Vauxhall Gardens: A History

David Coke & Alan Borg

The Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens is one of the places I’d love to slip back in time to visit, just to catch a glimpse of what it was like. After recently splurging to buy this lovely coffee-table book, I thought it might make a wonderful subject for a new blog series. But do buy the book too, if you can! The photos are fabulous!

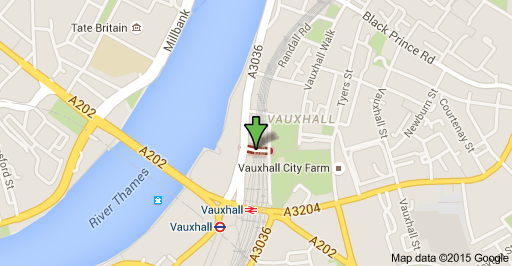

The year 1751 marked the pinnacle of Jonathan Tyers’s success. After twenty years his vision was at last complete, and the basic ensemble of landscape and buildings was in place. The following year the act to license places of public entertainment was passed, leaving just the three major gardens, Marylebone, Ranelagh and Vauxhall, with a virtual monopoly for the time being. Vauxhall’s prestige would never be higher, and the artworks, design and refreshments would never be surpassed. The opening night of the season, Monday 20 May, was attended by about seven thousand visitors, all eager to see the most recent changes, and to enjoy the new musical performances.

A contemporary publication that effectively and entirely objectively sums up Tyers’s achievements is Stephen Whatley’s guide to the main towns and villages of interest in the country, England’s Gazetteer. Apart from a short description of classical statuary at Cuper’s Gardens, the only entry for a pleasure garden is under “Foxhall (Surry)’ (neither Ranelagh nor Marylebone merited a mention):

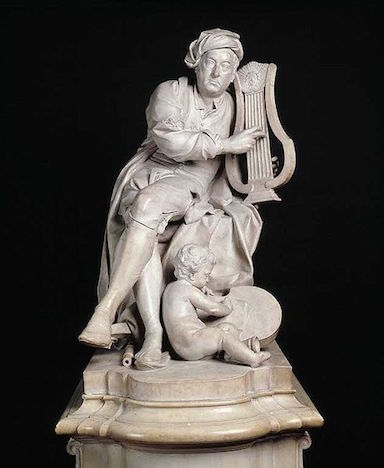

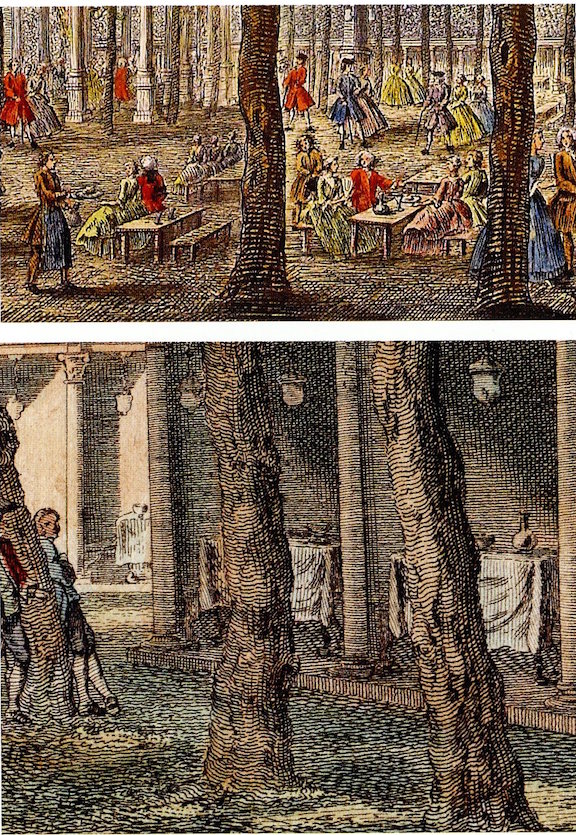

This is the place, where are those called Spring Gardens, laid out in so grand a taste, that they are frequented, in the 3 summer months, by most of the nobility and gentry, then in and near London; and are often honoured with some of the royal family, who are here entertained with the sweet song of numbers of nightingales, in concert with the best band of musick in England. Here are fine pavilions, shady groves, and most delightful walks, illuminated by above 1000 lamps, so disposed, that they all take fire together, almost as quick as lightning, and dart such a sudden blaze, as is perfectly surprizing. Here are, among others, 2 curious statues of Apollo the god, and Mr. Handel the master of musick; and in the centre of the area, where the walks terminate, is erected the temple for the musicians, which is encompassed all round with handsome seats, decorated with pleasant paintings, on subjects most happily adapted to the season, place, and company.

