Romance of London: Strange Stories, Scenes And Remarkable Person of the Great Town in 3 Volumes

John Timbs

John Timbs (1801-1875), who also wrote as Horace Welby, was an English author and aficionado of antiquities. Born in Clerkenwell, London, he was apprenticed at 16 to a druggist and printer, where he soon showed great literary promise. At 19, he began to write for Monthly Magazine, and a year later he was made secretary to the magazine’s proprietor and there began his career as a writer, editor, and antiquarian.

This particular book is available at googlebooks for free in ebook form. Or you can pay for a print version.

The vow of a jester

Rahere, jester to King Henry I

This famous Fair, formerly held every year in Smithfield, at Bartholomewtide [August 24], and within the precinct of the Priory of St. Bartholomew, originated in a grant of land from Henry I., to his jester Rahere, who, disgusted by his manner of living, repented him of his sins, and undertook a pilgrimage to Rome. Here, attacked by sickness, he made a vow, that if he recovered his health, he would found a hospital for poor men. Being reinstated, and on his return to England to fulfill his promise, St. Bartholomew is said to have appeared to him in a vision, and commanded him to found a Church in Smithfield, in his name… The site, which had been previously pointed out in a singular manner to Edward the Confessor, as proper for a house of prayer, was a mere marsh, for the most part covered with water; while on that portion which was not so, stood the common gallows—”the Elms,” in Smithfield, which for centuries after continued to be the place of execution.

The Bartholomew Fair

St. Bartholomew’s Church

The Priory, however, looked to temporal as well as spiritual aid, for his foundation; and therefore, obtained a royal charter to hold a Fair annually at Bartholomewtide, for three days—on the eve, the fête-day of the saint, and the day after; “firm peace,” being granted to all persons frequenting the Fair of St. Bartholomew. This brought traders from all parts, to Smithfield: thither resorted clothiers and drapers, not merely of England, but all countries, who there exposed their goods for sale. The stalls or booths were erected within the walls of the priory churchyard, the gates of which were locked each night, and a watch was set in order to protect the various wares…

At the dissolution of religious houses, the privilege of the Fair was in part transferred to the Mayor and Corporation; and in part to Richard Rich, Lord Rich, who died in 1560, and was ancestor of the Earls of Warwick and Holland. It ceased, however to be a cloth fair of any great importance in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. The drapers of London found another and more extensive market for their woolens; and the clothiers, in the increase of communication between distant places, a wider field for the sale of their manufactures. It subsequently became a Fair of a very diversified character. Monsters, motions, rolls, and rarities were the new attractions to be seen; and the Fair was converted into a kind of London carnival for persons of every condition and degree of life. The Fair was proclaimed by the Lord Mayor, beneath the entrance arch of the priory; and its original connexion with the cloth trade was commemorated in a mock proclamation on the evening before, made by a company of drapers and tailors, who met at the Hand and Shears, a house of call for their fraternity in Cloth Fair, whence they marched and announced the Fair opened and concluded with shouting and the “snapping of shears.”

With respect to the tolls, Strype tells us that “Each person having a booth, paid so much per foot for the first three days. The Earl of Warwick and Holland is concerned in the toll gathered the first three days in the fair, being a penny for each burthen of good brought in or carried out; and to that end there are persons that stand at all the entrances into the Fair…

The Fair lengthens to fourteen days

“In the reign of Charles II., as might be expected, the Fair was extended from three to fourteen days, when all classes, high and low, visited the carnival.” Pepys mentioned walking up and down the fair grounds on August 30, 1667, and discovering Lady Castlemaine at a puppet-play, “and the street full of people, expecting her coming out.” In 1668, Pepys went to the fair “to see the mare that tells money, and many things to admiration, and then the dancing of the ropes, and also the Irish stage play, which is very ridiculous.”

(c) Dover Collections; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

Theatrical booths were very popular. “Ben Jonson, the actor (says Dr. Rimbault), was connected with the booth before 1694, in which year he joined Cibber’s company; he was celebrated as the grave-digger in Hamlet…

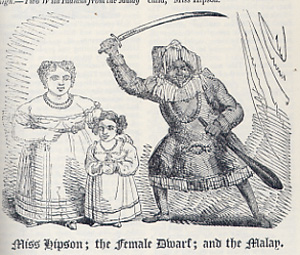

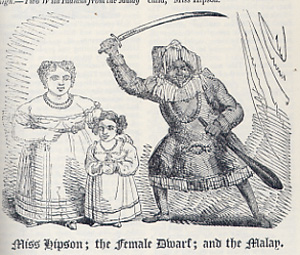

Here were motions or puppet-shows of Jerusalem, Nineveh, and Norwich; and the Gunpowder Plot played nine times in an afternoon; wild beasts, dwarfs, and other monstrosities; operas and tight-rope-dancing and sarabands [dances]; dogs dancing the morris; the hare beating the tabor; and rolls of every degree.

