Today on Susana’s Parlour, Jude Knight and I have something special: a stand-alone short story with two characters from the Bluestocking Belles’ holiday box set, Mistletoe, Marriage, and Mayhem. Mary, the heroine of Jude’s story, Gingerbread Bride, meets Agatha Tate, Lady Pendleton, the mother of Julia Tate, the heroine of my story, The Ultimate Escape. In this episode, Lady Pendleton is just returning from a two-week journey into the twentieth century. Yes, she is a time-traveling Regency lady (who has appeared on this blog on several occasions in the past).

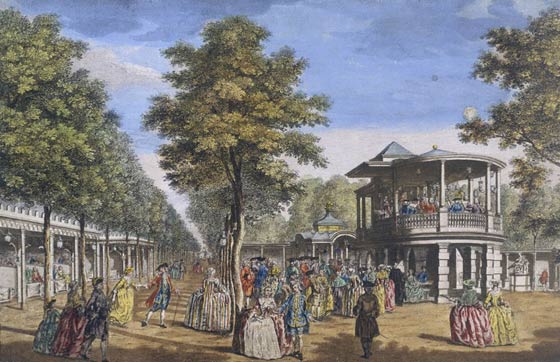

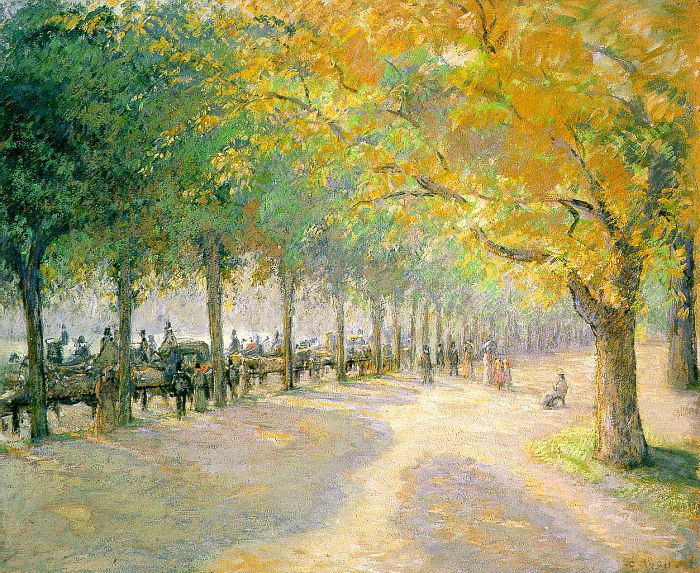

Agatha Tate staggered backwards as her feet touched the ground until, unable to reclaim her balance, she toppled over onto the soft grass at Hyde Park.

“Wh-at?” She put a hand to her aching temple and tried to regain her bearings. “Where am I?”

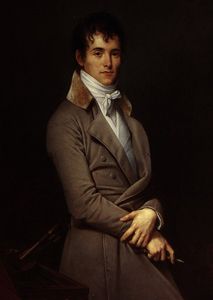

Agatha Tate, Lady Pendleton

She opened her eyes and could see a vague image of a young girl in front of her. A girl who had likely seen her materialize out of nowhere, she realized as her wits were restored to her. Good heavens! How was she going to explain something was… well… unexplainable?

The girl—a young woman really, Agatha could see as her vision cleared—stepped forward, blinking rapidly. “May I help you?”

“Uh… who are you?” Agatha asked, her head still throbbing. “How long have you been there?”

Agatha pulled herself up into a sitting position and cast about for her shopping bag, which had landed in a nearby bush. “Oh my, can you get that for me, my dear? I need to change my attire before anyone sees me.”

She was still wearing her animal print leather jeans and denim jacket, which was certain to startle an inhabitant of London in 1799. Of course, she should have changed to her original clothing prior to leaving the twentieth century, but she’d been so stricken by the need to see her family again that she’d collected her bag, pulled out the stone, and uttered the gypsy’s spell before the thought could occur to her.

“Well, before anyone ELSE sees me. I shouldn’t want to cause a scandal.”

Mary Pritchard

The bemused young lady fetched the bag and handed it to her. Agatha could see that her bright red hair was tousled and she seemed to be short of breath.

“Mary Pritchard, ma’am, at your service.” The young lady curtseyed politely.

“A pleasure to meet you, Miss Pritchard. Please allow me to introduce myself. I am not usually so rag-mannered, but since we have met in such unconventional circumstances…. Oh dear, there I go again! I am Lady Pendleton. My husband is Lord Pendleton, of Wittersham.”

“I am pleased to make your acquaintance, my lady.” She glanced at their surroundings, and returned her gaze toward Agatha with a reassuring smile. “We are hidden here, I think. I will keep a lookout un case Viscount B… in case anyone comes this way while you are changing.”

