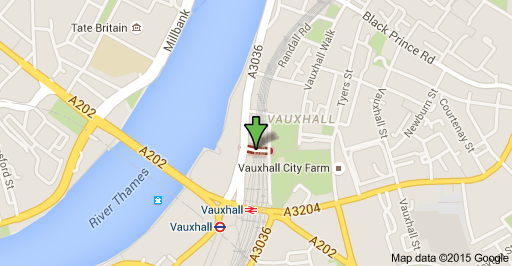

Vauxhall Gardens: A History

David Coke & Alan Borg

The Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens is one of the places I’d love to slip back in time to visit, just to catch a glimpse of what it was like. After recently splurging to buy this lovely coffee-table book, I thought it might make a wonderful subject for a new blog series. But do buy the book too, if you can! The photos are fabulous!

A Splash of the Exotic

The… striking similarity between the Grove and travellers’ descriptions of the great piazza of San Marco in Venice, where citizens were able to arrive by water, take refreshments, listen to music and watch street entertainers, would have highlighted Vauxhall’s exotic pedigree, evoking images of faraway places. This fusion of the familiar with the foreign, a constant feature of the gardens, is likely to have been a deliberate move to give visitors the thrill of romantic and magical scenes without the discomfort of distant travel.

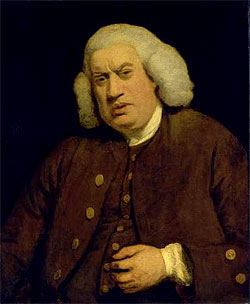

In contrast to the aristocratic or amateur owners of great private gardens, whose wealth allowed them to indulge themselves with indiscriminate allusions to the classical past, ancient mythologies and dreamworlds, Tyers’s overriding consideration in all his investments at Vauxhall was the commercial imperative. Providing that it also furthered his aims, every improvement had to attract more people and increase his profits if it was to justify itself. The sales of food and drink represented the bulk of his income, so the more people he could persuade to purchase refreshments in the gardens, the better it was for his business. Increasing the number of supper-boxes by inserting several sweeping ‘piazzas’, or crescents of supper-boxes, was a very effective and elegant way of achieving this.

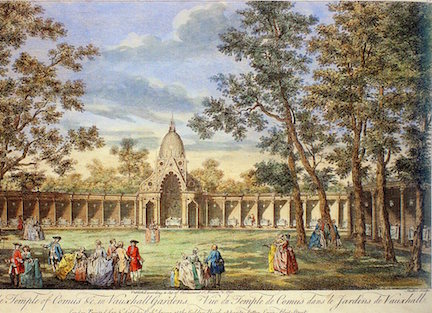

The Temple of Comus (later the Chinese Pavilions)

The Temple of Comus was named… after the god of cheer and good food… Ben Jonson described Comus as the ‘Prime master of arts, and the giver of wit;’ he is also associated with music and with floral decorations. The god thus encompassed all the purposes of the new building, which, although primarily devoted to dining, allowed for the appreciation of the arts and music as well as polite conversation in civilised surroundings.

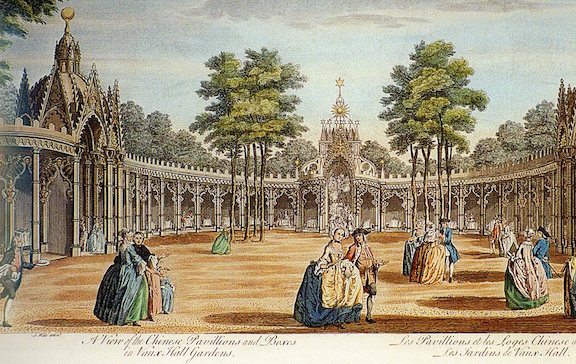

J.S. Muller after Canaletto, A View of the Temple of Comus &c. in Vauxhall Gardens, an engraving hand-colored, 1751 (David Coke’s collection). Families with small children are promenading in the foreground.

Initially, the building was “classical in style, with a colonnade of Ionic columns supporting a straight entablature, topped with urn finials; the semicircle flowed in a smooth curve out of the straight colonnade of the northern range of supper-boxes.” However, the designer also incorporated Gothic arches and “broad-ramped scrolls [that] acted as buttresses for the dome” and other unorthodox details. “The apparent breaking of architectural rules, mingling different styles in the same building, was deliberate and entirely typical of the unorthodox design of the English Rococo, which aimed to create playful, light-hearted works.”