The growing success of Vauxhall can be attributed directly to Jonathan Tyers’s continual upgrades in music, lights, and fine costumes. Profits from major events were plowed right back into the gardens, which is what drew an increasing number of visitors.

The Pillared Saloon

Prior to the 1751 season, the Pillared Saloon was opened up and an extension created that provided for space for artwork and made space for half again as many visitors. Unfortunately, the design was awkward and unsophisticated and was probably created by inexperienced students at the St. Martin’s Lane Academy.

H. Roberts after S. Wale, The Inside of the Elegant Music Room in Vaux Hall Gardens, engraving, 1752 (British Library, London)

The new indoor orchestra stand opposite the Pillared Saloon, behind a balustrade that separated it from the audience, shared its awkward style; the same foliate columns framed it, and similar paintings decorated its ceiling. It must have been a substantial space, as an Irish visitor in 1752 claimed that he saw fifty-four musicians performing there, accompanying the singers Thomas Lowe and Isabella Burchell.

The Triumphal Arches and Decorative Paintings

In contrast to the gaucherie of the Pillared Saloon, the three triumphal arches built over the South Walk at about the same time presented a more elegant, though more predictable, classical appearance… [T]hey were designed by ‘an ingenious Italian’ and made of timber and painted canvas.

J.S. Muller after S. Wale, The Walk of Triumphal Arches and the Statue of Mr. Handle in Vauxhall Garden, engraving, 1751 (British Library, London).

…the undeniably theatrical view through the three Vauxhall arches to the piece of scenery at the end of the walk must have been impressive; the vista was focused and enclosed by the surrounding trees, and the trompe-l’oeil effect of the scenery seen at the proper distance was intended to draw visitors to that end of the walk, where, on arrival, they could marvel at the skill of the artist, who had fooled them into thinking it was a three-dimensional object.

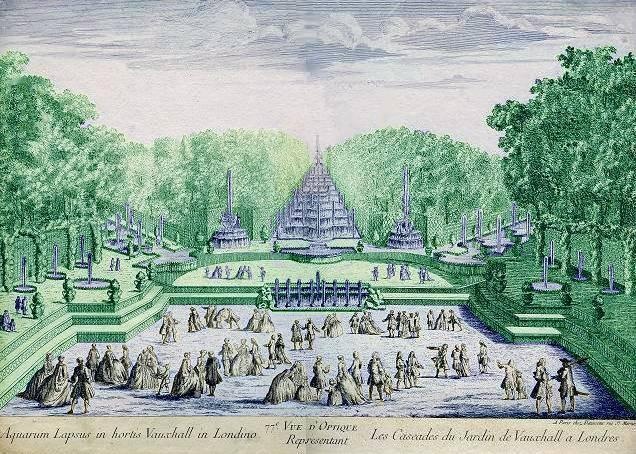

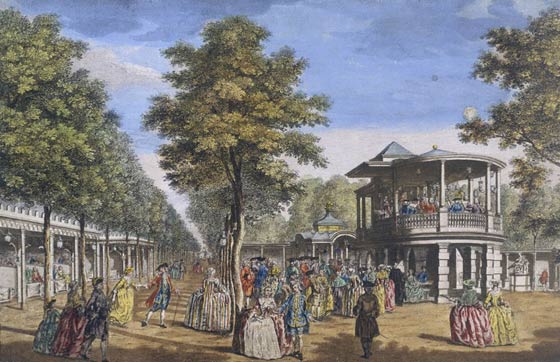

E. Rooker after Canaletto, A Vew of the Center Cross Walk &c. in Vauxhall Gardens, engraving, 1751 (British Library, London).