Agatha smiled, feeling a bit sheepish. “How very kind of you, Miss Pritchard. I was just about to ask if you would do me that small favor.”

She took the bag behind a bush and began to tug at the tight leather jeans. “Oh, I know I shouldn’t have had that last Big Mac,” she groaned.

Upon seeing the look of bewilderment on Miss Pritchard’s face, Agatha rolled her eyes. She already had a great deal to explain to the kind young woman. She’d better watch her tongue from her on in.

She coughed. “I’m afraid I’ve been over-indulging during the past fortnight. I hope my old clothes will still fit.”

“Have you traveled far?” Miss Pritchard asked politely.

Agatha grinned. “You could say that, I suppose.”

A crashing further back in the woods startled them, particularly Miss Pritchard, whose hand went to her chest as she turned toward the origin of the sound. She appeared frightened out of her skin.

Lady Pendleton pulled her yellow morning gown over her head. “Are you well, my child?”

I’m the one who has traveled 200 years and she’s the one who looks white enough to be a ghost.

“I… ah… you must wondering, ma’am, at my being here without an escort. That sound is, I think, my escort. If he finds me, would you be kind enough to say I am with you?”

The poor girl was trembling! Agatha stepped out from behind the bush and folded the girl into her embrace. Why she looked to be only a year or two older than her own daughter Julia!

“Your escort… attacked you? How did that happen?”

After a brief moment, Mary returned her embrace. She was a brave one—or perhaps foolish—to trust a complete stranger, particularly under these circumstances.

“I refused his proposal, and he thought to force me. I… ah… punched him in… ah… I distracted him and ran.”

What are Miss Pritchard’s parents thinking to allow her to be escorted by such a villain?

Miss Pritchard bit her lip. “I do not know what to do. If I tell my aunt, she will say that we must marry, and I would rather throw myself into the Thames than marry a man who only wants my money.” She sighed. “Actually, I would rather throw him into the Thames.”

Agatha straightened up. “This… this… Boswell won’t harm you as long as I’m here, my child.” She grinned. “The Serpentine is a great deal closer. Will that do instead, do you think?”

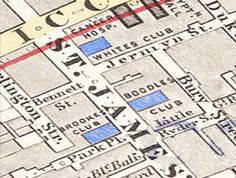

No. 42, Grosvenor Square, the Pendletons’ London home

She turned her back. “Hurry, do me up and we’ll away from here. I live in Grosvenor Square; it’s not too far.”

The girl chuckled and hastened to oblige. Agatha gathered her discarded clothing and stuffed them into the bag, realizing she would have to keep on her twentieth century boots since she had left the old ones behind.

“Ma’am, I could not help but notice the manner of your arrival and your attire. Would you think me impertinent if I asked where you came from?”

Agatha swallowed. What to say? Perhaps she could avoid the question… a little while longer.

“It’s a long story. What concerns me most at the moment is what your parents could have been thinking to leave you alone with such a rogue.”

Miss Pritchard sighed. “I came to live with my aunt when my papa died. The rogue is her son, I am afraid. She is as keen to have the inheritance my papa left me as her son is.”

Agatha’s nostrils flared. “How disgraceful! Clearly, she is not a fit guardian. Is there no one else who can offer you protection, my dear?” She pressed her lips together. “My husband and I don’t hold with arranged marriages. Not for our three daughters, or for anyone else, if it can possibly be helped.”

She set a fast pace toward the Grosvenor Gate. She wasn’t about to allow this scoundrel to make off with Miss Pritchard under any circumstances, but it would be best if they avoid a direct confrontation.

“He doesn’t even want me,” her young charge burst out. “I heard him tell his friends that he would park me in the country while spent my lovely money!”

As they approached the gate, Agatha paused and looked cautiously behind her for any sign of a pursuer and sighed with relief at not seeing one. Followed by a moment of uncertainty. The more she thought about her own family and how they must have worried about her disappearance, the more eager she was to hurry home and beg their forgiveness. On the other hand, she wasn’t sure she was quite ready to confront them—particularly not her husband George. In any case, she couldn’t abandon this poor little dove to her mercenary aunt and odious cousin. What to do? What to do?

“I’ve got it,” she said. “Tea!”

“Tea would be very welcome,” said Mary. “I have no wish to go home until I decide what to do about beastly Bosville.”

Agatha knew of a delightful little bookshop on Mount Street that served tea, which frankly she had not enjoyed half so well during her travels into the future.

“Let us have a brief respite at my friend Mrs. Marlowe’s bookshop,” she suggested. “She is very cordial and serves the best tea and biscuits in Town.”

Mary’s face brightened. “I know it!” Mary said. “She has an excellent range of books.”

Suddenly she moved to one side, putting Agatha between her and the carriageway, where a dark-haired dandy was driving a phaeton at a furious pace out of the gate and into the street beyond.

