back as he was struck with a wall of heat. The corridor was alive with flame, and as they stood staring into the inferno, a burning beam from the ceiling fell almost at their feet. He slammed the door shut.

“We won’t be going out that way,” he remarked, glancing wildly about the box for some other method of exit. He seized one of the heavy curtains flanking the box and pulled until it collapsed into his arms in a pile of red velvet. He located the edge and began ripping it into long strips.

“What are you doing?” asked her ladyship, her voice muffled by the folds of his handkerchief over her mouth.

Pickett jerked his head toward the sconce mounted on the wall between their box and its neighbor. Its many candles, so impressive only moments ago, now appeared pale and puny compared to the flames dancing all around them.

“I’m making a rope to tie to that candelabrum. You can climb down into the pit and escape from there. And don’t wait for me. As soon as your feet reach the floor, I want you to forget everything you ever learned about being a lady—push, shove, do whatever you have to do, but GET OUT, do you understand?”

“And what about you, Mr. Pickett?”

He glanced at the brass fixture. “I’m not sure if it will bear my weight, my lady. I suppose I’ll have to try—I don’t much fancy my chances in the corridor—but I’ll not make the attempt until I see you safely down.”

She leaned over the balustrade and looked past the three tiers of boxes to the pit some forty feet below, then turned back to confront Pickett. “Setting aside the likelihood that I would lose my grip and plummet to my death, do you honestly think I would leave you alone up here, to make your escape—or not!—as best you might? No, Mr. Pickett, I will not have it! Either we go together, or we do not go at all!”

The crash of falling timbers punctuated this statement, and although there was nothing at all humorous in the situation, he gave her a quizzical little smile. “ ‘ ’Til death do us part,’ Mrs. Pickett?”

She lifted her chin. “Just so, Mr. Pickett.”

The author is offering a trade-size paperback ARC of Too Hot to Handel to a random commenter.

About the Author

At the age of sixteen, Sheri Cobb South discovered Georgette Heyer, and came to the startling realization that she had been born into the wrong century. Although she doubtless would have been a chambermaid had she actually lived in Regency England, that didn’t stop her from fantasizing about waltzing the night away in the arms of a handsome, wealthy, and titled gentleman.

At the age of sixteen, Sheri Cobb South discovered Georgette Heyer, and came to the startling realization that she had been born into the wrong century. Although she doubtless would have been a chambermaid had she actually lived in Regency England, that didn’t stop her from fantasizing about waltzing the night away in the arms of a handsome, wealthy, and titled gentleman.

Since Georgette Heyer was dead and could not write any more Regencies, Ms. South came to the conclusion she would simply have to do it herself. In addition to her popular series of Regency mysteries featuring idealistic young Bow Street Runner John Pickett (described by All About Romance as “a little young, but wholly delectable”), she is the award-winning author of several Regency romances, including the critically acclaimed The Weaver Takes a Wife.

A native and long-time resident of Alabama, Ms. South recently moved to Loveland, Colorado, where she has a stunning view of Long’s Peak from her office window.

![By Isaac Cruikshank (publisher- Willm. Holland, London) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://susanaellisauthor.blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/by-isaac-cruikshank-publisher-willm-holland-london-public-domain-via-wikimedia-commons.png?w=714)