Bartholomew Fair 1825

From a newspaper in 1734:

At Goodwin’s Large Theatrical Booth, opposite the White Hart, in West Smithfield, near Cow Lane, the town will be entertained with a humorous Comedy of three acts, called ‘The Intriguing Footman, or the Spaniard Outwitted;’ with a Pantomime entertainment of Dancing, between a Soldier and a Sailor, and a Tinker and a Tailor, and Buxom Joan of Deptford.

At Hippisley and Chapman’s Great Theatrical Booth, in the George Inn Yard, Smithfield, the town will be humorously diverted with an excellent entertainment; Signor Arthurian, who has a most surprising talent at grimace, and will, on this occasion, introduce upwards of fifty whimsical, sorrowful, comical, and diverting faces.”

The fourteen days were found too long, for the excesses committed were very great; and in the year 1708, the period of the Fair was restricted to its old duration of three days.

Hogarth 1733

Three days of revelry

The influence of the fair in the neighborhood was to make general holiday… We read that in Little Britain, “during the time of the Fair, there was nothing going on but gossiping and gadding about. The still quiet streets of Little Britain were overrun with an irruption of strange figures and faces; every tavern was a scene of rout and revel. The fiddle and the song are heard from the taproom, morning, noon, and night; and at each window might be seen some group of loose companions, with half-shut eyes, hats on one side, pipe in mouth, tankard in hand, fondling, and prosing, and singing maudlin songs over their liquor. Even the sober decorum of private families was no proof against this saturnalia. There was no such thing as keeping maid-servants within doors. Their brains were absolutely set maddening with Punch and the puppet-show; the flying horses; Signior Polito; the Fire-eater, the celebrated Mr. Paap; and the Irish Giant. The children, too, lavished all their holiday-money in toys and gilt gingerbread, and filled the house with the Lilliputian din of drums, trumpets, and penny whistles.”

Bartholomew Fan

The end of Bartholomew Fair

The Lord Mayor and Aldermen had, for 300 years, tried by orders, proclamations, juries, and presentments to abolish the Fair, but without effect; when the Court of Common Council took the work in hand. Having obtained entire control over the Fair by the purchase of Lord Kensington’s interest, they refused to let standings for shows and booths; they prevailed upon the Lord Mayor and Sheriffs to give up the practice of going to open the Fair in state, with a herald to proclaim it, and officers to marshal the procession; the posting of the proclamation about the streets, interdicting rioting and debauchery during the days of the Fair and within its precincts, were discontinued… In 1852, not a single show was to be seen on the ground; and in 1855 the Fair expired… and Bartholomew Fair was extinct.

Author’s Note: I’m thinking of having my Regency characters attend the fair, even though it was rather scandalous. What do you think?

Romance of London Series

- Romance of London: The Lord Mayor’s Fool… and a Dessert

- Romance of London: Carlton House and the Regency

- Romance of London: The Championship at George IV’s Coronation

- Romance of London: Mrs. Cornelys at Carlisle House

- Romance of London: The Bottle Conjuror

- Romance of London: Bartholomew Fair

- Romance of London: The May Fair and the Strong Woman

- Romance of London: Nancy Dawson, the Hornpipe Dancer

- Romance of London: Milkmaids on May-Day

- Romance of London: Lord Stowell’s Love of Sight-seeing

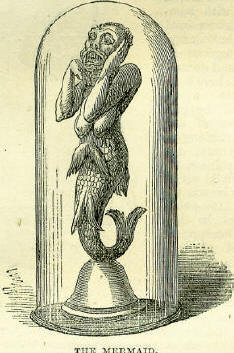

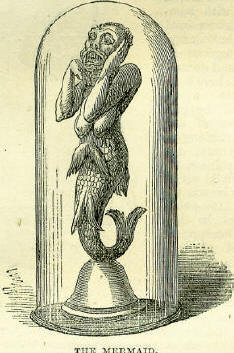

- Romance of London: The Mermaid Hoax

- Romance of London: The Bluestocking and the Sweeps’ Holiday

- Romance of London: Comments on Hogarth’s “Industries and Idle Apprentices”

