Eight authors and eight different takes on four dramatic elements selected by our readers—an older heroine, a wise man, a Bible, and a compromising situation that isn’t.

Set in a variety of locations around the world over eight centuries, welcome to the romance of the Bluestocking Belles’ 2017 Holiday and More Anthology.

Special Pre-order Sale just $0.99

After November 15th: $2.99

We’re still working on the rest of the retailer links but just in case you want to take advantage of our special pre-order price, jump on over to Amazon and order your copy now. The release date for NEVER TOO LATE is November 4th. Remember, 25% of the sales from the Belles’ box sets benefit our mutual charity, The Malala Fund. You, too, can make a difference in the life of a young woman or child by contributing to this worthy cause!

Amazon:

US: http://amzn.to/2y6oBg7

AU: http://amzn.to/2fycyAx

BR: http://amzn.to/2wjyWkm

CA: http://amzn.to/2yFvxxS

DE: http://amzn.to/2xA0Udb

ES: http://amzn.to/2yFIgk4

FR: http://amzn.to/2yF7gbg

IN: http://amzn.to/2fzQkhv

IT: http://amzn.to/2xzPPbW

JP: http://amzn.to/2xK5yqS

MX: http://amzn.to/2xJTlCK

NL: http://amzn.to/2hvRYkV

UK: http://amzn.to/2fyBesx

iBooks:

http://apple.co/2yY4gXC

Kobo:

http://bit.ly/2fK7vJR

Nook:

http://bit.ly/2y63988

Smashwords:

http://bit.ly/2xDMQkb

Print – $18.99

http://amzn.to/2zQ36Ny

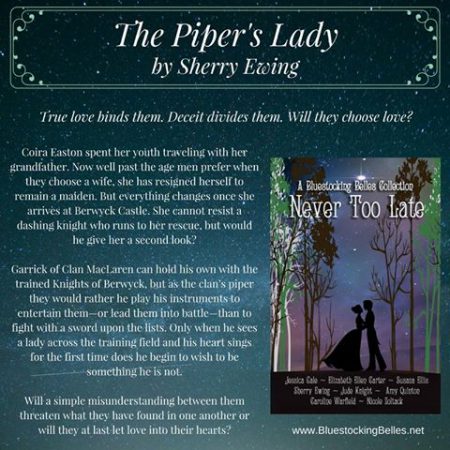

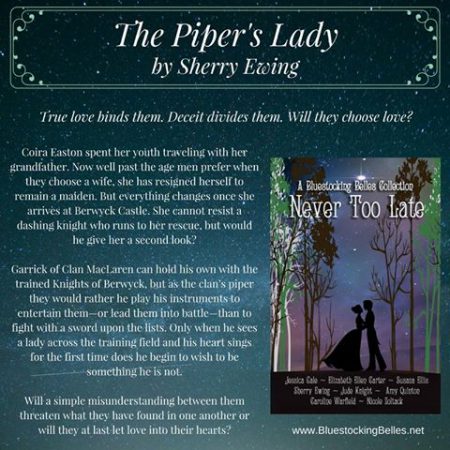

The Piper’s Lady by Sherry Ewing

True love binds them. Deceit divides them. Will they choose love?

Coira does not regret traveling with her grandfather until she is too old to wed. But perhaps it is not too late? At Berwyck Castle, a dashing knight runs to her rescue. How can she resist?

Garrick can hold his own with the trained Knights of Berwyck, but they think of him as a piper, not a fighter. When his heart sings for the new resident of the castle, he dares to wish he is something he is not. Will failure to clear her misunderstanding doom their love before it begins?

Excerpt

“You saved me,” she whispered in a shaky tone. “You are truly a gallant knight to rescue me. Your liege lord must value you as one of his warriors.”

Warrior? Him? He opened his mouth to correct her assumption but could not find the words. He knew she would think less of him if she but knew he was only the clan’s piper.

“Are ye harmed?” he murmured, still holding the pleasing womanly curves of the lady who had not yet moved from atop him. Her brow rose, and Garrick inwardly cursed knowing there was no way to hide his Scottish accent.

“Nay, but only because of your ability to move so quickly. Thank you, Sir…” She left her sentence linger in the air between them.

“Garrick,” he answered, giving her his name, “of Clan MacLaren.”

“My thanks, Sir Garrick,” she replied with a kind smile.

They seemed to come to the realization the lists had become eerily silent with the exception of one person running in their direction.

“Get your hands off her!” a voice bellowed.

