Romance of London: Strange Stories, Scenes And Remarkable Person of the Great Town in 3 Volumes

John Timbs

John Timbs (1801-1875), who also wrote as Horace Welby, was an English author and aficionado of antiquities. Born in Clerkenwell, London, he was apprenticed at 16 to a druggist and printer, where he soon showed great literary promise. At 19, he began to write for Monthly Magazine, and a year later he was made secretary to the magazine’s proprietor and there began his career as a writer, editor, and antiquarian.

This particular book is available at googlebooks for free in ebook form. Or you can pay for a print version.

Comments on Hogarth’s “Industrious and Idle Apprentices”

Mr. Thackeray, in his Lectures on the English Humorists, thus vividly paints the scenes of Hogarth’s masterpieces; at the same time he very ingeniously contrasts the past with the present—one of the more immediate benefits of the Lecture: the past is generally interesting, but it chiefly becomes instructive when brought under the powerful focus of the present. His account of Hogarth’s “Apprentices” is a masterpiece in this way:

Fair-haired Frank Goodchild smiles at his work, whilst naughty Tom Idle snores over his loom. Frank reads the edifying ballads of Whittington and the London ‘Prentice: whilst that reprobate Tom Idle prefers Moll Flanders, and drinks hugely of beer.

William Hogarth-industry and idleness plate 2 the industrious prentice_performing the duty of a Christian

Frank goes to church on a Sunday, and warbles hymns from the gallery; while Tom lies on a tomb-stone outside playing at halfpenny-under-the-hat, and with street blackguards, and deservedly caned by the beadle.

william hogarth -industry and idleness plate 3 the idle prentice at play in the church yard during divine service

Frank is made overseer of the business; whilst Tom is sent to sea.

William_Hogarth Industry and Idleness, Plate 4; The Industrious ‘Prentice a Favourite, and entrusted by his Master

Frank is taken into partnership, and marries his master’s daughter, sends out broken victuals to the poor, and listens in his night-cap and gown with the lovely Mrs. Goodchild by his side, to the nuptial music of the city bands and the marrow-bones and cleavers; whilst idle Tom, returned from sea, shudders in a garret lest the officers are coming to take him for picking pockets.

william hogarth – industry and idleness plate 6 the industrious prentice out of his time married to his masters daughter

william hogarth – industry and idleness plate 7 the idle prentice returnd from sea in a garret with common prostitute

The Worshipful Francis Goodchild, Esq., becomes Sheriff of London, and partakes of the most splendid dinners which money can purchase or alderman devour; whilst poor Tom is taken up in a night cellar, with that one-eyed and disreputable accomplice who first taught him to play chuck-farthing on a Sunday.

william hogarth – industry and idleness plate 8 the industrious prentice grown right sheriff of london

What happens next? Tom is brought up before the justice of his county, in the person of Mr. Alderman Goodchild, who weeps as he recognizes his old brother ‘prentice, as Tom’s one-eyed friend peaches on him, as the clerk makes out the poor rogue’s ticket for Newgate.

william hogarth – industry and idleness plate 9 the idle prentice betrayed and taken in a night-cellar with his accomplice

william hogarth -industry and idleness plate 10 the industrious prentice alderman of_london the idle on brought before him impreachd by his accomplice

Then the end comes. Tom goes to Tyburn in a cart with a coffin in it; whilst the right Honorable Francis Goodchild, Lord Mayor of London, proceeds to his Mansion House, in his gilt coach, with four footmen and a sword-bearer, whilst the companies of London march in the august procession, whilst the train-bands of the city fire their pieces and get drunk in his honor; and oh, crowning delight and glory of all, whilst his majesty the king looks out of his royal balcony, with his ribbon on his breast, and his queen and his star by his side at the corner house of St. Paul’s Church-yard, where the toy-shop is now.

How the times have changed! The new Post-office now not disadvantageously occupies that spot where the scaffolding is on the picture, where the tipsy trainband-man is lurching against the post, with his wig over one eye, and the ‘prentice-boy is trying to kiss the pretty girl in the gallery. Past away ‘prentice boy and pretty girl! Past away tipsy trainband-man with wig and bandolier! On the spot where Tom Idle (for whom I have an unaffected pity) made his exit from this wicked world, and where you see the hangman smoking his pipe, as he reclines on the gibbet, and views the hills of Harrow on Hampstead beyond—a splendid marble arch, a vast and modern city—clean, airy, painted drab, populous with nursery-maids and children, the abodes of wealth and comfort—the elegant, the prosperous, the polite Tyburnia rises, the most respectable district in the habitable globe!

