Amusements of Old London

William B. Boulton, 1901

“… an attempt to survey the amusements of Londoners during a period which began… with the Restoration of King Charles the Second and ended with the accession of Her Majesty Queen Victoria.”

In a country such as England that drew much more of its income from agriculture than manufacturing in this time period, it is interesting to note that the most popular time for holidays and festivities was late summer and autumn, when farming activities intensified. Just at the time when gentlemen itched to be in the country at their hunting and field sports, the peers were called to London for the rise of Parliament.

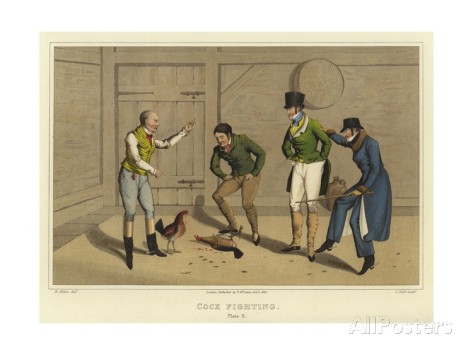

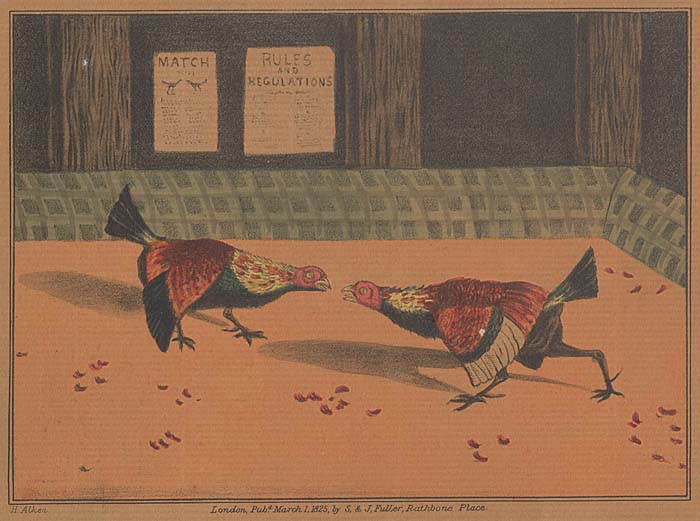

And yet it was in those months that this instinct of the English taught them to lay aside their cares and get what enjoyment they could from the means nearest at hand. Before the era of railways and cheap travelling the great mass of the population of London never went twenty miles from St. Paul’s, and the sport they enjoyed took the form of the delights provided by Hockley in the Hole, the Ducking Ponds, and the Cockpits… And yet, as the summer passed away, and the dog-days raised a heat from the cobblestones which drove the dogs themselves into the shade of alley and entry, the common people of London, instead of panting for the water-brooks or the sea-shore, prepared themselves for the great carnivals which were prepared for their delight in one or other of the great fairs of the town.

These annual gatherings followed each other in quick succession in the hot months of the year in the not very promising surroundings of Smithfield, or Southwark, or Westminster. The glory of these entertainments was at its zenith at the beginning of the eighteenth century…

…[T]heir origin was religious, their development commercial, and their apotheosis an unrestrained indulgence in pleasure or license…

The St. Bartholomew Fair

(see more on the origins of the fair on another blog post)

In the late seventeenth century, amidst all the rope dancers, jugglers, and puppet shows, a well-known actor by the name of Penkethman set up a theatrical booth. A plethora of theatrical entertainers followed, including Doggett (a comedian famous from the annual waterman’s race on the Thames), Miller (from Drury Lane), Bullock, Simpson, Colley Cibber (poet laureate and member of White’s), Quin, Macklin, Woodward, Shuter, and many more. “The theatrical movement, in fact, became so pronounced that as time went on most of the favourite actors of the day did not disdain to tread the boards in the temporary booths of the fair.”

The dramatic entertainments which were in fashion at the fairs… consisted almost invariably of some prodigious long-winded scheme dealing with such portentous subjects as “The Loves of the Heathen Gods,” “The Creation of the World,” “The Siege of Troy,” “Jephthah’s Rash Vow,” “Tamerlane the Great,” lightened up with much comic relief, in which an eccentric English character took a part totally irrelevant to the particular epic comprised in the plot. These productions came to be called “drolls,” and you may trace int hese drolls the germs of many forms of variety entertainment popular to-day, including, perhaps, that of English pantomime… The puppet-shows… followed the dramatic taste set by the actors.

Bartholomew Fair indeed became so great a nursery of dramatic talent that many actors afterwards famous obtained their first chance at Smithfield. The fair became a sort of theatrical exchange, where managers during their annual visits were often able to find the valuable recruits, and where strolling players from the provinces were accustomed to attend in the hope of engagements with regular companies.