Before either of them could move, the woman was ripped from his arms, and Garrick saw her enveloped in the fierce embrace of Morgan. Her arms wrapped around his neck, and Garrick could not help the feeling of jealousy assaulting his emotions and tugging at his heartstrings.

“Coira! By St. Michael’s Wings you gave me such a fright, woman,” Morgan scolded in concern. Setting her down upon her feet, he proceeded to clasp both her cheeks afore placing kisses on each.

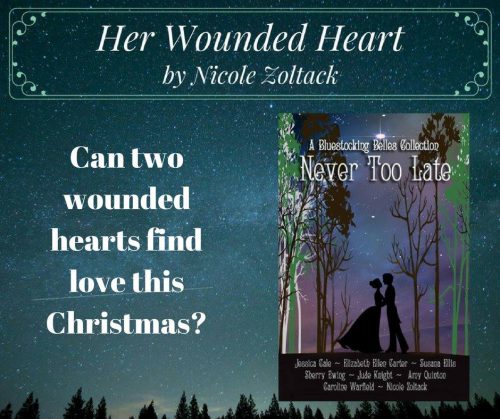

Her Wounded Heart by Nicole Zoltack

An injured knight trespassing on Mary Bennett’s land is a threat to the widow’s

already frail refuge. Even so, she cannot turn away a man in need and tells him he has her husband’s leave to stay until Christmas.

Doran Ward wishes only to survive for one more day. However, as he begins to

heal and to pay for his lodgings by fixing the rundown manor, the wounds to Mistress Bennett’s heart intrigue him.

Can two desperate souls find hope in time for Christmas?

Excerpt

To her surprise, her guest had laid out a few vegetables, and she set about cutting them without saying a word to him.

At one point, he reached across her for another knife.

She stiffened and jerked back.

“My apologies,” he said. “I did not mean to startle you.”

“Do not touch me,” she said, fear melting into anger in her voice. “My husband is a very strong and angry man. He shall take exception to anyone who dares to touch me.”

“Will he be joining us for dinner?” he asked as if unfazed.

She did not like to lie to him. Lying, after all, was a sin. But she also must protect herself.

“No,” she said shortly. “He already ate and has retired for the evening.”

“So it shall be only the two of us?” He glanced over his shoulder at the chunks of meat he had cooking over the fierce fire.

“Aye. You can brine-cure the meat we do not eat.”

“Very well.” He never did grab the knife but returned to tending to the meat.

Soon enough, she added the vegetables to a pot, along with some of his meat. A short time later, the stew was finished.

The man brought over two bowls. She stared at the wooden spoons in her hands. Her husband had lost their silver in yet another game.

Another sign to alert him that all is not well here.

Head back, she took a deep breath. Matters such as they were, she had no other recourse. As cold as the house was despite fires, she could not imagine anyone surviving the night out of doors. Would her good intentions spell even more doom for herself?

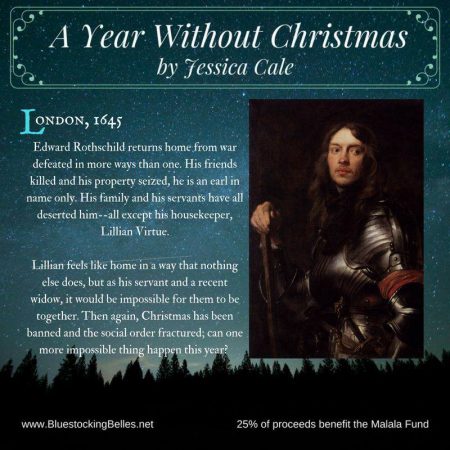

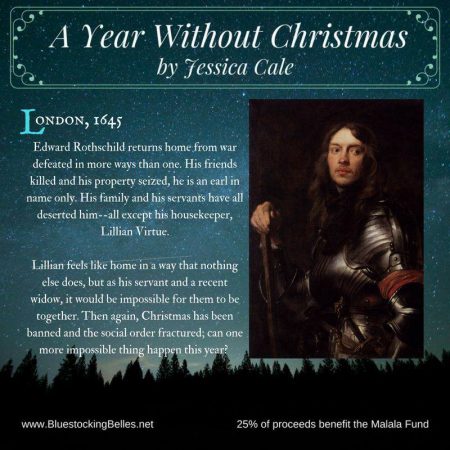

A Year Without Christmas by Jessica Cale

London, 1645

Edward Rothschild returns home from war defeated in more ways than one. His friends killed and his property seized, he is an earl in name only. His family and his servants have all deserted him– all except his housekeeper, Lillian Virtue.

