published by Rudolph Ackermann in 3 volumes, 1808–1811.

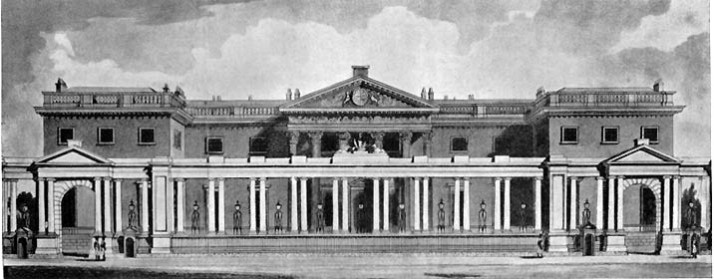

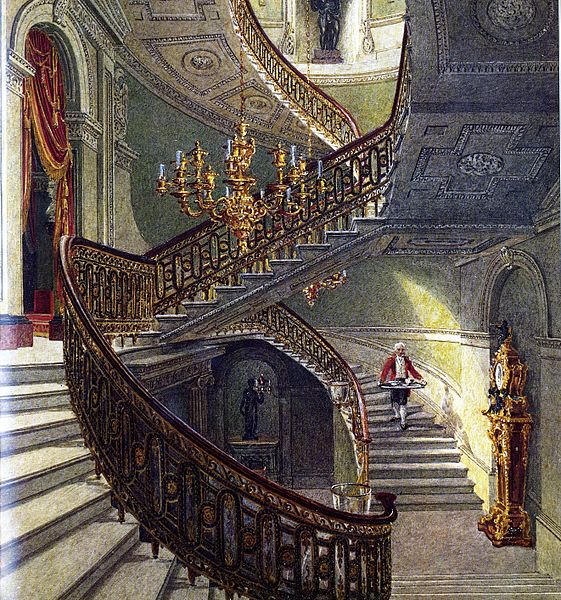

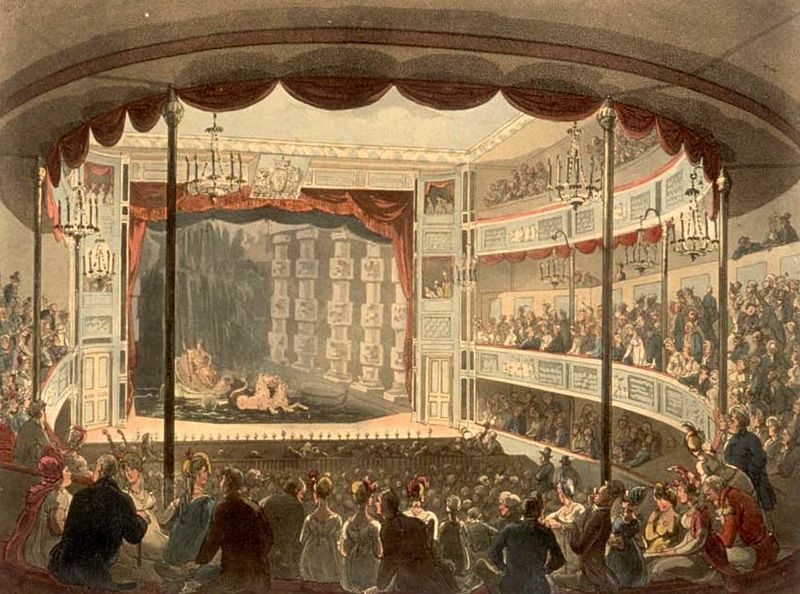

The annexed print is a view of the great hall, which is conceived with a classic elegance, that does honour to the genius of the late Mr. Holland, who was the architect of Carlton House. The size of the hall is forty-four feet in length and twenty-nine in breadth. The entrance to the hall from the vestibule is by a flight of steps, which gives it an air of uncommon grandeur; it is supported by eight fine columns of the Ionic order, with architrave, frieze, and cornice. The ceiling is coved, and ornamented with plain caissons, and lighted by a skylight of an oval form. The columns are finely executed in scaglioni, of a yellow porphyry; the capitals and bases are bronzed, as are all the ornaments in the hall. In four corresponding niches are casts from the antique, of two Muses, the Antinous and the Discobulus; on the cornice are placed busts, urns, and griffins; over the niches are basso-relievos, which are also bronzed. At each . end of the hall is a stove of a new and elegant construction; six Termini of fine workmanship support a dome or canopy: the whole is executed in cast-iron bronzed. Over each fire-place is an allegorical painting in imitation of bronze basso-relievo, and compartments over the doors in the same manner: the tout-ensemble is striking and impressive. There is in this hall a symmetry and proportion, a happy adjustment of the parts to produce a whole, that are rarely seen; it is considered as the chef d’ oeuvre of Mr. Holland, and would do honour to any architect of any age or country.

Of the print it may be proper to say, that it is drawn with great accuracy and feeling, the perspective is easy and natural, and the general effect broad and simple. The figures are few, but introduced with great taste: it must be obvious, that a greater number would have impaired the general effect of the architectural design.

The new circular dining-room, when completed, will unquestionably be one of the most splendid apartments in Europe: the walls are entirely covered with silver, on which are painted Etruscan ornaments in relief, with vine-leaves, trellis-work, &c. There are eight fine Ionic columns in scaglioni, of red granite; the capitals and bases are silver, as are also the enrichments, moulding. See. of the architrave, frieze, and cornice: the latter is surmounted by an ornament that is somewhat Turkish in its character, and which, if it does not belong to the Ionic order, nevertheless adds to the splendour of the room. There are four immense pier glasses, and under each of them a fine marble chimney-piece of exquisite workmanship. As this sumptuous apartment is not yet completed, it would be improper to attempt a perfect description of