In addition to these theatrical-esque arches, four large scenes were painted and installed at the end of the walks, to camouflage the surrounding landscape and introduce a bit of fantasy. The Temple of Neptune, at the end of the South Walk, was soon replaced by the ruins of Palmyra, after the publication of Robert Wood’s journey there. A painting of an alcove of three niches with figures of Flora and the Genii, at the end of the Dark Walk, was replaced with a scene of a Chinese Garden in 1762. “At the opposite end was an altogether more eccentric scene of another alcove, but this one bore a representation of a scaffolding and ladder ready for artists to work on the canvas.” The explanation for this:

An eminent artist, but of dissipated character, was employed by the first proprietors of the gardens to paint some classical designs at the end of one of the walks; but the delay in their completion so irritated the proprietor, that, having to leave London for a fortnight, he declared to the artist that he would listen to no further excuses, and that if he found his scaffold, paint-pots, &c. on his return, they should be thrown over the garden wall. On his return, perceiving, as he thought, in the same position, the scaffold, paint-pots, &c., he hastened to the spot to put his threat into execution, when, to his great amazement, he found them to be so accurately pictured on the canvas, that he ever after lavished the most extravagant praises upon the delinquent artist.

The Cascade

The most popular of Tyers’s additions in the 1750’s was the artificial Cascade, which was likely conceived by Frances Hayman, from his work with scenery and special effects in the theater.

The Cascade was concealed behind a curtain which was drawn back at a particular time in the evening, as night fell, to reveal a three-dimensional illuminated scene of a landscape with a precipitous waterfall: the illusion was created with sheets of tin fixed to moving belts, turned by a team of Tyers’s lamplighters; when it was running, the noise and spectacle must have been terrific.

Throughout its existence the Cascade underwent various improvements, enlargements, alterations, replacements, demolitions, and moves, which continued into the 1840’s. No visual representation of it survives, but at the height of its popularity in 1762 an anonymous author described it as:

a most beautiful landscape in perspective of a fine open hilly country with a miller’s house and a water mill, all illuminated by concealed lights; but the principal object that strikes the eye is a cascade or water fall. The exact appearance of water is seen flowing down a declivity; and the turning the wheel of the mill, it rises up in a foam at the bottom, and then glides away. This moving picture attended with the noise of the cascade has a very pleasing and surprising effect on both the eye and ear.

Until well into the 1820’s, when it was demolished to make way for the new Ballet Theatre, the Cascade continued to delight and surprise Vauxhall audiences, with depictions of the tidal race and watermill at London Bridge, of distance military encampments, and other scenes.

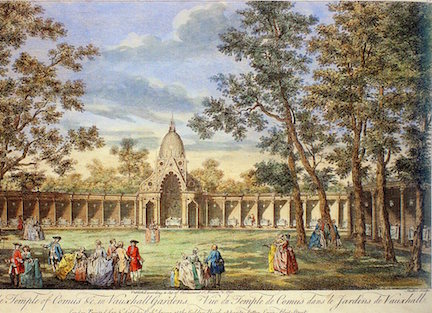

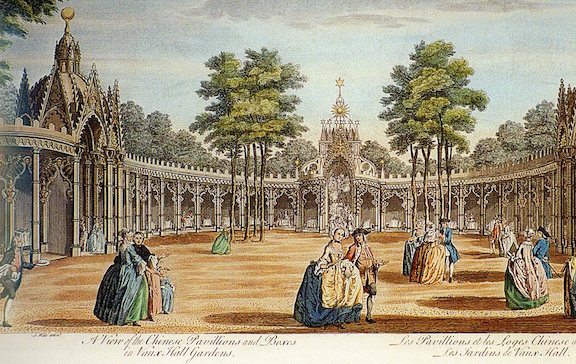

The Gothic Orchestra

The original Orchestra building had outlived its usefulness, and was replaced in 1757-8 with a sort of Gothic-style building, made of wood and plaster and painted white and ‘bloom’, whatever that is. This building remained through the end of the gardens, having a domed roof with a “finial of Prince of Wales feathers”. The organ and musicians occupied the top floor, with supper-boxes on the bottom. The upper floor had graduated seating that made the musicians visible to the audience.