“Forgive me,” she said, “I am not usually so nervous, but that was my cousin, and I would rather he did not see me at present. Although,” she added, “I suppose it is silly of me, for what could he do in all this crowd? And I will take care not to be alone with him again, you may be sure.”

Agatha shook her head. “He looked very angry. It’s best to avoid a confrontation. Let’s away to Mount Street and refresh ourselves while we plan our strategy.” She was thinking “strategies”, because she had to come up with one for her own situation as well.

The bookshop was as busy as ever, with several customers waiting their turn at the counter. Mary led them up the stairs to the tearoom, where little tables invited friendly conversation.

“Lady Pendleton, I hope you do not think me rude, but I could not help but notice your attire when you—er—arrived. And—it cannot be true, can it? You seemed to appear out of nowhere!”

Agatha blanched. A more prudent woman would not have considered confiding her situation—as strange as it was—to a young girl such as Mary, but then, Agatha had never been known for her prudence.

“I’ll have a cup of Bohea,” she told the waiter. “And some strawberry tarts if you have them. What would you like, my dear?”

“Souchong, please,” Mary said. “And strawberry tarts sound wonderful.”

After the waiter had departed, Agatha turned to Mary. She might as well get it over with. “When you saw me earlier today, I was wearing clothing from the twentieth century. I-uh- was visiting there for the past two weeks. I suppose you might call me—a sort of time traveler.”

Agatha’s hands were clammy. It sounded so ridiculous to say such a thing, and she wouldn’t have believed it herself if she hadn’t experienced it firsthand. But she was going to have to say it again—soon—to her husband, so she’d best get over her fears now rather than later

Mary opened her mouth and closed it again. “How marvelous,” she said at last. “I have traveled much of the world, but to travel in time? How wonderful!” She sat up straight in her chair, her eyes widened.

“Marvelous, yes, it is at that,” Agatha agreed. “Quite fascinating. An amusing and rather unconventional manner of escaping one’s problems. But now… I find myself having to face them after all.”

Mary nodded. “Running away does not solve things. Though it can win you time to find a solution.”

Their conversation was interrupted by the arrival of the tea. Agatha poured for both of them.

“You are wise for your age,” she commented as she passed her the plate of tarts.

Mary smiled. “Thank you, ma’am. I am on my own, you see, and must think for myself. And I am of age, though I know I look younger. My youth is a great disadvantage. Were I older, I could move to my own residence, and no one would be in the least scandalized.” She sighed.

Agatha leaned in and lightly stroked Mary’s arm. “I have three daughters at home. Julia, my eldest, is fourteen. I have missed them all so much, and my husband most of all. But I needed time to reflect on my situation, and knew my mother and aunts would only tell me to go back to my husband.”

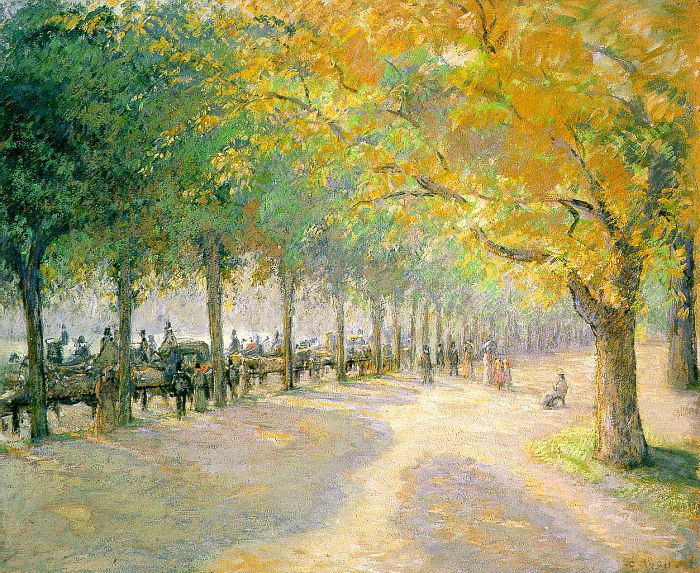

Lady Julia Tate (at age 27)

She shook her head. “Marriage is not something to be rushed into. My George and I married for affection and fell in love later. And for the most part, we have rubbed along very well. I never thought he would turn into a—despot.” She winced, knowing in her heart that George was not a despot. Someone had wounded his pride. That holier-than-thou William Wilberforce, who despised some of her political friends because he disapproved of their morals.

Mary grimaced. “But are you going home now?”

Agatha’s mouth went dry and she took another sip of her tea.

“I am,” she said. “I must. I cannot abandon my daughters. Or my husband.”

“Of course not,” Mary agreed.

“But George must know that I won’t have a despot for a husband. While women do not have the sort of freedoms in this century that they will have in the future,”—she saw Mary’s eyes widen in surprised—“we do have options, and he must surely know I would not hesitate to take some of them, undesirable though they would be.”