it; indeed, almost the whole of Carlton House is undergoing alterations and improvements. On the south side of this apartment a door opens into the ballroom, a most magnificent and princely apartment: the walls are painted white, but the room is nearly covered with a profusion of gilding; the pilasters, architrave, frieze, and cornice are all covered with gold; the ceiling represents a pleasing sky, in which are genii sporting on the clouds; and in the compartments between the pilasters are some Etruscan ornaments, painted with great lightness and delicacy. On the opposite side another door opens into a new room, intended for a drawing-room, and though at present in a very unfinished state, it strikes the eye with the uncommon symmetry and harmony of its proportions.

Amid the curiosity and interest raised by a view of Carlton House, nothing can exceed that which is excited by an examination of

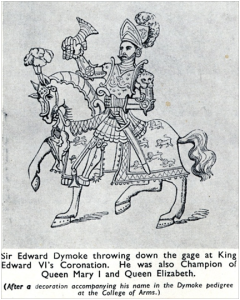

The Armory

This valuable and unique collection is a museum, not of arms only, but of various works of art, dresses, &c.: it is arranged with great order, skill, and taste, under the immediate inspection of His Royal Highness. It occupies five rooms on the attic story; the swords, firearms, &c. are disposed in various figures upon scarlet cloth, and inclosed in glass cases: the whole is kept in a state of the most perfect brightness. Here are swords of every country, many of which are curious and valuable, from having belonged to eminent men: of these the most remarkable is a sword of the famous Chevalier Boyard, the knight sans pear et sans reproche. The noble reply of this illustrious dying soldier, made to the Constable of Bourbon, deserves to be remembered. In the war between the Emperor Charles V. and Francis I. of France, the constable had gone over to the emperor, disgusted at the persecutions he met with in France, from the rage of Louisa of Savoy, the queen mother, whose overtures of marriage he had rejected. The emperor made the constable generalissimo of his armies; and in a battle which was fought in the duchy of Milan, and in which the French were obliged to retreat, the Chevalier Boyard was mortally wounded. Charles of Bourbon seeing him in this state, told him how greatly he lamented his fate. “It is not me” said the dying chevalier, “it is not me you should lament, but yourself, who are fighting against your king and country.” A sword of the great Duke of Marlborough, one of Louis XIV. and one of Charles II.: the two last are merely dress swords. A curious silver-basket-hilted broad sword of the Pretender’s, embossed with figures and foliage. But the finest sword in this collection is one of excellent workmanship, which once belonged to the celebrated patriot Hampden; it was executed by Benvenuto Cellini, a celebrated Florentine, who was much employed by Francis I. and Pope Clement VII.