Lillian feels like home in a way that nothing else does, but as his servant and a recent widow, it would be impossible for them to be together. Then again, Christmas has been banned and the social order fractured; can one more impossible thing happen this year?

Excerpt

Somerton’s smile was like a bolt of lightning, a sudden flash of terrifying intensity that surprised them both. One shot of light across the darkness of his face and it was gone.

Her knees failed her suddenly and Lillian caught herself on the edge of the table just as Somerton reached out to catch her arm. His hand closed around her elbow and sent a shock up her spine.

“Are you well?”

Lillian had always held her master in the highest regard, but some part of her had feared him, as well. It was not only that her position depended upon his good graces, but he had seemed more than human to her. His presence was overwhelming and perhaps otherworldly; he had a spark of the infinite that suggested a link to the Divine. She could have easily taken him for a priest or a saint.

She had known he was objectively handsome; what she had not realized was that she thought he was handsome.

She felt her blush deepen and took a steadying breath. “Quite well, my lord. Forgive me.”

He frowned as he examined her face. “You look peaked. Join me for coffee.”

Somerton wanted her—Lillian Page, no, Virtue—to sip coffee with him in his private bedchamber? It was inappropriate, to say the least, but when she opened her mouth to object, all that came out was, “I only brought one cup.”

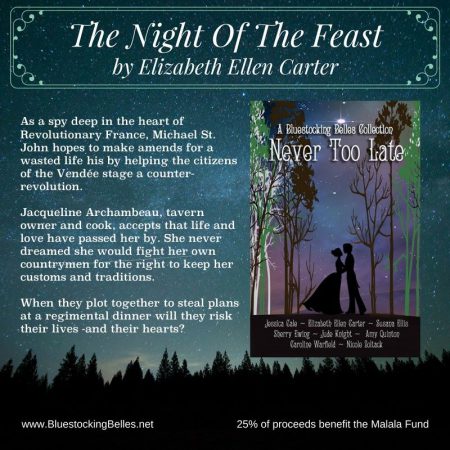

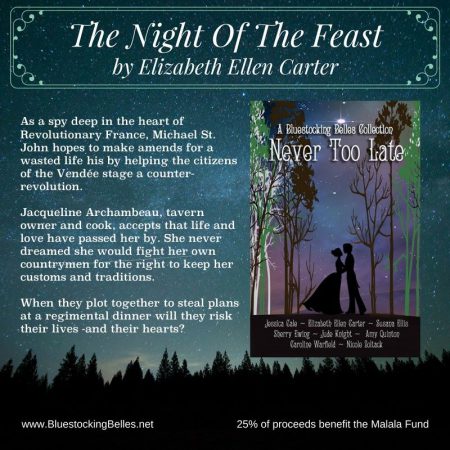

The Night of the Feast by Elizabeth Ellen Carter

As a spy deep in the heart of Revolutionary France, Michael St. John hopes to make amends for a wasted life his by helping the citizens of the Vendée stage a counter-revolution.

Jacqueline Archambeau, tavern owner and cook, accepts that life and love have passed her by. She never dreamed she would fight her own countrymen for the right to keep her customs and traditions.

When they plot together to steal plans at a regimental dinner will they risk their lives—and their hearts?

Excerpt

“Bonjour.” The smile on Jacqueline’s face was unexpected, as was the greeting and he found himself returning it.

Until he felt the unmistakable press of a gun barrel at his lower back. It seemed that Madame Jacqueline was not alone.

“Your knife, monsieur.” Jacqueline held out her hand.

Michael obliged, handing the weapon over hilt first.

“So, Jacques is really Jacqueline?” he asked, feeling like the world’s greatest fool.

“And I’ll take any other weapons you might have on your person,” she continued.

He hesitated, and the barrel pressed at his back became silently insistent.

“Please?” she asked as pleasantly as if she had simply asked him to pass the butter.

Michael raised his arms, threaded his fingers, and placed them at the back of his head.

“You’ve completely disarmed me, madam, but you are welcome to check for yourself.”

Hazel eyes clouded with mistrust. Jacqueline glanced to the person behind him as though looking for instruction.

“Who sent you?”

The voice behind him was that of another woman.

Michael gritted his teeth. He would kill Colonel Jeffers when they next met. The man knew his contacts were women and thought it amusing not to tell him. To further his bona fides, Jeffers had even made him memorize the first stanza of a poem, Ode To Him Who Complains, no less, by scandalous poetess Mary Darby Robinson.

