The following post is the seventeenth of a series based on information obtained from a fascinating book Susana recently obtained for research purposes. Coaching Days & Coaching Ways by W. Outram Tristram, first published in 1888, is replete with commentary about travel and roads and social history told in an entertaining manner, along with a great many fabulous illustrations. A great find for anyone seriously interested in English history!

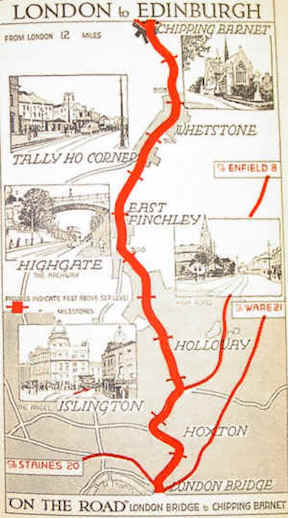

The Great North Road

And Barnet is soon a memory on the great north road. A memory however which shows some claim to “recollection dear”, fixing as it does the site of a great battle and of a highwayman’s exploits, which have occupied almost the same space in history—I mean fiction—No! I mean history. To come to details:—On Hadley Green, half-a-mile to the north of the town, was fought on a raw, cold and dismal Easter Day, in the year 1471, the famous battle between the Houses of York and Lancaster which ended in the death of the king-maker, and established Edward IV on the throne; and behind an oak tree, which still stands opposite the Green Man at the junction of the York and Holyhead Roads, the immortal Dick Turpin used to sit silent on his mare, Black Bess, patiently waiting for some traveller to speak to.

And Barnet is soon a memory on the great north road. A memory however which shows some claim to “recollection dear”, fixing as it does the site of a great battle and of a highwayman’s exploits, which have occupied almost the same space in history—I mean fiction—No! I mean history. To come to details:—On Hadley Green, half-a-mile to the north of the town, was fought on a raw, cold and dismal Easter Day, in the year 1471, the famous battle between the Houses of York and Lancaster which ended in the death of the king-maker, and established Edward IV on the throne; and behind an oak tree, which still stands opposite the Green Man at the junction of the York and Holyhead Roads, the immortal Dick Turpin used to sit silent on his mare, Black Bess, patiently waiting for some traveller to speak to.

A Not-So-Gallant Highwayman

Let me preface this by saying that the real Dick Turpin was a violent criminal and not the sort of gallant Robin Hood frequently found in historical romances and in William Harrison Ainsworth’s Rookwood. His gangs robbed, maimed, killed and raped. It was due to men like him that coaches traveling on the highways of England often had armed outriders for protection. Nor was he a particularly handsome fellow. The London Gazette describes him as:

Let me preface this by saying that the real Dick Turpin was a violent criminal and not the sort of gallant Robin Hood frequently found in historical romances and in William Harrison Ainsworth’s Rookwood. His gangs robbed, maimed, killed and raped. It was due to men like him that coaches traveling on the highways of England often had armed outriders for protection. Nor was he a particularly handsome fellow. The London Gazette describes him as:

Richard Turpin, a butcher by trade, is a tall fresh coloured man, very much marked with the small pox, about 26 years of age, about five feet nine inches high, lived some time ago in Whitechapel and did lately lodge somewhere about Millbank, Westminster, wears a blue grey coat and a natural wig.

—The London Gazette: no. 7379. p. 1. 22 February 1734. )

Prior to taking up coach-robbing, Turpin was part of a gang who did what we would call home invasions—beating and torturing the occupants, in one case forcing a bare-buttocked man to sit on the fire. Scenes right out of Criminal Minds! A behavioral analyst would understand this better than I, because I simply cannot imagine why anyone would do this for the piddly amount they came away with—often less than thirty pounds!