Peter Torrigiano, who executed the monument of Henry VII. in Westminster abbey, endeavoured to bring over Cellini to England, to assist him; but Cellini disliking the violence of his temper, who used to boast that he had given the divine Michael Angelo a blow in the face with his fist, the marks of which he would carry to the grave*, refused to come with him. Vasari, who was contemporary with Cellini, speaks of him in the highest terms. He was originally a goldsmith and jeweller, and executed small figures in alto and basso-relievo with a delicacy of taste and liveliness of imagination not to be excelled: various coins of high estimation were executed by him for the Duke of Florence; and in the latter part of his life, he performed several large works in bronze and in marble with equal reputation. He wrote his own memoirs, which contain much curious and interesting information relative to the contemporary history of the arts.

The ornaments on the hilt and ferrule of the scabbard of this curious sword are in basso-relievo in bronze, and are intended to illustrate the life of David: it is a most beautiful piece of work, and in the highest preservation; it is kept with the greatest care in a case lined with satin.

In the armory is a youthful portrait of Charles XII. of Sweden, and beneath it is a couteau de chasse used by that monarch, of very rude and simple workmanship. A sword of General Moreau’s, and one of Marshal Luckner’s: but it would be impossible in our limits to notice a hundredth part of what is interesting in this collection.

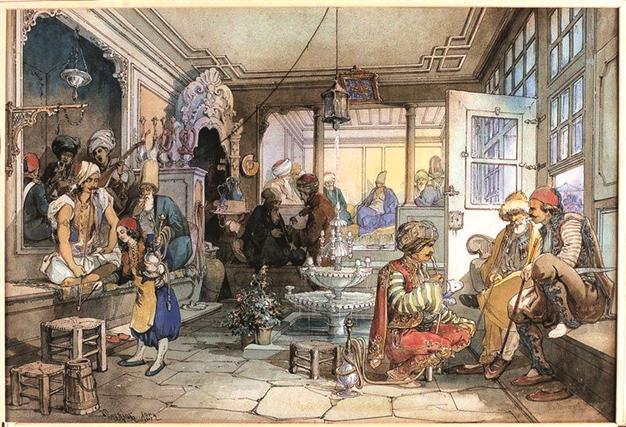

In another room are various specimens of plate armour, helmets, and weapons; some Indian armour of very curious workmanship, composed of steel ringlets, similar to the hauberk worn by the Knights Templars, but not so heavy, and the helmets are of a different construction. Here are also some cuirasses, as worn at present in Germany; a very curious collection of firearms, of various countries, from the match-lock to the modern improvements in the firelock; air-guns, pistols, &c. In this room are also some curious saddles, Mamaluke, Turkish, &c.; some of the Turkish saddles are richly ornamented with pure gold.

Another room contains some Asiatic chain armour, and an effigy of Tippoo Sultaun on horseback, in a dress that he wore. Here are also a model of a cannon and a mortar on new principles; some delicate and curious Chinese works of art in ivory, many rich eastern dresses, and a palanquin of very costly materials.

In another apartment are some curious old English weapons, battle-axes,maces, daggers, arrows, &c.; several specimens also, from the Sandwich and other South Sea Islands, of weapons, stone hatchets, &c.

Our young men of fashion who wish to indulge a taste for antiquarian researches, may project the revival of an old pattern for that appendage of the leg called boots, from the series of them worn in various ages, which form a singular part of this collection.

In presses are kept an immense collection of rich dresses, of all countries; and indeed so extensive and multifarious are the objects, that to be justly appreciated it must be seen. His Royal Highness bestows considerable attention on this museum, and it has in consequence arrived in a few years to a pitch of unrivalled perfection. Among the dresses are sets of uniforms, from a general to a private, of all countries who have adopted uniforms, and military dresses of those who have not. All sorts of banners, colours, horse-tails, &c.; Roman swords, daggers, stilettoes, sabres, the great two-handed swords, and amongst the rest, one with which executions are performed in Germany, on the blade of which is rudely etched, on one side a figure of Justice, and on the other the mode of the execution, which is thus: — the culprit sits upon a chair, and the executioner comes behind him, and at one blow severs the head from the body. There are also some curious portraits in these apartments; besides the one of Charles XII. there is one of Frederic the Great, and various other princes and great men renowned for their talents in the art of war.