Anon., A Perspective View of the Grand Walk in Vauxhall Gardens, and the Orchestra, engraving (David Coke’s collection), from the Gentleman’s Magazine (August 1765). The earliest view of the new Gothic Orchestra, built in 1757.

The Company

As we have mentioned previously, Vauxhall attracted a diverse group of visitors, more than any other entertainment of the period. The bulk of its income, however, came from the “Smarts,” which were middle-class young men, known for their licentiousness and self-indulgence, who came to show off to their female companions. A press reporter put it this way in July 1738:

The Smarts are, as it were, the sole Authors of our publick diversions at the Theatre they have a majority of the pit and the boxes: to them the Opera owes its subsistence, and Vaux Hall, the agreeable Vauxhall! would be a wilderness without them.

A big draw for the lower classes was the opportunity to encounter the upper classes, royalty, or other celebrities, that they would not normally be allowed anywhere near.

An account of a visit by an upper-class party is given by Horace Walpole:

I had a card from Lady Caroline Petersham to go with her to Vauxhall. I went accordingly to her house at half an hour after seven, and found her and little Ashe, or the pollard Ashe, as they call her; they had just finished their last layer of red, and looked as handsome as crimson could make them. […] We got into the best order we could and marched to our barge, with a boat of French horns attending and little Ashe singing. We paraded some time up the river and at last debarked at Vauxhall […]. At last we assembled in our booth, Lady Caroline in the front, with the vizor of her hat erect, and looking gloriously jolly and handsome. She had fetched my brother Orford from the next box, where he was enjoying himself with his Norsa and his petite partie, to help us to mince chickens. We minced seven chickens into a china dish, which Lady C. stewed over a lamp with three pats of butter and a flagon of water, stirring and rattling and laughing, and we every minute expecting to have the dish fly about our ears. She had brought Betty [Neale] the fruit girl, with hampers of strawberries and cherries from Rogers’s, and made her wait upon us, and then made her sup by us at a little table […]. In short, the whole air of our party was sufficient as you will easily imagine to take up the whole attention of the garden, so much so, that from eleven o’clock till half an hour after one, we had the whole concourse round our booth, at last they came into the little gardens of each booth on the sides of ours, till Harry Vane took up a bumper and drank their healths, and was proceeding to treat them with still greater freedom. It was three o’clock before we got home.

Then there was Henry Timberlake, who brought a group of Cherokee Indians to the gardens on two occasions, the second advertised ahead of time drawing ten thousand curious onlookers. (Note: those Cherokees had a very busy schedule. Take a peek here.)

A ‘silent majority’ of visitors came from the professional classes, lawyers, doctors, parsons, and increasingly in the 1780’s, after Tyers’s death, prostitutes and the demi-monde.

Anon., The Vauxhall Demi-Rep, engraving, 1772 (Senate House Library, London). One of the working girls who frequented the gardens. Less a prostitute than an escort, the demo-rep would join an all-male party to titillate and amuse the men.

Susana’s Vauxhall Blog Post Series

- Vauxhall Gardens: A History

- Vauxhall Gardens: Jonathan Tyers—“The Master Builder of Delight”

- Vauxhall Gardens: A New Direction

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Orchestra and the Supper-Boxes

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Organ, the Turkish Tent, and the Rotunda

- Vauxhall Gardens: Three Piazzas of Supper-Boxes

- Vauxhall Gardens: “whither every body must go or appear a sort of Monster in polite Company”

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Competition

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Artwork, Part I

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Artwork, Part II

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Music, 1732-1859

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Business Side

- Vauxhall Gardens: Developments from 1751-1786

- Vauxhall Gardens: Thomas Rowlandson’s Painting (1785)

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Third Generation of the Tyers Family and the Jubilee of 1786

- Vauxhall Gardens: An Era of Change (1786-1822), Part I

- Vauxhall Gardens: An Era of Change (1786-1822), Part II

- Vauxhall Gardens: An Era of Change (1786-1822), Part III

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Final Years, Part I

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Final Years, Part II

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Final Years, Part III

- Vauxhall Gardens: The Final Years, Part IV

- Vauxhall Gardens: Farewell, for ever