Amusements of Old London

William B. Boulton, 1901

“… an attempt to survey the amusements of Londoners during a period which began… with the Restoration of King Charles the Second and ended with the accession of Her Majesty Queen Victoria.”

The first mention of a public boxing match in England was a news item in the Protestant Mercury for January 12, 1681:

Yesterday, a match of boxing was performed before his Grace the Duke of Albemarle between the duke’s footman and a butcher. The latter won the prize, as he hath done many before, being accounted, though but a little man, the best at that exercise in England.

That early encounter presents many of the essential features of others which followed it in later times and went to make up the glory of the prize-ring. Here was a noble patron looking on at two men, with no quarrel between them, engaged in punching each other’s heads for the sake of a monetary consideration. Later, as we shall see, the prize-ring claimed all kinds of virtues for its principles and professors. It was “the noble science of self-defence,” “the nurse of the true British spirit,” and many other fine things beside, if we are to believe its votaries and supporters. The prize-ring was in reality a spectacular entertainment which provided amusement for many generations of loafers who found the money to keep it going, and occupation for a relatively small number of courageous men who lived by that strange industry of head-punching.

As mentioned in an earlier post in this series, the prize-fight originated as a duel of swords, primarily, and Mr. Figg’s establishment on Oxford Road (and Southwark Fair) was the place to go to learn “the manly arts of foil play, backsword, cudgelling, and boxing.” George “the Barber” Taylor opened an establishment focused mainly on pugilism, and it was here that the incomparable John Broughton was found, who later organized the profession by providing “a set of rules and regulations which held the field unaltered for a century.”

This paragon among prize-fighters, who really was, as we believe, a good fellow, has been found worthy of a place among the immortals of the great national biography. We learn there that he was born in 1705; began life as a waterman’s apprentice, and found his true vocation quite early in life by thrashing a fellow-waterman. He then went to George Taylor’s booth, beat that hero, and so claimed the championship, and set up an opposition establishment of his own in Hanway Street. Here he had a successful career of unbroken victory, during which he organised pugilism as a profession, and retired, after his only defeat, on a modest fortune to Lambeth. John Broughton died at the age of eighty-four, in 1798, and left some £7000 behind him, and lies buried in Lambeth churchyard under a tombstone with a Latin inscription on it.

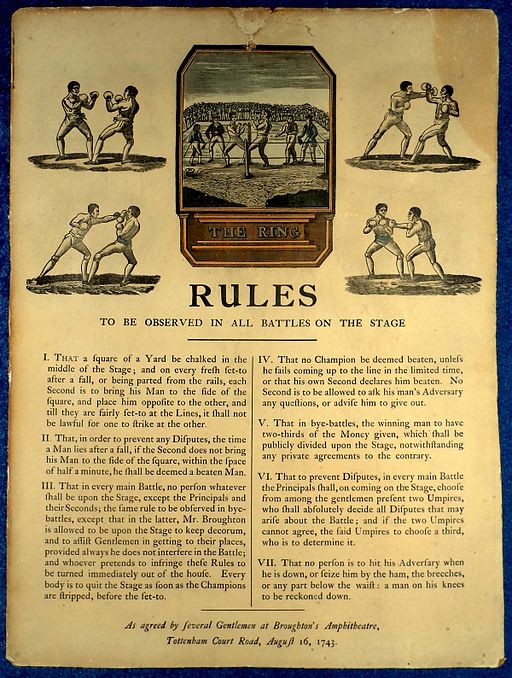

Some of John Broughton’s rules:

They established the all-important principles of the “round” or “set-to,” defined as “a set-to after a fall or being parted at the rails”; the institution of a time limit between the rounds; the appointment of umpires and referee, and the humane regulation “that no person is to hit his adversary when he is down, or seize him by the ham, the breeches, or any part below the waist; a man on his knees to be reckoned down.” They also confirmed the usage of the division of the gate money between victor and vanquished…

John Broughton was also the inventor of boxing-gloves, or “mufflers,” as he called them, which he claimed would “secure them from the inconveniency of black eyes, broken jaws, and bloody noses.”

John Broughton and the Duke of Cumberland

His royal highness, it was said, took him on the Continent; showed him the famous guardsmen of Frederick the Great, and asked him how he would regard a set-to with one of those redoubtable giants. “I should have no objection, your highness, to fight the whole regiment if you would allow me a breakfast between each battle,” was the legendary reply. It is said that the duke’s illustrious brother, Frederick Prince of Wales, gave much encouragement to the clever bruiser…

Those at the top, however, have the furthest to fall, and that’s what happened to Broughton on April 10, 1750, when he rashly agreed to a match between himself and a Norwich butcher named Slack, as a means of settling a dispute. Broughton had not fought for some time and “refused to take training preparation,” and he lost the fight when Slack “dealt that hero a prodigious blow between the eyes,” temporarily blinding him. Not only did Broughton lose the match in under fourteen minutes, but the duke lost ten thousand pounds and “turned his back on his pet of former years.”