In that last plate of the London Apprentices, in which the apotheosis of the Right Honorable Francis Goodchild is drawn, a ragged fellow is represented in the corner of the simple kindly piece, offering for sale a broadside, purporting to contain an account of the appearance of the ghost of Tom Idle, executed at Tyburn. Could Tom’s ghost have made its appearance in 1847, and not in 1747, what changes would have been remarked by that astonished escaped criminal! Over that road which the hangman used to travel constantly, and the Oxford stage twice a week, go ten thousand carriages every day; over yonder road, by which Dick Turpin fled to Windsor, and Squire Western journeyed into town, when he came to take up his quarters at the Hercules Pillars not he outskirts of London, what a rush of civilization and order flows now! What armies of gentlemen with umbrellas march to banks, and chambers, and counting-houses! What regiments of nursery-maids and pretty infantry: what peaceful processions of policemen, what light broughams and what gay carriages, what swarms of busy apprentices and artificers, riding on omnibus-roofs, pass daily and hourly! Tom Idle’s times are quite changed; many of the institutions gone into disuse which were admired in his day. There’s more pity and kindness, and a better chance for poor Tom’s successors now than at that simpler period, when Fielding hanged him, and Hogarth drew him.

One hundred and fifty years after Thackeray’s assertions that the world is a kinder place toward kids like Idle Tom, I’m not so certain I can say the same. As a former teacher, it seems to me that the system is still stacked against kids who “dance to a different drum” or who are raised in poverty and/or by indifferent parents. And I’ll be damned if I know how to change that. What do you think?

Romance of London Series

- Romance of London: The Lord Mayor’s Fool… and a Dessert

- Romance of London: Carlton House and the Regency

- Romance of London: The Championship at George IV’s Coronation

- Romance of London: Mrs. Cornelys at Carlisle House

- Romance of London: The Bottle Conjuror

- Romance of London: Bartholomew Fair

- Romance of London: The May Fair and the Strong Woman

- Romance of London: Nancy Dawson, the Hornpipe Dancer

- Romance of London: Milkmaids on May-Day

- Romance of London: Lord Stowell’s Love of Sight-seeing

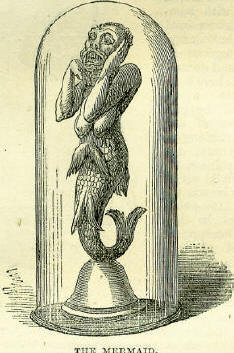

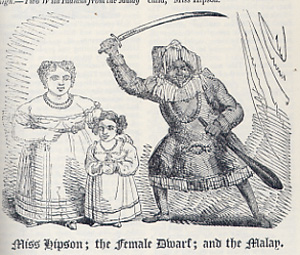

- Romance of London: The Mermaid Hoax

- Romance of London: The Bluestocking and the Sweeps’ Holiday

- Romance of London: Comments on Hogarth’s “Industries and Idle Apprentices”

- Romance of London: The Lansdowne Family

- Romance of London: St. Margaret’s Painted Window at Westminster

- Romance of London: Montague House and the British Museum

- Romance of London: The Bursting of the South Sea Bubble

- Romance of London: The Thames Tunnel

- Romance of London: Sir William Petty and the Lansdowne Family

- Romance of London: Marlborough House and Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough

- Romance of London: The Duke of Newcastle’s Eccentricities

- Romance of London: Voltaire in London

- Romance of London: The Crossing Sweeper

- Romance of London: Nathan Mayer Rothschild’s Fear of Assassination

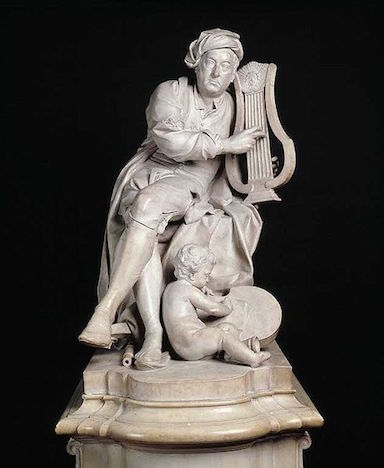

- Romance of London: Samuel Rogers, the Banker Poet

- Romance of London: The Eccentricities of Lord Byron

- Romance of London: A London Recluse