The following post is the twenty-sixth of a series based on information obtained from a fascinating book Susana obtained for research purposes. Coaching Days & Coaching Ways by W. Outram Tristram, first published in 1888, is replete with commentary about travel and roads and social history told in an entertaining manner, along with a great many fabulous illustrations. A great find for anyone seriously interested in English history!

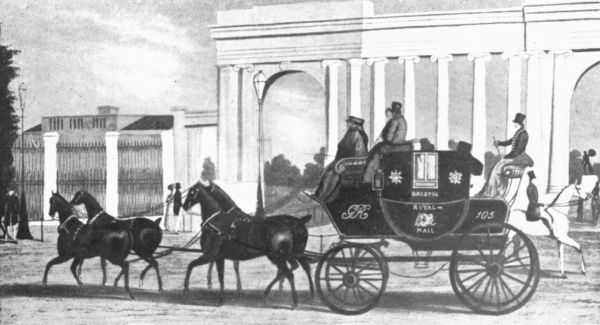

Portrait of a Flying Machine

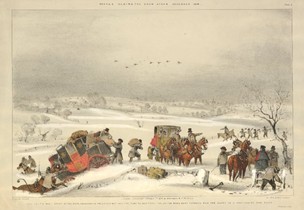

…they were principally composed of a dull black leather, thickly studded by way of ornament with broad black-headed nails, tracing out the panels in the upper tier of which were four oval windows, with heavy red wooden frames, or leather curtains. Upon the doors were displayed in large characters the names of the places whence the coach started, and where it was going to—another matter. The shape of the Flying Machine was a matter left much open to choice. You could ride in one shaped like a diving bell; or in one the exact representation of a distiller’s vat, hung equally balanced between immense back and front springs; or in one made after the pattern of a violoncello case—past all comparison the most fashionable shape. If my readers are tempted to cry why this thusness, I can only say because these violoncello-like Flying Machines hung in a more graceful posture—namely, inclining on to the back springs—and gave those who sat within it “the appearance of a stiff Guy Fawkes uneasily seated.” But this is a satiric touch, surely. To get on to the roofs, however. These generally rose into a swelling curve, which was sometimes surrounded by a high iron guard, after the manner of our more modern four-wheeled cabs. The coachman and the guard (who always held his carbine ready cocked upon his knee—an attitude which must have made inside passengers wish they had insured their lives) then sat together over a very long and narrow boot which passed under a large spreading hammercloth hanging down on all sides, and furnished with a most luxuriant fringe. Behind the coach was the immense basket, stretching far and wide beyond the body in which it was attached by long iron bars or supports passing beneath it. I am not surprised to learn that these baskets were never very great favourites, though their difference of price caused them to be frequently filled—but another proof of needs must when the devil drives—. And as for the notion of these Flying coaches when well on the road, it was “as a ship rocking or beating against a heavy sea’ straining all her timbers, with a low moaning sound as she drives over the contending waves.” With which extraordinary simile we may leave Flying Machines behind us—and any description of their successors too. For are not the models of the crack coaches in coaching’s primest age to be seen every day in Piccadilly? They are—and some very delightful rides can be had in them too.

The experience of “travelling in one of these perfected turn-outs”

Not that travelling in these perfected turn-outs was always like riding on a bed of roses, as I have had occasion frequently to point out, which consideration brings me to the inevitable comparison of the advantages of rail versus road. On which great subject much can be said on both sides, as a celebrated Attorney-General for Honolulu once remarked. De Quincey, for instance, may talk of the “fine fluent motion of the Bristol Mail,” and call up recollections in our minds of the modern Bristol Mail’s motion as anything but fluent; he may glorify “the absolute perfection of all the appointments about the carriage and the harness, their strength, their brilliant cleanliness, their beautiful simplicity, the royal magnificence of the horses; “but here is another side to the picture. I quote from Hone’s Table-books, an extract in the style of Jingle, and worthy of him.

“STAGE COACH ADVENTURES.

“INSIDE.—Crammed full of passengers—three fat fusty old men—a young Mother and sick child—a cross old maid—a poll parrot—a bag of red herrings—double-barrelled gun (which you are afraid is loaded)—and a snarling lap dog in addition to yourself. Awake out of a sound nap with the cramp in one leg and the other in a lady’s bandbox—pay the damage (four or five shillings) for gallantry’s sake—getting out in the dark at the half-way house, in the hurry stepping into the return coach and finding yourself next morning at the very spot you had started from the evening before—not a breath of air—asthmatic old woman and child with the measles—window closed in consequence—unpleasant smell—shoes filled with warm water—look up and find it’s the child—obliged to bear it—no appeal—shut your eyes and scold the dog—pretend sleep and pinch the child—mistake—pinch the dog and get bit.—Execrate the child in return—black looks—no gentleman—pay the Coachman and drop a piece of gold in the straw—not to be found—fell through a crevice—Coachman says ‘He’ll find it.’—Can’t—get out yourself—gone—picked up by the Ostler—no time for blowing up—Coach off for next stage—lose your money—get in—lose your seat—stuck in the middle—get laughed at—lose your temper—turn sulky—and turned over in a horse-pond.