Following the duke’s renunciation of Broughton, the authorities closed down his amphitheatre and Broughton retired from the ring. In fact, pugilism itself “fled the country” for a number of years, until it returned to some of the villages near London.

Incidentally, it was the Duke of Cumberland who brought the sport back to London. In 1760, his brother the Duke of York backed a bruiser by the name of Bill Stevens, and Cumberland decided to back Slack, the very same fighter who had beaten his pet Broughton and lost him his ten thousand pounds. While Slack “was acknowledged to have the advantage in the first part of the battle,” Stevens suffered the blows with ease and then “punished the champion’s nob” and ended the winner. Cumberland “retired disgusted from the ring” after this second disappointing loss, and “the ring in London again languished for want of the royal support.”

The Sporting houses

Legal authorities had been trying to shut down these events ever since Cumberland’s withdrawal of patronage of Broughton in 1750, which they managed to do quite successfully in London. In the outskirts, however, where police were not as well-organized or simply not interested, pugilism grew in popularity among all classes, due mainly to the existence of “sporting-houses.”

The sporting houses were public-houses kept by retired prize-fighters, trainers, seconds, or other individuals who had been connected with the prize-ring in their earlier days. A chief part of the usiness of the proprietor of a sporting house was to “give the office,” that is, to furnish to the properly qualified member of the “fancy” the latest intelligence as to the movements of the principals in a forthcoming fight and of the police who were dogging them. Prize-fights were no longer possible near the town, except, as it were, by accident. But the location of a forthcoming battle, the exact hour, the best means of reaching the place of the encounter, the state of the odds on the combatants, and other information of a like interest might always be had at the nearest sporting house by any bona fide member of the fraternity.

As soon as “the office” had been given to the initiated at the sporting houses of Holborn, Soho, Houndsditch or Chelsea, and the date and place of meeting determined beyond any reasonable doubt, the “fancy,” chiefly on horseback, started off on a pilgrimage to the favoured spot. Three days were often spent on the journey when the tactics of the enemy had driven the suffering profession very far afield, to the Sussex or Hampshire downs for instance, Salisbury Plain or the fens of Cambridgeshire.

Organizers apparently set up several alternative sites for their events if one happened to be thwarted by the authorities. In one such situation

…a ring was thrown up on Ashley Common, and between six and seven A.M. “many of the amateurs came dashing direct from London.” Bill Richmond was at the “Magpie” to direct the favoured ones to the proper spot; the multitude soon got “the office” and “followed the bang up leaders” to the common. Mr. Mendoza there rode up to the assembled “fancy” and solemnly assured them that the Marquess and his magistrates would prevent the fight at that spot. The expectant multitude followed that eminent man… to his own inn, “where they found the hero seated in Lord Barrymore’s barouche with the horses turned towards Woburn, and escorted by a hundred and fifty noblemen and gentlemen on horseback and an immense retinue of gigs, tandems, and curricles of every species of vehicle.”

This impressive parade continued for seventeen miles to Sir John Sebright’s park in Hertfordshire, the entire seventeen miles “covered with one solid mass of passengers.”

“Broken-down carriages obstructed the road, knocked-up horses fell and could not be got any further, and many hundreds of gentlemen were happy in being jolted in brick-carts for a shilling a mile.” They most of them reached Sir John Sebright’s demesne by two o’clock, however, where the ring was formed; “the exterior circle was nearly an acre, surrounded by a triple ring of horsemen and a double row of pedestrians, who, notwithstanding the wetness of the ground, lay down with great pleasure, and the forty-foot ring was soon completed.”

Boxing has never appealed to me. A great post thank you.

LikeLike

interesting origination

LikeLike

My like button ain’t working today right now but great post as always xxxx

LikeLike

I am not a big fan of boxing now, but I did watch it with my father on tv when I was younger. I liked reading about Jack Broughton’s story. Interesting to know that he invented boxing gloves or what he called mufflers. I thought it was funny that he thought boxing gloves would protect them from getting black eyes, broken jaws and bloody noses. Yeah right!

LikeLike

Neat post about boxing in Old London.

LikeLike