…[T]he managers of the great theaters found it profitable to close their houses altogether… and take their companies to Smithfield, where they found they could earn more money from the audiences who flocked to their shows during the whole day than from the single performances of the patent theatres… Mr. Henry Fielding, for instance, fresh from Eton and Leyden, but without a guinea in his pocket… set up a booth, and for ten years provided an entertainment for the people at the fair… Fielding produced “The Beggars’ Opera” at Smithfield, occasionally trod the boards himself, and received the honour of a visit from the Prince and Princess of Wales in 1732, who were much delighted with his historical drama of “The Fall of Essex.”

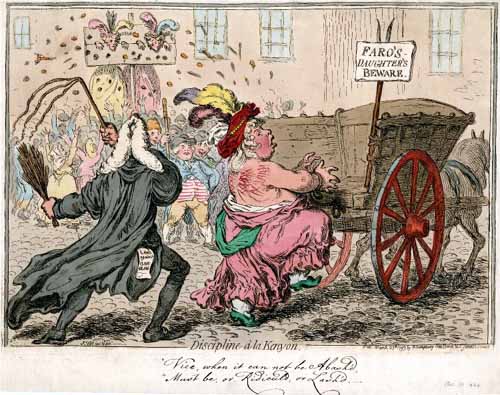

Unfortunately, the activities of the fair were periodically harassed by “persecution from the puritanical busybodies… [who] frequently succeeded in closing the booths, and left the fair to the gin-stalls, gaming-tables, and jugglers, diversions which were presumably less vicious in their eyes…” Sometimes the “puritanical spirits” would persuade the city government to disallow the booths on the night before the fair. “The ordinary attractions of the fair would then be enlivened by a riot of first-class dimensions, which always resulted in assault and battery, and sometimes in sudden death.”

The end of the theatrical entertainments at Smithfield came about when the powers-that-be limited the fair from fourteen days to three. Three days didn’t pay an actor or manager enough to make it worthwhile. At that point, the attractions changed to such things as menageries of wild beasts, or spectacles such as the “double-cow” or the “mermaid.” As the nineteenth century approached and the audiences became less naïve, the entertainments became slightly more sophisticated, with lion tamers putting their heads in the lion’s mouth, rope-dancing, magicians, peep-shows, etc. Just the chance of rubbing shoulders with nobles and even royalty was enough to draw people to St. Bartholomew’s.

It was no uncommon sight at St. Bartholomew’s, to see an exquisite like Chesterfield, or a great minister like Sir Robert Walpole, with his star on his breast, tasting the diversions of the fair alone and on foot. Parties of bloods from White’s and Almack’s were not above exchanging humorous badinage with the fruit-sellers, or the prettier of the strollers or acrobats, or even chucking them under the chin.

Southwark Fair

The Southwark Fair, on St. Margaret’s Hill near Southwark Town Hall, originated in the year 1550 and continued for more than two hundred years.

As the 7th of September came around in each year, the same gin stalls, gaming-tables, gingerbread stalls, and theatrical booths which had delighted Smithfield were packed up, taken across the river, and displayed in all their attractiveness to new audiences of South Londoners at Southwark.

Although smaller in scale than the fair in Smithfield, the acrobat and rope-dancing acts excelled at Southwark, primarily because of the more laissez-faire attitude of the local government. Mr. Cadman, who used to swing his way on a rope across the street from St. George’s Church tower to the mint, eventually “came to a sad end in attempting a bold flight across the Severn at Shrewsbury.”

The humours of Southwark Fair inspired Mr. Hogarth in one of his finest efforts, wherein are reflected so admirably the life of his times, and that excellent plate of Southwark Fair is as good an illustration as need be of the importance of the festival among the popular diversions of the middle of the eighteenth century. The greatly daring acrobat on the rope stretching from the church tower to the Mint, which is out of the picture, is the great Mr. Cadman himself; the artist on the slack rope on the other side of the picture is a back view of the Violante. Mr. Figg, the famous “Master of the Noble Science of Self-defence,” displays his honourable wounds on the right. His booth is round the corner and he is riding through the fair with very martial aspect to gather clients to witness a set-to between himself and some other bald-pated hero of the sword or quarter-staff. On the right of the pretty girl with the drum and the black page, who is effectively advertising the show which she represents, is Tamerlane the Great in full armour, being arrested by a bailiff. The enormous posters of the background, which almost blot out the church, and display the attractions of the Fall of Troy, the Royal Waxworks, and the wonderful performance of Mr. Banks and his horse, are all quite typical of the London fair, and Mr. Hogarth’s grim humour appears to perfection in the title of the show which he represents as tumbling into the street on the right, with its actors and orchestra and monkey on the pole, the “Fall Bagdad.” Note too the peep-show and the hag presiding over the gaming-table, and the pleasant glimpse of open country between the houses.

May Fair

See more about the May Fair here:

The End of the Great Fairs

These fairs mostly came to an end around the mid-eighteenth century, when the crowd became wilder, the entertainments more tawdry, and the patrons (such as the “great people of St. James’s”) harder to find. The days of when people could be entertained by simple things like tea gardens and fairs disappeared into the annals of history.