Romance of London: Strange Stories, Scenes And Remarkable Person of the Great Town in 3 Volumes

John Timbs

John Timbs (1801-1875), who also wrote as Horace Welby, was an English author and aficionado of antiquities. Born in Clerkenwell, London, he was apprenticed at 16 to a druggist and printer, where he soon showed great literary promise. At 19, he began to write for Monthly Magazine, and a year later he was made secretary to the magazine’s proprietor and there began his career as a writer, editor, and antiquarian.

This particular book is available at googlebooks for free in ebook form. Or you can pay for a print version.

The word “Bubble” as applied to any ruinous speculation, was first applied to the transactions of the South Sea Company, in the disastrous year 1720. It originated in the exaggerated representations of the sudden riches to be realized by the opening of new branches of trade to the South Sea, the monopoly of which was to be secured to the South Sea Company, upon their pretext of paying off the National Debt. The Company was to become the richest the world ever saw, and each hundred pounds of their stock would produce hundreds per annum to the holder. By this means the stock was raised to near 400; it then fluctuated, and settled at 330.

Exchange Alley was the seat of the gambling fever;* it was blocked up every day by crowds, as were Cornhill and Lombard Street with carriages. In the words of the ballads of the day:—

There is a gulf where thousands fell,

There all the bold adventurers came;

A narrow sound, though deep as hell,

‘Change Alley is the dreadful name.—Swift

Then stars and garters did appear

Among the meaner rabble;

To buy and sell, to see and hear

The Jews and Gentiles squabble.

The greatest ladies thither came,

And plied in chariots daily,

Or pawned their jewels for a sum

To venture in the Alley.

Innumerable bubble companies soon started up, by which one million and a half sterling was won and lost in a very short time. The absurdity of the schemes was monstrous: one was “a company for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know where it is.” In all these bubbles, persons of both sexes alike engaged; the men meeting their brokers at taverns and coffee-houses, and the ladies at the shops of milliners and haberdashers; and in Exchange Alley, shares in the same bubble were sold, at the same instant, then per cent. Higher at one end of the Alley than the other. Meanwhile, the Minister warmed the nation, and the King declared such projects unlawful, and trafficking brokers were liable to 5,000l penalty. The companies were dissolved, but others as soon sprung up. The folly was satirized in caricatures and “stock-jobbing cards.” When Sir Isaac Newton was asked about the continuance of the rising of the South Sea stock, he answered that he could not calculate the madness of the people…

Among the victims was Gay, the poet [author of The Beggar’s Opera], who having had some South Sea Stock presented to him, supposed himself to be the master of 20,000l: his friends importuned him to sell, but he refused, and profit and principal were lost. The ministers grew more alarmed, the directors were insulted in the streets, and riots were apprehended; a run commenced upon the most eminent goldsmiths and bankers, some of whom absconded.

The Committee of Secrecy reported to Parliament the results of their enquiry, showing how false and fictitious entries had been made in the books, erasures and alterations made, and leaves torn out; and some of the most important books had been destroyed altogether. The properties of many thousands of persons, amounting to many millions of money, had been away with. Fictitious stock had been distributed among members of the Government, by way of bribe, to facilitate the passing of the Bill. One of the Secretaries to the Treasury had received 250,000l, as the difference in the price of some stock, and the account of the Chancellor of the Exchequer showed 794,451l. He proved the greatest criminal, and was expelled the House, all his estate seized, and he was committed a close prisoner to the Tower of London. Next day Sir George Casual, of a firm of jobbers who had implicated in the business, was expelled the House, committed to the Tower, and ordered to refund 250,000l. Mr. Craggs the elder died the day before his examination was to have come on. He left a fortune of a million and a half, which was confiscated for the benefit of the sufferers. Every director was mulcted [fined], and two millions and fourteen thousand pounds were confiscated, each director being allowed a small residue to begin the world anew.

The history of the Bubble and other speculations contemporaneously with the South Sea scheme is well narrated in Charles Mackay’s Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions, vol. i. Pp. 45-84.

It was about the year 1688 that the world ‘stock-jobber’ was first heard in London. In the short space of four years a crowd of companies, every one of which confidently held out to subscribers the hope of immense gains, sprang into existence: the Insurance Company, the Paper Company, the Lutestring Company, the Pearl Fishery Company, the Glass Bottle Company, the Alum Company, the Blythe Coal Company, the Sword-blade Company. There was a Tapestry Company, which would soon furnish pretty hangings for all the parlours of the middle class, and for all the bed-chambers of the higher.

Others included in Mackay’s publication were:

- The Copper Company

- The Diving Company (to investigate shipwrecks), which put on an impressive show of their advanced diving equipment on the Thames for fine gentlemen and ladies eager to be a part of such thrilling treasure-hunting

- The Greenland Fishing Company

- The Tanning Company

- The Royal Academy Company, which would educate 2000 winners of a lottery in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, French, Spanish, conic sections, trigonometry, heraldry, japanning, fortification, bookkeeping, and the art of playing the theorbo.