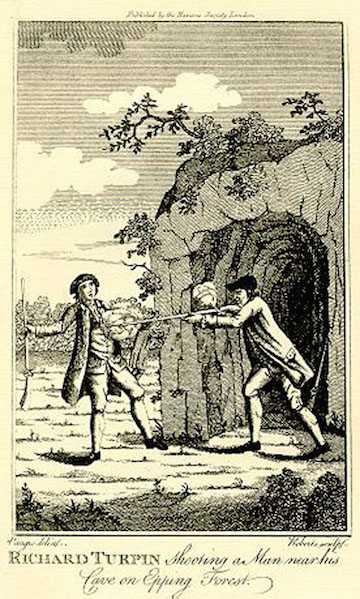

That gang—termed the “Essex Gang”—ceased to exist when authorities rounded up and executed many of the members in 1735. That’s when our Dick turned to robbing coaches. He was hiding out in Epping forest when he shot and killed a servant who recognized him.

It having been represented to the King, that Richard Turpin did on Wednesday the 4th of May last, barbarously murder Thomas Morris, Servant to Henry Tomson, one of the Keepers of Epping-Forest, and commit other notorious Felonies and Robberies near London, his Majesty is pleased to promise his most gracious Pardon to any of his Accomplices, and a Reward of 200l. to any Person or Persons that shall discover him, so as he may be apprehended and convicted. Turpin was born at Thacksted in Essex, is about Thirty, by Trade a Butcher, about 5 Feet 9 Inches high, brown Complexion, very much mark’d with the Small Pox, his Cheek-bones broad, his Face thinner towards the Bottom, his Visage short, pretty upright, and broad about the Shoulders.

—The Gentleman’s Magazine (June 1737)

Escaping to the north, he began calling himself Palmer, and under that name, was accused of shooting another man’s cock (a chicken, I believe!) and tossed in the House of Correction at Beverley. Suspected of horse theft, he was transferred to York Castle and sentenced to death for that. It wasn’t until he wrote a letter to his brother-in-law—who promptly refused it—that his true identity was discovered. He was executed at Knavesmire and buried at St. George’s Church in Fishergate. Ironically, his body was robbed by bodysnatchers, who made their living selling bodies to medical schools—but it was recovered soon after and reburied.

Index to all the posts in this series

1: The Bath Road: The (True) Legend of the Berkshire Lady

2: The Bath Road: Littlecote and Wild William Darrell

3: The Bath Road: Lacock Abbey

4: The Bath Road: The Bear Inn at Devizes and the “Pictorial Chronicler of the Regency”

5: The Exeter Road: Flying Machines, Muddy Roads and Well-Mannered Highwaymen

6: The Exeter Road: A Foolish Coachman, a Dreadful Snowstorm and a Romance

7: The Exeter Road in 1823: A Myriad of Changes in Fifty Years

8: The Exeter Road: Basingstoke, Andover and Salisbury and the Events They Witnessed

9: The Exeter Road: The Weyhill Fair, Amesbury Abbey and the Extraordinary Duchess of Queensberry

10: The Exeter Road: Stonehenge, Dorchester and the Sad Story of the Monmouth Uprising

11: The Portsmouth Road: Royal Road or Road of Assassination?

12: The Brighton Road: “The Most Nearly Perfect, and Certainly the Most Fashionable of All”

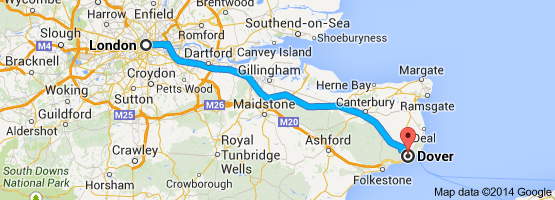

13: The Dover Road: “Rich crowds of historical figures”

14: The Dover Road: Blackheath and Dartford

15: The Dover Road: Rochester and Charles Dickens

16: The Dover Road: William Clements, Gentleman Coachman

17: The York Road: Hadley Green, Barnet

18: The York Road: Enfield Chase and the Gunpowder Treason Plot

19: The York Road: The Stamford Regent Faces the Peril of a Flood

20: The York Road: The Inns at Stilton

21: The Holyhead Road: The Gunpowder Treason Plot

22: The Holyhead Road: Three Notable Coaching Accidents

23: The Holyhead Road: Old Lal the Legless Man and His Extraordinary Flying Machine

26: Flying Machines and Waggons and What It Was Like To Travel in Them