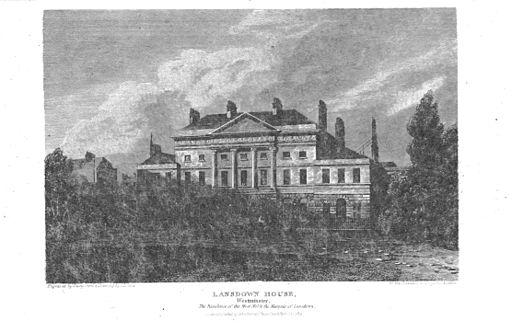

- Romance of London: The Lansdowne Family

- Romance of London: St. Margaret’s Painted Window at Westminster

- Romance of London: Montague House and the British Museum

- Romance of London: The Bursting of the South Sea Bubble

- Romance of London: The Thames Tunnel

- Romance of London: Sir William Petty and the Lansdowne Family

- Romance of London: Marlborough House and Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough

- Romance of London: The Duke of Newcastle’s Eccentricities

- Romance of London: Voltaire in London

- Romance of London: The Crossing Sweeper

- Romance of London: Nathan Mayer Rothschild’s Fear of Assassination

- Romance of London: Samuel Rogers, the Banker Poet

- Romance of London: The Eccentricities of Lord Byron

- Romance of London: A London Recluse

The well known “Adam style” is said to have begun with Syon House. It was commissioned to be built in the Neo-classical style, which was fulfilled, but Adam’s eclectic style doesn’t end there. Syon is filled with multiple styles and inspirations including a huge influence of Roman antiquity, highly visible Romantic, Picturesque, Baroque and Mannerist styles and a dash of Gothic. There is also evidence in his decorative motifs of his influence by Pompeii that he received while studying in Italy. Adam’s plan of Syon House included a complete set of rooms on the main floor, a domed rotunda with a circular inner colonnade meant for the main courtyard (‘meant for’ meaning that this rotunda was not built due to a lack of funds), five main rooms on the west, east and south side of the building, a pillared ante-room famous for its colour, a Great Hall, a grand staircase (though not built as grand as originally designed) and a Long Gallery stretching 136 feet long. Adam’s most famous addition is the suite of state rooms and as such they remain exactly as they were built.

The well known “Adam style” is said to have begun with Syon House. It was commissioned to be built in the Neo-classical style, which was fulfilled, but Adam’s eclectic style doesn’t end there. Syon is filled with multiple styles and inspirations including a huge influence of Roman antiquity, highly visible Romantic, Picturesque, Baroque and Mannerist styles and a dash of Gothic. There is also evidence in his decorative motifs of his influence by Pompeii that he received while studying in Italy. Adam’s plan of Syon House included a complete set of rooms on the main floor, a domed rotunda with a circular inner colonnade meant for the main courtyard (‘meant for’ meaning that this rotunda was not built due to a lack of funds), five main rooms on the west, east and south side of the building, a pillared ante-room famous for its colour, a Great Hall, a grand staircase (though not built as grand as originally designed) and a Long Gallery stretching 136 feet long. Adam’s most famous addition is the suite of state rooms and as such they remain exactly as they were built. More specific to the interior of Adam’s rooms is where the elaborate detail and colour shines through. Adam added detailed marble chimneypieces, shuttering doors and doorways in the Drawing Room, along with fluted columns with Corinthian capitals. The long gallery, which is about 14 feet high and 14 feet wide, contains many recesses and niches into the thick wall for books along with rich and light decoration and stucco-covered walls and ceiling. At the end of the gallery is a closet with a domed circle supported by eight columns; halfway through the columns is a doorway imitating a niche.

More specific to the interior of Adam’s rooms is where the elaborate detail and colour shines through. Adam added detailed marble chimneypieces, shuttering doors and doorways in the Drawing Room, along with fluted columns with Corinthian capitals. The long gallery, which is about 14 feet high and 14 feet wide, contains many recesses and niches into the thick wall for books along with rich and light decoration and stucco-covered walls and ceiling. At the end of the gallery is a closet with a domed circle supported by eight columns; halfway through the columns is a doorway imitating a niche.