She licked her lips with cautious hope. “If I know my George, though, he has long ago forgotten his anger amidst his concern for my absence.” She smiled as she imagined a tender reconciliation between them. She felt a sense of calm.

Taking the last sip of tea, she set her cup down. “It appears that my path is quite clear. I must return home and have a serious discussion with my husband. As for you, my dear, I wonder if you haven’t any other relatives you could appeal to, since clearly these Bosvilles are not suitable.”

Mary’s face brightened. “I wonder that I did not think of that! Yes, indeed! I have three more aunts, though I have not met them. Papa said I was to come to London. He thought Aunt Bosville might help me to find a husband.” Her color deepened, her fair skin showing her embarrassment. “I find I am not in the fashionable mode, however. Being raised on a naval ship does not prepare one to talk nonsense, and faint, and be ridiculously frilly and the like. And then…” she gestured at her bright red hair and freckles, “there is how I look.”

Agatha raised an eyebrow. “I see nothing amiss with your appearance. Your coloring may not be the fashion this year, but it does not prevent you from having an appeal of your own. Indeed, my eldest daughter is flame-haired and freckled, and I am quite certain she will grow into her own beauty when she past the tomboy phase.” She grinned. “Red hair is quite popular in the twentieth century. I observed that many of the younger ladies had deliberately colored their hair red, or at least a portion of it.” She frowned. “Of course, there were also shades of blue and green that I could not like at all, but that was the way of things—or will be, I should say. Society is so much more liberated in the future.”

Mary leaned forward. “Lady Pendleton, do you think… Could you tell me how you came to travel through time? Could I do it?”

Agatha wrinkled her brow. “Oh no, my dear! I think it would be quite ill-advised for someone so young to venture off into a completely different world. You may be certain I will not breathe a word of it to any of my daughters, at least not until they are old enough to have learned to resolve their problems rather than try to avoid them. No indeed, dear Mary, we must find a rather more conventional solution to your dilemma.”

“I am familiar with adventures, Lady Pendleton. I have been in a number of tight spots in many parts of the world. Though I have needed rescue from time to time, and I suppose I cannot expect Rick—Lieutenant Redepenning—to follow me two hundred years into the future.”

Now this was a promising development. “This Rick-er-Lieutenant Redepenning… you say he has come to your rescue in the past? Sounds like a delightful young man. The two of you appear to have a great deal in common. Is he eligible, do you think?” She winked. “I must confess that I would like to see my daughter Julia make a match with Oliver, who lives next door to us in Wittersham. They have been close friends forever.” She sighed. “Although it remains to be seen how well they deal with each other as adults.”

“Things can certainly change when one grows up, Mary sighed. “We were good friends when we were younger, but now… Lady Pendleton, a friend would visit a friend, would he not? If he were in London, and she were in London? A lady cannot call upon a gentleman, after all. Aunt would not even allow me to send a note! At first he was recovering from his injury, but he has been seen about Town these past six weeks and has not been to see me.” She sighed again, more deeply this time. “No, eligible or not, Rick the Rogue is not interested in plain Mary Pritchard.”

Then she brightened. “I will go to my aunts in Haslemere, Lady Pendleton. I will make the arrangements today.”

“Do you need a place to stay before you leave, Miss Pritchard?” Agatha patted her hand. “You would be welcome, if you think your return to Lady Bosville’s house would put you at risk.”

Mary shook her head. “I am quite sure that is not necessary, my lady. My cousin is unlikely to dare anything further. If he should return home, that is. He often stays away for days at a time.”

“I do hope that is the case, dear. However,” she added in a maternal tone, “Do not neglect to hire a post chaise, and your own outriders. You have a maid who can accompany you, I take it?”

“The public coach goes straight through to Haslemere, where my aunts live. Yes, I do believe it is the perfect solution. Thank you for your counsel, Lady Pendleton. And best of luck with your own reunion. I am certain your family will be over-the-top excited to have you back again!”

I hope so too, Agatha thought. In any case, it was time she found out. She rose from her seat and reached for Mary’s hand.

“It was a great pleasure to meet you, Miss Pritchard. My sincere thanks for your assistance in the park earlier. I can trust on your discretion, I suppose?”

At Mary’s nod, she clasped Mary’s shoulder. “I wish you well on your journey. And if you need any further assistance, please send for me at Grosvenor Square. Number forty-two.”

And the two of them departed the bookshop to face their own separate destinies.

Click here to read the story from Mary Pritchard’s point of view.

Click here for more information about Mistletoe, Marriage, and Mayhem.

Join us on Facebook for our launch of Mistletoe, Marriage and Mayhem on November 1, 2015.

Our Christmas Party Box Rafflecopter is here.

Celebrate with us!