The following post is the eleventh of a series based on information obtained from a fascinating book Susana recently obtained for research purposes. Coaching Days & Coaching Ways by W. Outram Tristram, first published in 1888, is chock full of commentary about travel and roads and social history told in an entertaining manner, along with a great many fabulous illustrations. A great find for anyone seriously interested in English history!

The Portsmouth Road has been described to me by one having authority as the Royal Road: and certainly kings and queens have passed up and down it, eaten and drunken in the Royal Rooms, still to be seen in some of the old inns; snored in the Royal Beds (also in places to be seen, but not slept in), and dreamed of ruts of bogs, and blasted heaths and impassable morasses, and all the sundry and other mild discomforts which our ancestors, whether kings or cobblers, had to put up with; or those among them at all events who travelled when the weather was rainy, and there were no real roads to travel upon.

To me however the Portsmouth Road—so called Royal—presents itself in a less august guise; so much so that if I were asked to give it a name whereby it might be especially distinguished, I should be inclined, I think, to call it the Road of Assassination. And it will be found to have claim to the title.

The Unknown Sailor

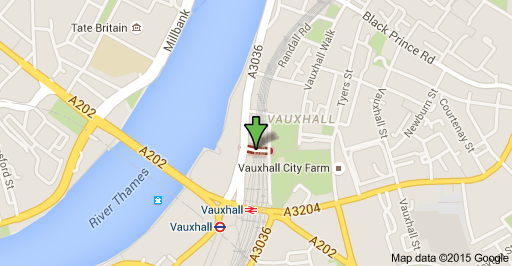

The Portsmouth Road after Godalming and Milford consisted of a “gravelly road” for five miles up Hindhead Hill that led them directly to a “silent memorial of murder,” a gravestone reminder

of a barbarous murder committed on the spot on the person of an unknown sailor (who lies buried in Thursley Churchyard, a few miles off); and airs also with some satisfaction the feeling then very prevalent (before Scotland Yard was), that murderers are a class who invariably fall into the hands of justice. We are perhaps not so credulous as this nowadays; but we put our trust in a large detective force when our throats have been cut, and hope for the best. The local police of 1786 however could have given many of our shining lights a lesson, it seems to me; for on the very afternoon of September the 4th in that year (which was the date of the murder) they apprehended three men named Lonegon, Casey, and Marshall, twelve miles further down the road…engaged in the unwise exercise of selling the murdered man’s clothes. For this, and previous indiscretions, they were presently hanged in chains on the top of Hindhead as a warning…

The ill-fated sailor, walking from London to rejoin his ship in Portsmouth, met up with three other sailors in Thursley and treated them to food and drinks before setting off again in their company. His reward was to be murdered and decapitated and thrown into a valley, where he was promptly discovered and the alarm raised. His murderers were apprehended that same day at the Sun Inn in Rake, rather unwisely selling off their victim’s clothing.

In memory of

In memory of

A generous but unfortunate Sailor

Who was barbarously murder’d on Hindhead

On September 24th 1786

By three Villains

After he had liberally treated them

And promised them his farther assistance

On the road to Portsmouth.

The Murders by the Smugglers

All through the last century, then, it seems the country from Portsmouth…was infested by gangs of smugglers.

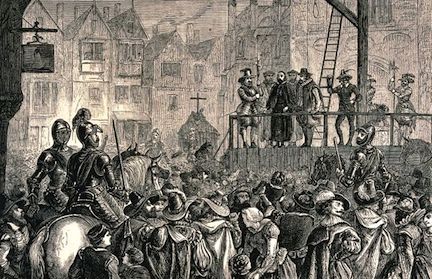

From time to time, after some unusually audacious outbreak against custom-house laws had taken place, violent reprisals were made; but on the whole the revenue officers seem to have had decidedly the worst of it, and the smugglers enjoyed an enviable immunity from the retribution of justice. The climax to this condition of affairs came on the 6th and 7th of October, 1747, when a gang of some sixty of these desperadoes assembled secretly in Charlton Forest; made a suddenly raid on Poole; broke open the custom, where a large quantity of tea which had been seized from one of their confederates, was lodged, and made off with the booty, without encountering any resistance from the surprised authorites.

Ye Smugglers breaking open ye King’s Custom House at Poole

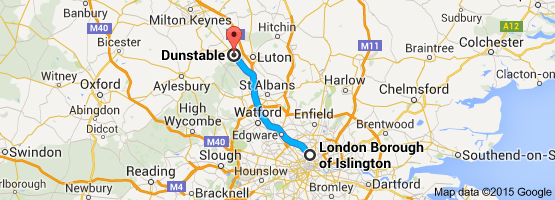

The cocky smugglers made a “riotous procession” retreating with their booty, and one of them, a man named Diamond, recognized Daniel Chater, a shoemaker, in the crowd and threw him a bag of tea. The same Diamond was taken into custody at Chichester, and Chater, having been promised a reward, was persuaded to accompany a custom house officer, William Galley, to Chichester for the purpose of identifying said Diamond.

The pair made the unfortunate decision to stay at the White Hart, where the landlady, “friendly of course to smugglers and highwaymen”, suspecting that they meant harm to her friends, sent for seven of them to intervene. Galley and Chater “were prevailed upon with force to stay and drink more rum” and when unconscious, the letter Galley was carrying detailing their errand was intercepted, and the criminals debated whether or not to murder them. Two of the smugglers’ wives who had joined the party urged them to “Hang the dogs, for they came here to hang us.”

