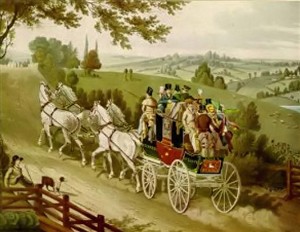

The following post is the eighth of a series based on information obtained from a fascinating book Susana recently obtained for research purposes. Coaching Days & Coaching Ways by W. Outram Tristram, first published in 1888, is chock full of commentary about travel and roads and social history told in an entertaining manner, along with a great many fabulous illustrations. A great find for anyone seriously interested in English history!

Basingstoke

In 1645 Cromwell took Basing House after a four-year struggle, stripped the lead off the roof of the Abbey in order to cast bullets, leaving the house in ruins. Basingstoke, however was a popular place for coaches to stop for meals.

Between Basingstoke and Andover is a “desolate country” where coaches could make good time. The White Hart in Whitchurch was a “bustling place” where coaches from London to Salisbury and Oxford to Winchester crossed each other.” (Note: it’s still there and has fifteen rooms available should you desire to stay there!)

Andover

Here Henry VII rested from his labours after suppressing the insurrection of Perkin Warbeck; but whether the miserly Tudor put up at the Star and Garter, or the everlasting White Hart, or their medieval equivalents, if there were any, is more than I can say. It was upon Andover to link another royalty with the place, that James II fell back, after the breaking-up of the camp at Salisbury. Here it was that he was deserted by Prince George [Prince of Denmark, his daughter Anne’s husband], remarkable for his impenetrable stupidity and his universal panacea for all contingencies in a catch-word. Whatever happened, “Est-il possible?” was his exclaim. He supped with the king, who was at the moment overwhelmed naturally enough with his misfortunes, said nothing during a dull meal, but directly it was over slipped out to the stable in the company of the Duke of Ormond, mounted, and rode off. James did not exhibit much surprise on learning the adventure, being used to desertion by this time. He merely remarked, “What, is ‘Est-il possible?’ gone too! A good trooper would have been a greater loss;” and left for London—I was going to say by the next coach.

Two important coaching roads diverge about a half-mile out of Andover, which was also the scene of an escaped lioness on the Exeter Mail on October 20, 1816.

Salisbury

“One of the most picturesque towns in the south of England,” Salisbury, where the Quicksilver (which could do 175 miles in 18 hours, our author notes repeatedly) stopped to change horses, “is almost exactly half way between Exeter and London.”

“One of the most picturesque towns in the south of England,” Salisbury, where the Quicksilver (which could do 175 miles in 18 hours, our author notes repeatedly) stopped to change horses, “is almost exactly half way between Exeter and London.”

The town of Salisbury, which is eighty miles seven furlongs from Hyde Park Corner, is chiefly remarkable for its cathedral; and it owes this agreeable notoriety to the north wind. This may sounds trange in the ears of those who have not, attired as shepherds, highwaymen or huntsmen, braved the elements in the surrounding plain. Those however who have enjoyed this fortune, will not be surprised to learn, that when the winds raged in the good old days of 1220 round the original church of Old Sarum, which was quite unprotected and perched upon a hill, the congregation were utterly unable to hear the priests say mass; and no doubt they were unable to hear the sermon too. This fact much exercised the good Bishop Poore; and so, a less windy site having opportunely been revealed to him in a dream by the Virgin he got a license from Pope Honorius for removal. Which done—with a medieval disregard for the safety of the local cowherd or government inspector—he aimlessly shot an arrow into the air from the ramparts of Old Sarum, and (unlike Mr. Longfellow’s hero), having marked where it fell, there laid the foundations of the existing beautiful church.

The first among the myriad of royal visitors to Salisbury was Richard II, “who was here immediately before his expedition to Ireland, where he should clearly never have gone.” Apparently the town was not at all impressed with his “amiable inclination towards charging his subjects with his outings,” considering the fact that his household consisted of “ten thousand persons, three hundred of whom were cooks” and for him they had to provide tables. The town “a short time after expressed their thanks for his visit, by, with almost indecent alacrity, espousing the cause of Henry.”

In 1484

Richard III

…the hunchbacked Richard honoured Salisbury with his presence; but he was not I expect in the best of tempers, for here to him was brought the Buckingham we have all read of in the play, who had just seized the fleeting opportunity to head an insurrection against the king, in an unprecedentedly wet season in Wales. The result was that he was unable to cross the Severn, and this misfortune brought him too to Salisbury, where Richard was waiting to superintend his execution at what is now the Saracen’s Head.

In the courtyard of this inn, which was then called the Blue Boar, and not “in an open space,” as Shakespeare has described it (as if he were speaking of Salisbury Plain), Buckingham had his head cut oft according to contemporary prescription. We have none of us seen the episode presented on the stage, but we have read the carpenters’ scene, which Shakespeare wrote in, to give the gentleman who originally played Buckingham a chance, and allow a few moments more preparation for Bosworth Field. And we may recollect that it consists princiapply in Buckingham asking whether King Richard will not let him speak to him, and on being told not at all, informing the general company, at some length, that it is All-Souls’ Day, and that as soon as he has been beheaded, he intends to commence “walking”.

