published by Rudolph Ackermann in 3 volumes, 1808–1811.

The annexed print gives an accurate and interesting view of this abode of wretchedness, the Pass-Room. It was provided by a late act of Parliament, that paupers, claiming settlements in distant parts of the kingdom, should be confined for seven days previous to their being sent off to their respective parishes; and this is the room appointed by the magistracy of the city for one class of miserable females. The characters are finely varied, the general effect broad and simple, and the perspective natural and easy.

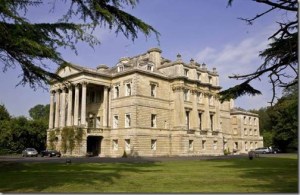

Bridewell, as early as King John, was a royal palace, formed partly out of the remains of an ancient castle, the western Arx Palatina of the city, and the residence of several of our monarchs; but in process of time became neglected: till, in 1522, Henry VIII. rebuilt it in a most magnificent manner, for the reception of the Emperor Charles V. who in that year paid him a visit: Charles was, however, lodged in Black Friars, and his suite in the new palace. A gallery of communication was thrown over Fleet-Ditch, and a passage cut through the city wall to the emperor’s apartments. Henry often lodged here, particularly in 1529, when the question of his marriage with Queen Catherine was agitated in Black Friars. It fell afterwards to decay, and was begged by the pious Prelate Ridley from Edward VI. to be converted to some charitable purpose: that of a house of correction for vagabonds of each sex and all denominations was determined on. It also answers another purpose; it is a foundation for youth who are bound apprentices to different trades under what are called Arts-Masters*; and forms part of the great plan of benevolence adopted by the amiable Edward VI. when he endowed the city hospitals, of which this is one. It is situated in Bridge-street, Black Friars, and gives the name to Bridewell precinct in the neighbourhood; the whole building forms a square, consisting of the houses of the arts-masters, who are six in number, the prisons for the men and women, the committee-room, and a chapel.

The men’s prison is a good brick building, on the western side, consisting of thirty-six sleeping-rooms, and seven other apartments. Every man has a room to himself, containing a bedstead, straw in a sacking, a blanket, and coverlet. The other rooms consist of workshops, a sick-room, which is a very comfortable apartment, and a larger, in which idle apprentices are confined separate from the other prisoners. In the working-room are junk and oakum, which the prisoners pick, and mills where they grind corn. The task-master’s apartments, and the women’s prison, which is separate from the men’s, are on this western side. The committee-room is on the south side, where a committee of the governors meet every week to examine the prisoners. There are excellent regulations to this prison: in the cellar is a bath, in which the prisoners are occasionally washed; but there is no yard for them to walk in, which is a great defect in any house of this description.

The original plan of this hospital, combined and incorporated with the hospitals of Christ and St. Thomas, was so benevolent, and of such comprehensive utility, that it is worthy to be followed, improved, and completely executed, by the wisest and best of men, in the wisest and best of times. It was to “train up the beggar’s child to virtuous industry, so that from him no more beggars should spring; to succour the aged and the diseased; to relieve the decayed housekeeper and the indigent; and to compel the wretched street-walker and the vagabond to honest labour.” Its design was, to include every class of the unfortunate, the helpless, and the depraved. To effect this, the governors were instituted, and are, as a body corporate, empowered to make* “all manner of wholesome and honest ordinances, statutes, and rules, for the good government of the poor in Bridewell.” Many very important alterations have taken place in this hospital within the last century, particularly in the years 1792 and 1793. Pennant, whose account of London was published in 1793, states the number of arts-masters at twenty; they are now reduced to six. The number of apprentices taught and maintained, he does not state; in the year 1717, they amounted to one hundred and three received within the year, and in 1718, to ninety-four. — Vide Speed. The apprentices are now reduced to thirty.

The late improvements in the buildings at Bridewell have been very great. The entrance is by a very noble front, of the Doric order; on the key-stone of the arch is a head of the illustrious founder. The apartments in this center are destined for the residence of the chamberlain of the city of London, who is also treasurer. Adjoining this building are six new houses, corresponding with the other houses in Bridge-street, the back parts of which occupy what was before a court-yard, in which resided several of the arts-masters. A new chapel, and a very noble apartment called the committee-room, complete the improvements on the eastern and principal side. On the north have been some alterations. The male prisoners are removed to a new building erected on the western side; and the arts-masters, who lived on that site, are removed to houses erected for them on the north side.

The court-room is an interesting piece of antiquity, as on its site were held courts of justice, and probably parliaments, under our early kings. At the upper end are the old arms of England; and it is wainscotted to a certain height with English oak, ornamented with carved work. This oak was formerly of that solemn colour which it attains by age, and was relieved by the carving being gilt. It must have been no small effort of ingenuity to destroy at one stroke all this venerable time-honoured grandeur: it was, however, happily achieved by daubing over with paint the fine veins and polish of the old oak, to make a very bad imitation of the pale modern wainscot; and other decorations are added in a similar taste.

On the upper part of the wall are the names, in gold letters, of benefactors to the hospital: the dates commence with 1565 and end with 1713. This is said to have been the court in which the sentence of divorce was pronounced against Catherine of Arragon, which had been concluded on in the opposite monastery of the Black Friars.

From this room is the entrance into the hall, which is a very noble one: at the upper end is a picture, by Holbein, representing Edward VI. delivering the charter of the hospital to Sir George Barnes, then lord mayor; near him are William, Earl of Pembroke, and Thomas Goodrich, Bishop of Ely. There are ten figures in the picture, besides the king, whose portrait is painted with great truth and feeling: it displays all that languor and debility which mark an approaching dissolution, and which unhappily followed so soon after, together – with that of the painter, that it has been sometimes doubted whether the picture was really painted by Holbein: his portrait, however, is introduced; it is the furthest figure in the corner on the right hand, looking over the shoulders of the persons before him.

On one side of this picture is a portrait of Charles II. sitting, and on the other that of James II. standing; they are both painted by Sir Peter Lely. Round the room are several portraits of the presidents and different benefactors, ending with that of Sir Richard Carr Glyn. The walls of this room are covered with the names of those who have been friends to the institution, written in letters of gold.

The new committee-room is finely proportioned, and in a very good style of architecture; as is the new chapel, which is divided from it by the portico, and which together occupy the whole back front of the eastern range of buildings.

The following is a list of the present officers of this hospital and Bethlem, founded by Edward VI. 1553:

- President of both Hospitals, Sir Richard Carr Glyn, Bart. Alderman.

- Treasurer to ditto, Richard Clark, Esq. Chamberlain of the city of London.

- Chaplain at Bridewell, Rev. Henry Budd, B. A.

- Physician to both, Thomas Munro, M. D.

- Surgeon to ditto, Bryan Crowther, Esq.

- Apothecary to ditto, Mr. John Haslam.

- Clerk to ditto, Mr. John Poynder.

- Steward to Bridewell, accomptant and receiver to both, Air. Bolton Hudson.

- Porter to Bridewell, Richard Weaver.

- Matron to ditto, Mary Rundle.

* These arts-masters were originally decayed tradesmen, and consisted of shoemakers, taylors, flax-dressers, orris and silk-weavers, &c. The apprentices used to be distinguished by a blue jacket and trowsers, and a white hat: their dress is now in the form of other people’s, distinguished only by a button bearing the head of the founder.