Some of these companies took large mansions and printed their advertisements in gilded letters. Others, less ostentatious, were content with ink, and met at coffee-houses in the neighbourhood of the Royal Exchange. Jonathan’s and Garraway’s were in a constant ferment with brokers, buyers, sellers, meetings of directors, meetings of proprietors. Time-bargains soon came into fashion. Extensive combinations were formed, and monstrous fables were circulated, for the purpose of raising or depressing the price of shares.

William Hogarth, Emblematical Print on the South Sea Scheme (1721). In the bottom left corner are Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish figures gambling, while in the middle there is a huge machine, like a merry-go-round, which people are boarding. At the top is a goat, written below which is “Who’l Ride”. The people are scattered around the picture with a sense of disorder, while the progress of the well-dressed people towards the ride in the middle represents the foolishness of the crowd in buying stock in the South Sea Company, which spent more time issuing stock than anything else.

Our country witnessed for the first time those phenomena for which a long experience has made us familiar—a mania, of which the symptoms were essentially the same with those of the mania of 1721, of the mania of 1825, of the mania of 1845, seized the public mind. An impatience to be rich, a contempt for those slow but sure gains which are the proper reward of industry, patience and thrift, spread through society. The spirit of the cogging dicers of Whitefriars took possession of the grave senators of the City, wardens of trades, deputies, aldermen. It was much easier and much more lucrative to put forth a lying prospectus, announcing a new stock, to persuade ignorant people that the dividends could not fall short of twenty per cent., and to part with 5,000l of this imaginary wealth for ten thousand sold guineas, than to load a ship with well-chosen cargo for Virginia or the Levant. Every day a new bubble was puffed into existence, rose buoyant, shone bright, burst, and was forgotten.

*Mr. E.M. Ward, R.A., has painted, with wonderful effect, “‘Change Alley during the South Sea Bubble,” a picture very properly placed in our National Gallery. [Currently Tate]

Susana’s remarks

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

- You aren’t going to win a big lottery prize. Or the Publishers’ Clearing House Sweepstakes. Or find buried treasure in your backyard.

- When someone—even if it’s the Pope himself—offers you something that’s too good to be true, it really is too good to be true. Don’t be fooled.

- Don’t be greedy. Be satisfied with “slow but sure gains” that are the reward of industry, patience and thrift.”

Romance of London Series

- Romance of London: The Lord Mayor’s Fool… and a Dessert

- Romance of London: Carlton House and the Regency

- Romance of London: The Championship at George IV’s Coronation

- Romance of London: Mrs. Cornelys at Carlisle House

- Romance of London: The Bottle Conjuror

- Romance of London: Bartholomew Fair

- Romance of London: The May Fair and the Strong Woman

- Romance of London: Nancy Dawson, the Hornpipe Dancer

- Romance of London: Milkmaids on May-Day

- Romance of London: Lord Stowell’s Love of Sight-seeing

- Romance of London: The Mermaid Hoax

- Romance of London: The Bluestocking and the Sweeps’ Holiday

- Romance of London: Comments on Hogarth’s “Industries and Idle Apprentices”

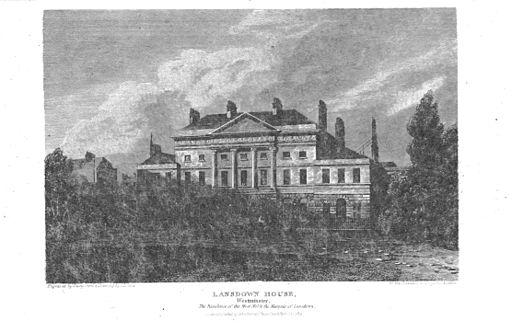

- Romance of London: The Lansdowne Family

- Romance of London: St. Margaret’s Painted Window at Westminster

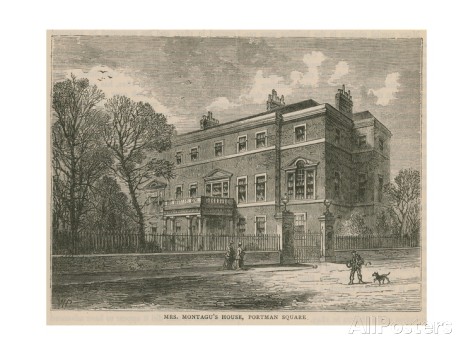

- Romance of London: Montague House and the British Museum

- Romance of London: The Bursting of the South Sea Bubble

- Romance of London: The Thames Tunnel

- Romance of London: Sir William Petty and the Lansdowne Family

- Romance of London: Marlborough House and Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough

- Romance of London: The Duke of Newcastle’s Eccentricities

- Romance of London: Voltaire in London

- Romance of London: The Crossing Sweeper

- Romance of London: Nathan Mayer Rothschild’s Fear of Assassination

- Romance of London: Samuel Rogers, the Banker Poet

- Romance of London: The Eccentricities of Lord Byron

- Romance of London: A London Recluse

![By Isaac Cruikshank (publisher- Willm. Holland, London) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://susanaellisauthor.blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/by-isaac-cruikshank-publisher-willm-holland-london-public-domain-via-wikimedia-commons.png?w=714)