Although the inn has been replaced by Debenham’s, a department store, some say they have seen or experienced the Duke’s ghost, so ladies, you might want to reconsider using the dressing rooms there—just an FYI.

After Richard and Buckingham, there came to Salisbury in the way of kings, Henry VII in 1491. Henry VIII in 1535 with Ann Boleyn, already in all probability engaged in those sprightly matrimonial differences as to men and the things which culminated the year following on Tower Green. Next in order, came to Salisbury, Elizabeth, bound for Bristol, bent, as on all her royal progresses, on keeping her nobility’s incomes within bounds, and shooting tame stags that were induced to meander before her bedroom windows. After the virgin queen came James I, who liked the solitudes which surrounded the Salisbury of those days, for the two-fold reason, firstly, because they saved him in a large measure from the invasion of importunate suitors (who were afraid of having their purses taken on Salisbury Plain before they could proffer their supplications), and, secondly, because they were well stocked with all sorts of game on which he could wreak his royal and insatiable appetite for hunting. The “open” nature of the country might perhaps be added as another reason for the sporting king’s liking for the place: for James was no horseman, and as he was in no danger of meeting a hedge in an area of thirty miles, the going must have suited him down to the ground.

Sir Walter Raleigh

It was also hear that Sir Walter Raleigh, upon his return to England from an unsuccessful expedition to Spain, tried to gain audience with James to explain himself and beg pardon, but was forced to return to London where he was imprisoned and executed.

The merry monarch [Charles II] was here twice, but on neither occasion, I suspect was he peculiarly merry; for after the battle of Worcester, when he lay concealed near the town for a few days, and his companions used to meet at the King’s Arms in John Street, to plan his flight, the Ironsides were much too close on his track to allow opportunity for jesting; and when he came here as king in 1665, all but the most forced mirth was banished from a court which dreaded every day to be stricken by the plague.

Index to all the posts in this series

1: The Bath Road: The (True) Legend of the Berkshire Lady

2: The Bath Road: Littlecote and Wild William Darrell

3: The Bath Road: Lacock Abbey

4: The Bath Road: The Bear Inn at Devizes and the “Pictorial Chronicler of the Regency”

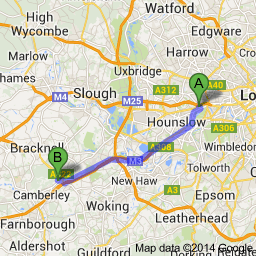

5: The Exeter Road: Flying Machines, Muddy Roads and Well-Mannered Highwaymen

6: The Exeter Road: A Foolish Coachman, a Dreadful Snowstorm and a Romance

7: The Exeter Road in 1823: A Myriad of Changes in Fifty Years

8: The Exeter Road: Basingstoke, Andover and Salisbury and the Events They Witnessed

9: The Exeter Road: The Weyhill Fair, Amesbury Abbey and the Extraordinary Duchess of Queensberry

10: The Exeter Road: Stonehenge, Dorchester and the Sad Story of the Monmouth Uprising

11: The Portsmouth Road: Royal Road or Road of Assassination?

12: The Brighton Road: “The Most Nearly Perfect, and Certainly the Most Fashionable of All”

13: The Dover Road: “Rich crowds of historical figures”

14: The Dover Road: Blackheath and Dartford

15: The Dover Road: Rochester and Charles Dickens

16: The Dover Road: William Clements, Gentleman Coachman

17: The York Road: Hadley Green, Barnet

18: The York Road: Enfield Chase and the Gunpowder Treason Plot

19: The York Road: The Stamford Regent Faces the Peril of a Flood

20: The York Road: The Inns at Stilton

21: The Holyhead Road: The Gunpowder Treason Plot

22: The Holyhead Road: Three Notable Coaching Accidents

23: The Holyhead Road: Old Lal the Legless Man and His Extraordinary Flying Machine

24: The Holyhead Road: The Coachmen “More Celebrated Even Than the Most Celebrated of Their Rivals” (Part I)

25: The Holyhead Road: The Coachmen “More Celebrated Even Than the Most Celebrated of Their Rivals” (Part II)

26: Flying Machines and Waggons and What It Was Like To Travel in Them

27: “A few words on Coaching Inns” and Conclusion

She fixed those wonderful eyes on him, more lethal than a backwoods rifleman. “Shall I lead the way, Captain?”

She fixed those wonderful eyes on him, more lethal than a backwoods rifleman. “Shall I lead the way, Captain?” Married to my high school sweetheart, I live on a farm in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia surrounded by my children, grandbabies, and assorted animals. An avid gardener, my love of herbs and heirloom plants figures into my work. The rich history of Virginia, the Native Americans and the people who journeyed here from far beyond her borders are at the heart of my inspiration. In addition to American settings, I also write historical and time travel romances set in the British Isles, and nonfiction about gardening, herbal lore, and country life.

Married to my high school sweetheart, I live on a farm in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia surrounded by my children, grandbabies, and assorted animals. An avid gardener, my love of herbs and heirloom plants figures into my work. The rich history of Virginia, the Native Americans and the people who journeyed here from far beyond her borders are at the heart of my inspiration. In addition to American settings, I also write historical and time travel romances set in the British Isles, and nonfiction about gardening, herbal lore, and country life.