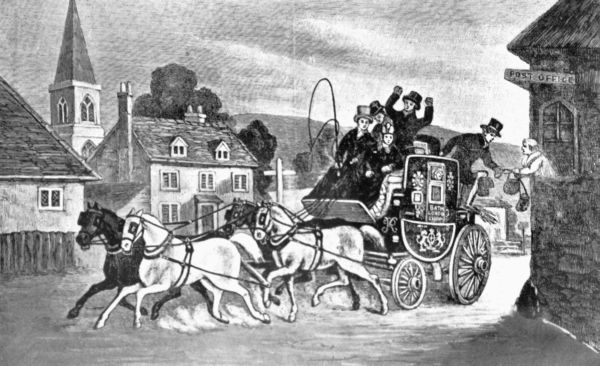

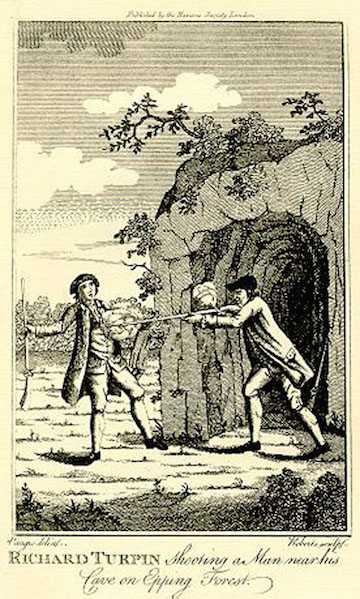

“OUTSIDE.—Your eye cut out by the lash of a clumsy Coachman’s whip—hat blown off into a pond by a sudden gust of wind—seated between two apprehended murderers and a noticed sheep-stealer in irons—who are being conveyed to gaol—a drunken fellow half asleep falls off the Coach—and in attempting to save himself drags you along with him into the mud—musical guard, and driver horn mad—turned over.—One leg under a bale of cotton—the other under the Coach—hands in breeches pockets—head in hamper of wine—lots of broken bottles versus broken heads.—Cut and run—send for surgeons—wounds dressed—lotion and lint four dollars—take post-chaise—get home—lay down—and laid up.”

Index to all the posts in this series

1: The Bath Road: The (True) Legend of the Berkshire Lady

2: The Bath Road: Littlecote and Wild William Darrell

3: The Bath Road: Lacock Abbey

4: The Bath Road: The Bear Inn at Devizes and the “Pictorial Chronicler of the Regency”

5: The Exeter Road: Flying Machines, Muddy Roads and Well-Mannered Highwaymen

6: The Exeter Road: A Foolish Coachman, a Dreadful Snowstorm and a Romance

7: The Exeter Road in 1823: A Myriad of Changes in Fifty Years

8: The Exeter Road: Basingstoke, Andover and Salisbury and the Events They Witnessed

9: The Exeter Road: The Weyhill Fair, Amesbury Abbey and the Extraordinary Duchess of Queensberry

10: The Exeter Road: Stonehenge, Dorchester and the Sad Story of the Monmouth Uprising

11: The Portsmouth Road: Royal Road or Road of Assassination?

12: The Brighton Road: “The Most Nearly Perfect, and Certainly the Most Fashionable of All”

13: The Dover Road: “Rich crowds of historical figures”

14: The Dover Road: Blackheath and Dartford

15: The Dover Road: Rochester and Charles Dickens

16: The Dover Road: William Clements, Gentleman Coachman

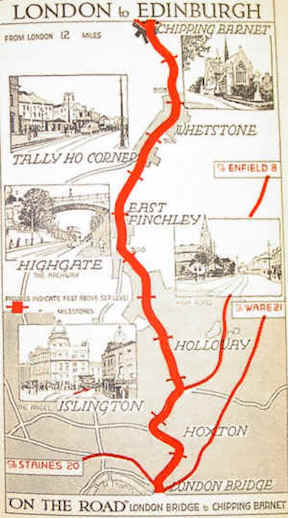

17: The York Road: Hadley Green, Barnet

18: The York Road: Enfield Chase and the Gunpowder Treason Plot

19: The York Road: The Stamford Regent Faces the Peril of a Flood

20: The York Road: The Inns at Stilton

21: The Holyhead Road: The Gunpowder Treason Plot

22: The Holyhead Road: Three Notable Coaching Accidents

23: The Holyhead Road: Old Lal the Legless Man and His Extraordinary Flying Machine

26: Flying Machines and Waggons and What It Was Like To Travel in Them