The Umbrella Chronicles: George & Dorothea’s Story

by Amy Quinton

Lord George St. Vincent doesn’t realize it, but his days as a bachelor in good standing are numbered.

He has a fortnight, to be precise—the duration of the Marquess of Dansbury’s house party.

For I, Lady Harriett Ross, have committed to parting with several items of sentimental worth should I fail to orchestrate his downfall—er, betrothal—to Miss Dorothea Wythe, who is delightful, brilliant, and interested (or will be).

If I have anything to say about matters, and I always have something to say about matters, they’re both doomed.

Did I say doomed? I mean, destined—for a life filled with love.

Excerpt

Without a doubt, he made her breath catch every single time he looked her way, even if only looking past her, which was pretty much all the time and kind of pitiful. But who cared? It was another secret that was all hers.

Besides, she was undoubtedly not the only woman who struggled to breathe in his presence.

Dory clenched her hands into fists and reminded herself for the millionth time that she was more of the glasses and books type (of which there were far too few in the world) than the roguish smile and flirty type (of which far too many abounded). Hence, her easy slide into spinsterhood at the ripe age of thirty-one.

Yes. St. George was blond and slender and solidly built. And he was beautiful, somehow elegantly masculine, and gloriously tall. She wasn’t the only person that understood this. Everyone acknowledged these traits as if they were all a set of facts that could be found in any book on science. Or a math fact, a proven geometrical theorem.

Like the bluestocking she was, Dory imagined writing proofs over the theory of his gentlemanly beauty. Given George St. Vincent is taller than most men. Given St. Vincent has blue eyes the color of the sky and blonde hair the color of wheat. Given George St. Vincent has a blinding smile and broad shoulders. Prove George St. Vincent is the most swoonworthy man in all of England.

Dory chuckled to herself, though she felt on the verge of hysterics.

But all of that didn’t mean he was a worthy man for her affections.

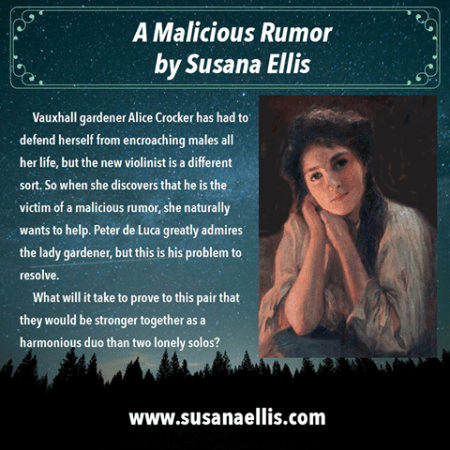

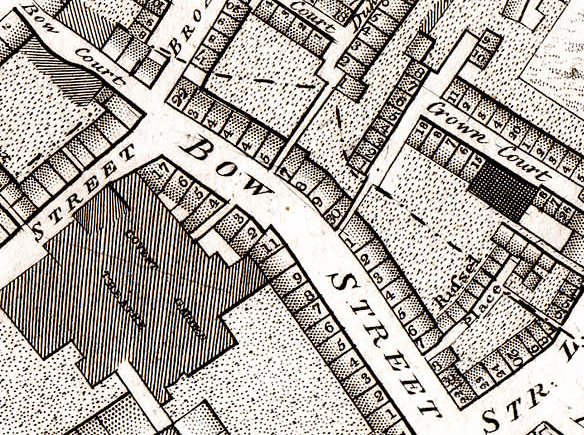

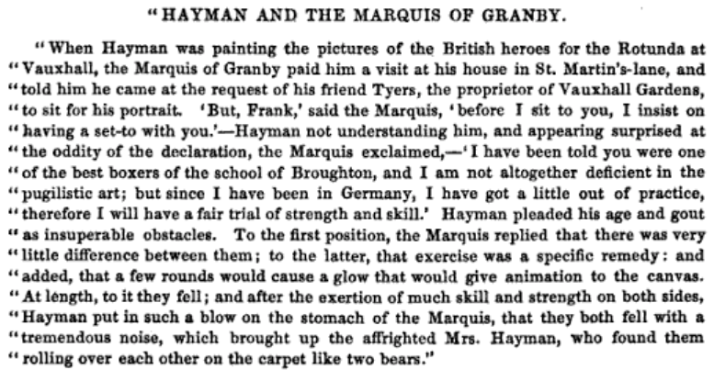

A Malicious Rumor by Susana Ellis

Vauxhall gardener Alice Crocker has had to defend herself from encroaching males all her life, but the new violinist is a different sort. So when she discovers that he is the victim of a malicious rumor, she naturally wants to help.

