Romance of London: Strange Stories, Scenes And Remarkable Person of the Great Town in 3 Volumes

John Timbs

John Timbs (1801-1875), who also wrote as Horace Welby, was an English author and aficionado of antiquities. Born in Clerkenwell, London, he was apprenticed at 16 to a druggist and printer, where he soon showed great literary promise. At 19, he began to write for Monthly Magazine, and a year later he was made secretary to the magazine’s proprietor and there began his career as a writer, editor, and antiquarian.

This particular book is available at googlebooks for free in ebook form. Or you can pay for a print version.

Mayfair

From Wikipedia:

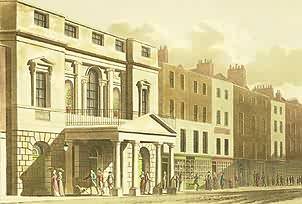

Mayfair was mainly open fields until development started in the Shepherd Market area around 1686 to accommodate the May Fair that had moved from Haymarket in St. James’s.

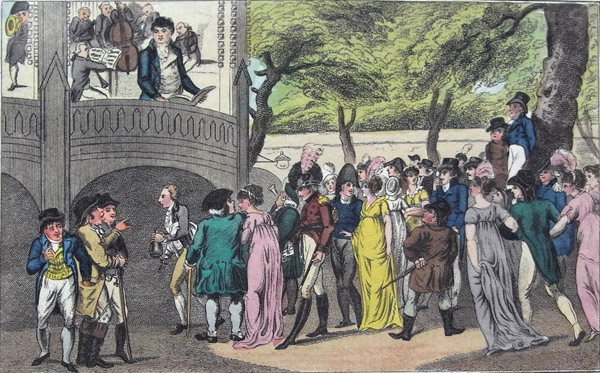

Mayfair was part of the parish of St Martin in the Fields. It is named after the annual fortnight-long May Fair that, from 1686 to 1764, took place on the site that is Shepherd Market. The fair was previously held in Haymarket; it moved in 1764 to Fair Field in Bow in the East End of London, after complaints from the residents.

Sir Thomas Grosvenor, 3rd Baronet married Mary Davis, heiress to part of the Manor of Ebury, in 1677; the Grosvenor family gained 40 hectares (100 acres) of Mayfair. Most of the Mayfair area was built during the mid 17th century to mid 18th century as a fashionable residential district, by a number of landlords, the most important of them being the Grosvenor family, which in 1874 became the Dukes of Westminster. In 1724 Mayfair became part of the new parish of St George Hanover Square, which stretched to Bond Street in the south part of Mayfair and almost to Regent Street north of Conduit Street. The northern boundary was Oxford Street and the southern boundary fell short of Piccadilly. The parish continued west of Mayfair into Hyde Park and then south to include Belgravia and other areas.

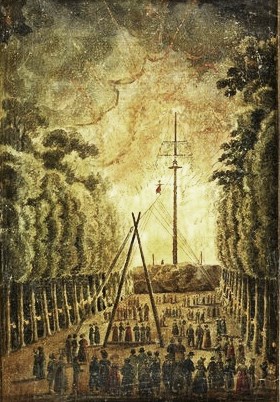

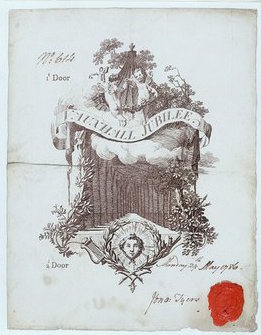

May Fair a Century Ago

We find a curious picture of this west-end carnival by that painstaking antiquary, John Carter, who, writing in 1816, says: “Fifty years have passed away since this place of amusement was at its height of attraction: the spot where the Fair was held still retains the name of May Fair… The market-house consisted of two stories: first story, a long and cross aisle for butchers’ shops, and, externally, other shops connected with culinary purposes; second story, used as a theatre at Fair-time for dramatic performances… Below, the butchers gave place to toy men and gingerbread-bakers. At present, the upper story is unfolded, the lower nearly deserted by the butchers, and their shops occupied by needy peddling dealers in small wares; in truth, a most deplorable contrast to what once was such a point of allurement. In the area encompassing the market building were booths for jugglers, prize-fighters both at cudgels and back-swords, boxing-matches, and wild-beasts. The sports not under cover were mountebanks, fire-eaters, ass-racing, sausage-tables, dice-ditto, up-and-downs, merry-go-rounds, bull-baiting, grinning for a hat, running for a shift, hasty-pudding-eaters, eel-divers, and an infinite variety of other similar pastimes.”

Tiddy Doll, Gingerbread Baker (NYPL Digital Library)

Tiddy Doll was a famed 18th century gingerbread vendor, a well-known sight amongst the butchers and toy-men, jugglers and fire-eaters at London’s Bartholomew Fair and Shepherd’s Market in Mayfair. He was even known to ply his wares at public executions, and can be seen in the lower right-hand corner of Hogarth’s Idle Prentice Executed at Tyburn, waving a spicy cake to the boisterous mob. His real name was apparently Ford, acquiring his nickname from a habit of ending his addresses to the crowd with the last lines of a popular ballad, “tid-dy did-dy dol-lol, ti-tid-dy ti-ti, tid-dy tid-dy, dol.” Wearing a white apron over his customary white gold laced suit, ruffled shirt, laced hat and feather and silk stockings, “like a person of rank,” his name was associated for many years with a person dressed out of character, as “you are as tawdry as Tiddy-doll; you are quite Tiddy-doll,” etc.