This view of the case seems to have in an instant turned men into monsters. A devilish fury possessed the whole company. Jackson rushed into the room where Chater and Galley were sleeping. He leaped upon the bed and awakened them by spurring them on the forehead. He flogged them about the head with a horsewhip till their faces poured with blood. Then they were taken out to the back yard, and both of them tied on to one horse, their four legs tied together, and these four legs tied under the horse’s belly.

They had not got a hundred yards from the house when Jackson, in one of those sudden accesses of fiendishness continually characteristic of the whole affair, and which seemed a veritable possession of the devil himself, yelled out—“Whip them! Cut them! Slash them! Damn them!” and in an instant the whole gang’s devilish fury was wreaked on their bound and helpless enemies.

Near Rake Hill, Galley fell off the horse and was presumed to be dead, so they buried him in a foxhole in Harting Coombe. When he was found, however, his hands were covering his eyes, presumably to protect them from the dirt, so he was, in effect, buried alive.

Chater did not find so fortunate a release from his torments. He was kept for over two days chained by the leg in an outhouse of the Red Lion at Rake, “in the most deplorable condition that man was ever in; his mind full of horrors, and his body all over pain and anguish with the blows and scourges they had given him.” All this while the smugglers were calmly debating as to how they should finally make an end of him. At length a decision was come to. Subjected all the way to treatment which I cannot describe, he was taken back to the same Harris Well where it had been originally proposed to murder Galley; and after an unsuccessful attempt at hanging him there, he was thrown down it, and an end put at last to his awful sufferings by heaving stones being thrown on top of him.

The heinousness of the crime demanded swift justice, and the gang was hanged at Chichester on 18th January 1749, except for one, who died of fright the night before the execution.

The unfortunate William Galley put by the Smugglers into the Ground … before he was quite Dead

Mr Galley and Mr Chater put by ye Smugglers on one Horse near Rowland Castle

The Assassination of the Duke of Buckingham

After all this, a simple assassination may strike you as a mere church picnic. But it was at the Spotted Dog Inn in 1628 that James I’s favorite (and some say lover) was assassinated by a discontented half-pay officer who had been turned down for promotion.

It remains for me to remark that the journey of Felton to London, where he was hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn, was accomplished amidst scenes of extraordinary and many-sided excitement; and coming, as it does, before a similarly mournful expedition over the same ground on the part of the Duke of Monmouth, seems to me to cast a characteristic gloom over the annals of a road—not remarkable for coaching anecdotes or coaching records—which has been called Royal, and rightly perhaps enough,—but which has yet witnessed, so far as its historical side is concerned, and so far as my knowledge goes, gloomier and more tragic scenes than any other of the great thoroughfares out of London.

These days we have organized police forces and all sorts of high-tech devices and forensic methods to apprehend and prosecute criminals…and yet crime seems to be everywhere, even such horrific murders as described here. Are today’s criminals smarter, do you think, or were more crimes undetected back then?

Comment and enter to win Susana’s September Giveaway, a lovely necklace from London’s National Gallery (see photo at right).

Index to all the posts in this series

1: The Bath Road: The (True) Legend of the Berkshire Lady

2: The Bath Road: Littlecote and Wild William Darrell

3: The Bath Road: Lacock Abbey

4: The Bath Road: The Bear Inn at Devizes and the “Pictorial Chronicler of the Regency”

5: The Exeter Road: Flying Machines, Muddy Roads and Well-Mannered Highwaymen

6: The Exeter Road: A Foolish Coachman, a Dreadful Snowstorm and a Romance

7: The Exeter Road in 1823: A Myriad of Changes in Fifty Years

8: The Exeter Road: Basingstoke, Andover and Salisbury and the Events They Witnessed

9: The Exeter Road: The Weyhill Fair, Amesbury Abbey and the Extraordinary Duchess of Queensberry

10: The Exeter Road: Stonehenge, Dorchester and the Sad Story of the Monmouth Uprising

11: The Portsmouth Road: Royal Road or Road of Assassination?

12: The Brighton Road: “The Most Nearly Perfect, and Certainly the Most Fashionable of All”

13: The Dover Road: “Rich crowds of historical figures”

14: The Dover Road: Blackheath and Dartford

15: The Dover Road: Rochester and Charles Dickens

16: The Dover Road: William Clements, Gentleman Coachman

17: The York Road: Hadley Green, Barnet

18: The York Road: Enfield Chase and the Gunpowder Treason Plot

19: The York Road: The Stamford Regent Faces the Peril of a Flood

20: The York Road: The Inns at Stilton

21: The Holyhead Road: The Gunpowder Treason Plot

22: The Holyhead Road: Three Notable Coaching Accidents

23: The Holyhead Road: Old Lal the Legless Man and His Extraordinary Flying Machine

24: The Holyhead Road: The Coachmen “More Celebrated Even Than the Most Celebrated of Their Rivals” (Part I)

25: The Holyhead Road: The Coachmen “More Celebrated Even Than the Most Celebrated of Their Rivals” (Part II)

26: Flying Machines and Waggons and What It Was Like To Travel in Them

27: “A few words on Coaching Inns” and Conclusion