T. Bowles after S. Wale. A View of the Chinese Pavillions and Boxes in Vaux Hall Gardens, engraving. c. 1840 (David Coke’s collection). This is a reprint of Bowles’ plate of 1751, published by Francis West, a Fleet Street optician and printseller who acquired many original plates of London views, probably after the sale of trade stock by Robert Wilkinson, Bowles’ successor, in 1825. The buildings of the Temple of Comus are shown with their newly applied elaborate surface decoration.

The Handel Piazza

J.S. Muller after S. Wale, The Triumphal Arches, Mr. Handel’s Statue &c. in the South Walk of Vauxhall Gardens, engraving, c. 1840 (David Coke’s collection). The early version of the Handel Piazza.

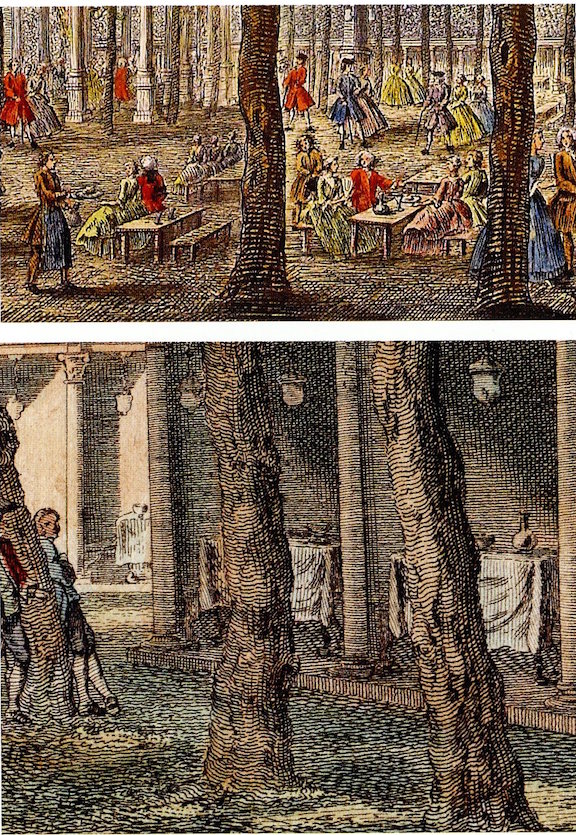

The Handel Piazza on the Grand South Walk started life as a small semicircular colonnade of plain boxes, little more than an open setting for Roubiliac’s statue of the composer… The piazza was built in the simplest Doric order, although the domes of the two terminal pavilions were topped with Gothic lanterns. The rebuilding of 1750-51 created a much broader colonnade, with twenty-two flat-roofed boxes, still of the Doric order, but with urn finials on the roof over each column. As in the Temple of Comus, the central pavilion was more elaborate, marked out by the use of the Ionic order, with swagged decorations between the columns, but here in the Handel Piazza the classical order and restraint were maintained… This new structure added considerably to the number of supper-boxes available on the Grand South Walk… The opposing arrangement and contrasting decorative styles of the Chinese Pavilions and the Handel Piazza epitomise Tyers’s ideological belief in the balance between excess and moderation, with Comus appropriately representing pleasure and excess, and Handel, in his simpler classical architectural setting, representing virtuous sobriety.

J.S. Muller after Canaletto, A View of the Grand South Walk in Vaux Hall Gardens, with the Triumphal Arches, Mr. Handel’s Statue, &c. Engraving, 1751 (British Library, London). On the right is the second version of the Handel Piazza, with more supper-boxes.

The Gothic Piazza

The Gothic Piazza, looking down the Grand South Walk from its western end, is not shown from the front in any engraving of Vauxhall, although Wale’s General Prospect shows it from the back just to the south (right) of the Prince’s Pavilion). It is, however, fully described in Lockman’s Sketch, as

a little Semi-circle of Pavillions, in an elegant Gothic Style […}. At each Foot of this Semi-Circle, stands a lofty Gothic Tent, each having a fine Glass Chandelier, the Lamps in which are of a very peculiar frame, as are those in the grand Tent, built in the Grove, &c. In the Center of this Semi-Circle is a Pavilion, with a Portico before it; and over the Pavillion, a kind of Gothic Tower, with a Turret at Top. Here a Glass Moon was to have been seen; but its Light was found too dazzling for the Eye. Those who survey’d the Alley, the Grove, &c. thro’ this Glass, saw a lovely Representation of them in Miniature. As the painted triumphal Arches before mentioned are in the Grecian Style, and these Pavillions in the Gothic, they form a very pleasing Contrast.