The Woman and the Anvil

One of the marvels of May Fair, in its latest revival, was the performance of a strong woman, the wife of a Frenchman, exhibited in a house in Sun Court, Shepherd’s Market. The following account is given by John Carter, and may be relied on, as Carter was born and passed his youthful days in Piccadilly [Carter’s Statuary]. He tells us that a blacksmith’s anvil being procured from White Horse Street, with three of the men, they brought it up, and placed it on the floor of the exhibition-room. The woman was short, but most beautifully and delicately formed, and of a most lovely countenance. She first let down her hair (a light auburn), of a length descending to her knees, which she twisted round the projecting part of the anvil, and then, with seeming ease, lifted the ponderous mass some inches from the floor. After this, a bed was placed in the middle of the room; when, reclining on her back, and uncovering her bosom, the husband ordered the smiths to place thereon the anvil, and forge upon it a horse-shoe! This they obeyed: by taking from the fire a red-hot piece of iron, and with their forging hammers completing the shoe with the same might and indifference as when in the shop at their constant labour. The prostrate fair one seemed to endure this with greatest composure, talking and singing during the whole process: then, with an effort, which to the bystanders appeared supernatural, she cast the anvil from off her body, jumping up at the same moment with extreme gaiety, and without the least discomposure of her dress or person. That there was no trick or collusion was obvious from the evidence: the spectators stood about the room with Carter’s family and friends; the smiths were strangers to the Frenchman, but known to Carter, the narrator. She next placed her naked feet on a red-hot salamander, without injury, the wonder of which was, however, understood even at that time.*

*Mr. Daniel, of Canonbury, thought the Strong Woman to have been Mrs. Allchorne, who died in Drury Lane in 1817, at a very advanced age. Madame performed at Bartholomew Fair in 1752.

Romance of London Series

- Romance of London: The Lord Mayor’s Fool… and a Dessert

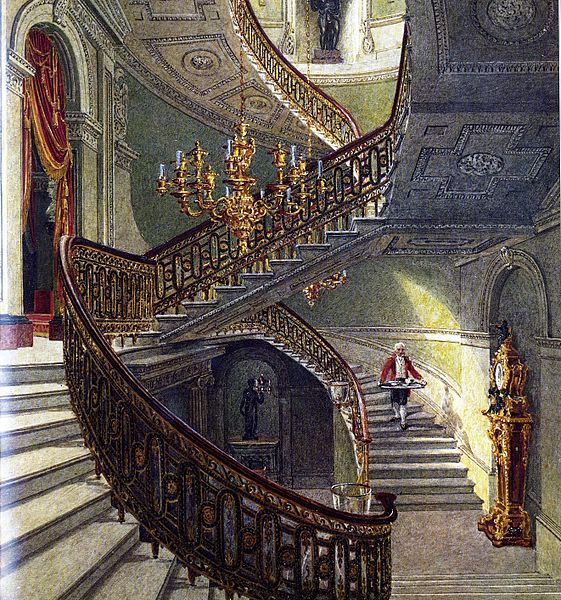

- Romance of London: Carlton House and the Regency

- Romance of London: The Championship at George IV’s Coronation

- Romance of London: Mrs. Cornelys at Carlisle House

- Romance of London: The Bottle Conjuror

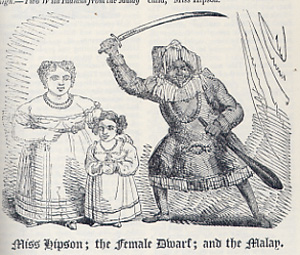

- Romance of London: Bartholomew Fair

- Romance of London: The May Fair and the Strong Woman

- Romance of London: Nancy Dawson, the Hornpipe Dancer

- Romance of London: Milkmaids on May-Day

- Romance of London: Lord Stowell’s Love of Sight-seeing

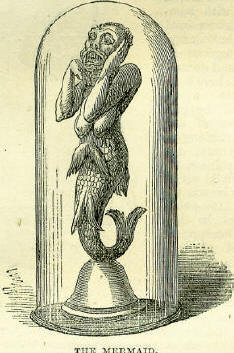

- Romance of London: The Mermaid Hoax

- Romance of London: The Bluestocking and the Sweeps’ Holiday

- Romance of London: Comments on Hogarth’s “Industries and Idle Apprentices”

- Romance of London: The Lansdowne Family

- Romance of London: St. Margaret’s Painted Window at Westminster

- Romance of London: Montague House and the British Museum

- Romance of London: The Bursting of the South Sea Bubble

- Romance of London: The Thames Tunnel

- Romance of London: Sir William Petty and the Lansdowne Family

- Romance of London: Marlborough House and Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough

- Romance of London: The Duke of Newcastle’s Eccentricities

- Romance of London: Voltaire in London

- Romance of London: The Crossing Sweeper

- Romance of London: Nathan Mayer Rothschild’s Fear of Assassination

- Romance of London: Samuel Rogers, the Banker Poet

- Romance of London: The Eccentricities of Lord Byron

- Romance of London: A London Recluse