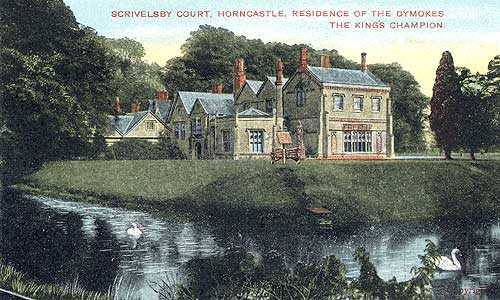

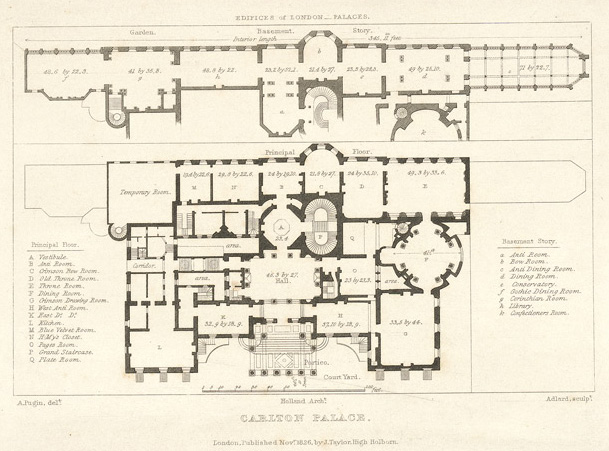

Of the exterior of Carlton House it may be sufficient to observe, that it is situated on the north side of St. James’s Park, and that the principal front faces Pall-Mall*. The portico is a most splendid and magnificent work, of the Corinthian order, enriched with every embellishment that elegant order is capable of receiving. It has been objected, that the other parts of this front are too plain to correspond with so rich a portico: the front is rustic, and therefore does not admit of ornament; but the eye is hurt by the violence of the transition from the most luxuriant decoration to the most rigid plainness. Carlton House, with its court-yard, is separated from Pall-Mall by a dwarf screen, which is surmounted by a very beautiful colonnade. A riding-house and stables, belonging to His Royal Highness, are at the back, immediately contiguous to St. James’s Park. The garden is laid out with the utmost taste and skill of which its limits are capable.

On the 8th of February, 1790, His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales had a state levee, for the first time, at his palace of Carlton House, which was the most numerous of any thing of the kind for many years; and, except the want of female nobility, was more numerous and splendid than the generality of the drawing-rooms even at St. James’s.

Carlton House was a palace belonging to the crown, and presented by His Majesty to His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, on his coming of age, for his public town residence. The old building being out of repair, it was judged proper by Parliament to enable His Majesty to erect the present noble edifice in its room; and Mr. Holland had the honour of being appointed the architect. There is only one thing wanting in this palace, and which, from the present state of the arts, and still more the liberal manner in which they are at present patronized, we hope it is in His Royal Highness’s contemplation to supply. It is a collection of pictures by living artists; these, selected with His Royal Highness’s well known delicacy of taste and judgment, would complete the decorations of this truly magnificent and princely palace.

* This event happened in the palace of Cardinal di Medici: — Torrigiano being jealous of the superior honours paid to Michael Angelo, brutally struck him in the face; his nose was flattened by the blow: the aggressor fled, and entered into the army, but being soon disgusted with that life, left it and came over to England.

* Pall-Mall was formerly laid out as a walk, or place for the exercise of the mall, a game long since disused; its northern side being bounded by a row of trees, and that to the south by the old wall of St. James’s Park.

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000038_00064]](https://susanaellisauthor.blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/the-mysterious-governess-e-reader-copy.jpg)