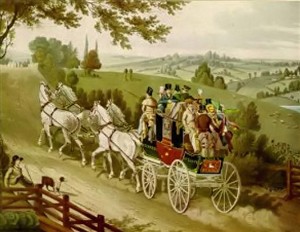

The following post is the fifteenth of a series based on information obtained from a fascinating book Susana recently obtained for research purposes. Coaching Days & Coaching Ways by W. Outram Tristram, first published in 1888, is replete with commentary about travel and roads and social history told in an entertaining manner, along with a great many fabulous illustrations. A great find for anyone seriously interested in English history!

Comment to enter Susana’s October Giveaway, an Anne Boleyn necklace (see right) from Hever Castle in Kent.

Gad’s Hill Place: A Young Boy’s Dream

John Dickens used to point out this stately home as an incentive to his nine-year-old son Charles to work hard. He meant, of course, that his son might someday own such a home, but his son took it literally and used to walk over from Chatham to inspect his future home.

I used to look at it as a wonderful Mansion (which God knows it is not) when I was a very odd little child with the first faint shadows of all my books in my head – I suppose.

Years later, after Charles had achieved fame and fortune, he heard the house was for sale and purchased it, and it became his country retreat in 1857.

Here too from his house on Gad’s Hill (and a very hideous house it is) Charles Dickens…gave novel after wonderful novel to an astonished world, which was never sated with a humour and an observation of life which were indeed Shakespearean; but kept craving and calling for more, and more—till the magician’s brain was hurt, and the magic pen began to move painfully and with labour, and the chair on Gad’s Hill was found one June morning to be empty forever.

I remember the shock of that announcement well. It was as if some pulse in the nation’s heart had stopped beating. There was as it were a feeling that some great embodied joy had left the world, and silence had fallen on places of divine laughter… Yes, the feeling was general, I think, that English literature had suffered an irremediable loss by Dickens’s death; and time has confirmed the fear. We have abandoned laughter in these days for documentary evidence, psychology, realism, and other prescriptions for sleep, and have entered on a literary era which has lost all touch and sympathy with Dickens, and is indeed divinely dull.

Mr. Tristram goes on to quote from the numerous works in which Dickens featured Rochester and its environs: The Pickwick Papers, David Copperfield, Great Expectations and Edwin Drood.

According to Wikipedia, Dickens had in his study “dummy” books with titles such as:

-

Socrates on Wedlock

-

King Henry VIII’s Evidences of Christianity

-

The Wisdom of Our Ancestors: I Ignorance, II Superstition, III The Block, IV The Stake, V The Rack, VI Dirt and VII Disease.

-

A very thin volume entitled The Virtues of Our Ancestors

(I’m loving this man’s sense of humor. Aren’t you? I could think of a few such titles for my own office.)

In 1864 his friend, the actor Charles Fechter, gave him a gift of a Swiss chalet, in 94 pieces. Dickens had it assembled across the street and later had constructed a brick-lined tunnel so that he could go back and forth from his house unobserved. His works from then on were written from the upper floor of the chalet.

Note: The chalet was transferred to the now-defunct Dickens Centre at Eastgate House in Rochester, but you can still see the chalet in the garden.

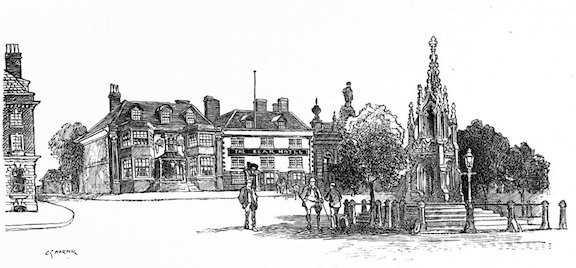

Restoration House in Rochester

There is a passage in Great Expectations referring to this very Restoration House, a place which always took his fancy, and well it might.

“I had stopped,” thus the passage runs, “to look at the house as I passed, and its seared red brick walls, blocked windows, and strong green ivy clasping even the stacks of chimneys with its twigs and tendons, as if with sinewy old arms, made up a rich and attractive mystery.”

This mystery held him to the end. On the occasion of his last visit to Rochester, June 6th, 1870, he was seen leaning on the fence in front of the house, gazing at it, rapt, intent, as if drawing inspiration from its clustering chimneys, its storied walls so rich with memories of the past. It was anticipated, it was hoped, that the next chapter of Edwin Drood would bear the fruits of this reverie. The next chapter was never written.

Index to all the posts in this series

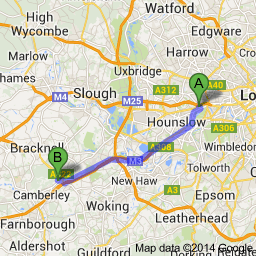

1: The Bath Road: The (True) Legend of the Berkshire Lady

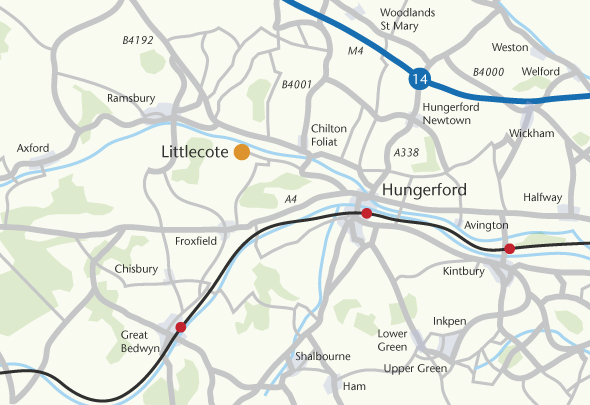

2: The Bath Road: Littlecote and Wild William Darrell

3: The Bath Road: Lacock Abbey

4: The Bath Road: The Bear Inn at Devizes and the “Pictorial Chronicler of the Regency”

5: The Exeter Road: Flying Machines, Muddy Roads and Well-Mannered Highwaymen

6: The Exeter Road: A Foolish Coachman, a Dreadful Snowstorm and a Romance

7: The Exeter Road in 1823: A Myriad of Changes in Fifty Years

8: The Exeter Road: Basingstoke, Andover and Salisbury and the Events They Witnessed

9: The Exeter Road: The Weyhill Fair, Amesbury Abbey and the Extraordinary Duchess of Queensberry

10: The Exeter Road: Stonehenge, Dorchester and the Sad Story of the Monmouth Uprising

11: The Portsmouth Road: Royal Road or Road of Assassination?

12: The Brighton Road: “The Most Nearly Perfect, and Certainly the Most Fashionable of All”

13: The Dover Road: “Rich crowds of historical figures”

14: The Dover Road: Blackheath and Dartford

15: The Dover Road: Rochester and Charles Dickens

16: The Dover Road: William Clements, Gentleman Coachman

17: The York Road: Hadley Green, Barnet

18: The York Road: Enfield Chase and the Gunpowder Treason Plot

19: The York Road: The Stamford Regent Faces the Peril of a Flood

20: The York Road: The Inns at Stilton

21: The Holyhead Road: The Gunpowder Treason Plot

22: The Holyhead Road: Three Notable Coaching Accidents

23: The Holyhead Road: Old Lal the Legless Man and His Extraordinary Flying Machine

26: Flying Machines and Waggons and What It Was Like To Travel in Them