Peter de Luca greatly admires the lady gardener, but this is his problem to resolve.

What will it take to prove to this pair that they would be stronger together as a harmonious duo than two lonely solos?

Excerpt

Alice found her feet tapping in time to the music of the orchestra rehearsal while she inspected the site for the new illumination, which would honor the new Duke of Wellington after his victory over Bonaparte at the Battle of Paris. If only the designer had included the measurements! It was difficult to decide how to arrange the plantings without some inkling of the space requirements. With luck, the fellow himself would arrive soon, since the spectacle was planned to open the next day.

Miss Stephens must be singing tonight, she thought as she found herself humming the tune of the popular Northumberland ballad about a brave lass who rowed out in a storm to save her shipwrecked sailor beau.

O! merry row, O! merry row the bonnie, bonnie bark,

Bring back my love to calm my woe,

Before the night grows dark.

She liked the idea of a woman rescuing her man instead of the other way around. It might seem romantic to be rescued by a handsome prince, but one could not always be a damsel in distress, could one? Alice knew from her mother’s marriage that there was no happiness or romance in a marriage where one partner held all the power. She herself had no intention of placing herself in the power of any man. She would be responsible to no one but herself—and perhaps her employer, as long as she was permitted to work for a living. She narrowed her eyes. She could work as well as any man, better than some, in fact. Why did so many men feel threatened by that?

Forged in Fire by Jude Knight

Burned in their youth, neither Tad nor Lottie expected to feel the fires of love. The years have soothed the pain, and each has built a comfortable, if not fully satisfying, life, on paths that intersect and then diverge again.

But then the inferno of a volcanic eruption sears away the lies of the past and frees them to forge a future together.

Excerpt

She was nothing to him. He was sorry for her, that was all. As he’d be sorry for anyone stuck in her predicament. She’d be better off staying in New Zealand, where Mrs. Bletherow’s malice couldn’t reach her. There was work in Auckland, in shops and factories. Not that a proper English lady would consider such a thing.

She could do it, though. She wasn’t as meek as she pretended. He’d seen the steel in her, the fire in those pretty hazel eyes.

The word ‘pretty’ put a check in his stride, but it was true. She had lovely eyes. Not a pretty face, precisely. Her cheeks were too thin, her jaw too square, her nose too straight for merely ‘pretty’. But in her own way, she was magnificent. She was not as comfortably curved or as young as the females he used to chase when he was a wild youth, the sort he always thought he preferred. Not as gaudy as them, with their bright dresses and their brighter face paint. But considerably less drab than he had thought at first sight. She was a little brown hen that showed to disadvantage beside the showier feathers of the parrot, but whose feathers were a subtle symphony of shades and patterns. Besides, parrots, in his experience, were selfish, demanding creatures.

Roses in Picardy by Caroline Warfield

After two years at war, Harry is out of metaphors for death, synonyms for brown, and images for darkness. Color among the floating islands of Amiens and life in the form of a widow and her little son surprise him with hope.

Rosemarie Legrand’s husband died, leaving her a tiny son, no money, and a savaged reputation. She struggles to simply feed the boy and has little to offer a lonely soldier.

Excerpt

Are men in Hell happier for a glimpse of Heaven?”

The piercing eyes gentled. “Perhaps not,” the old man said, “but a store of memories might be medicinal in coming months. Will you come back?”

Will I? He turned around to face forward, and the priest poled the boat out of the shallows, seemingly content to allow him his silence.

“How did you arrange my leave?” Harry asked at last, giving voice to a sudden insight.

“Prayer,” the priest said. Several moments later he, added, “And Col. Sutherland in the logistics office has become a friend. I suggested he had a pressing need for someone who could translate requests from villagers.”

“Don’t meddle, old man. Even if they use me, I’ll end up back in the trenches. Visits to Rosemarie Legrand would be futile in any case. The war is no closer to an end than it was two years ago.”

“Despair can be deadly in a soldier, corporal. You must hold on to hope. We all need hope, but to you, it can be life or death,” the priest said.

Life or death. He thought of the feel of the toddler on his shoulder and the colors of les hortillonnages. Life indeed.

The sound of the pole propelling them forward filled several minutes.

“So will you come back?” the old man asked softly. He didn’t appear discomforted by the long silence that followed.

“If I have a chance to come, I won’t be able to stay away,” Harry murmured, keeping his back to the priest.

“Then I will pray you have a chance,” the old man said softly.