…The implication is that visitors could climb to the top of the central pavilion of this piazza, to look down on the gardens through an optical device or lens during daylight, and after that, after dark, a light was shone through it towards visitors in the Grove, possibly spotlighting courting couples. [Scandal!]

“A remarkable body of original and innovatory architecture”

The group of structures in and around the Grove at the end of the 1740’s, comprising the Orchestra and organ buildings, the supper-boxes and three piazzas, the Prince’s Pavilion, the Turkish Tent and the Rotunda, represent a remarkably body of original and innovatory architecture that was both decorative and practical, achieved by Tyers and his team in the space of just thirteen years. Few other patrons could boast of such a diverse collection of modern works of architecture. The sheer expense incurred in this building spree is evidence of the level of Tyers’s income; as Hogarth’s friend the enameller Jean-André Rouquet wrote at the time, ‘The director of the entertainments of this garden acquires and expends very considerable sums of money there every year. He was born for undertakings of this kind. He is a man of an elegant and bold taste; afraid of no expence, when the point is to divert the public’—or rather, to attract the paying public to Vauxhall.

The fact that this elegant and bold taste was devoted to a pleasure garden, and that the buildings no longer exist, should not detract from their importance in the context of the development of British architecture, and in particular, of British interior design in the eighteenth century. They would have been some of the best-known modern buildings in the country, seen by tens of thousands of visitors every year.

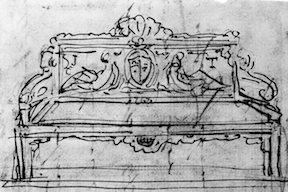

Supper-Box Furniture

In the 1730’s and 1740’s, furniture at Vauxhall… was plain and serviceable, the tables usually covered with baize on linen. Rectangular square-legged farmhouse tables and foxed plain benches served the supper-boxes, with free-standing backless benches and plain tables out in the Grove. The Grove also boasted a number of slatted wooden garden seats, their circular inward-facing form, accessed through a single opening, providing the ideal setting for polite conversation for an intimate rendezvous.

By the early 1750’s, however, contemporary engravings show a number of more elaborate and expensive tables and benches in the supper-boxes. The carved Rococo table-legs, showing below the tablecloths, appear to be ornamented with double-C scrolls.

After this brief period, however, the furniture again reverted to a simple farmhouse style. Indeed, it would be unsurprising if the carved Rococo tables of the 1750’s were found to be too delicate for the abuse they would have received at Vauxhall from the visitors and weather.

Susana’s Vauxhall Blog Post Series

- Vauxhall Gardens: A History

- Vauxhall Gardens: Jonathan Tyers—“The Master Builder of Delight”

- Vauxhall Gardens: A New Direction

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Orchestra and the Supper-Boxes

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Organ, the Turkish Tent, and the Rotunda

- Vauxhall Gardens: Three Piazzas of Supper-Boxes

- Vauxhall Gardens: “whither every body must go or appear a sort of Monster in polite Company”

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Competition

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Artwork, Part I

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Artwork, Part II

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Music, 1732-1859

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Business Side

- Vauxhall Gardens: Developments from 1751-1786

- Vauxhall Gardens: Thomas Rowlandson’s Painting (1785)

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Third Generation of the Tyers Family and the Jubilee of 1786

- Vauxhall Gardens: An Era of Change (1786-1822), Part I

- Vauxhall Gardens: An Era of Change (1786-1822), Part II

- Vauxhall Gardens: An Era of Change (1786-1822), Part III

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Final Years, Part I

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Final Years, Part II

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Final Years, Part III

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Final Years, Part IV

- Vauxhall Gardens: Farewell, for ever

![Shops on the Pulteney Bridge By Erebus555 at English Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://susanaellisauthor.blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/shops_on_pulteney_bridge.jpg?w=714&h=474)

![Sydney Gardens By Plumbum64 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://susanaellisauthor.blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/a_footbridge_over_the_kennet_and_avon_canal_in_sydney_gardens_bath_dated_1800_designed_by_john_rennie_kennet_and_avon_canal.jpg?w=714&h=506)

![Theatre Royal, Bath By MichaelMaggs (Own work) [CC BY-SA 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://susanaellisauthor.blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/theatre_royal_bath.jpg?w=714&h=658)