published by Rudolph Ackermann in 3 volumes, 1808–1811.

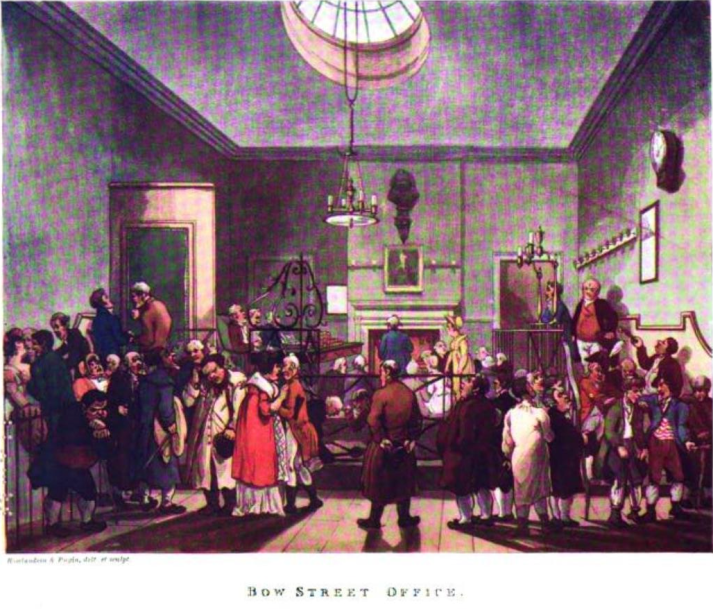

The annexed print gives an accurate representation of this celebrated office at the time of an examination: the characters are marked with much strength and humour, and the general effect broad and simple.

This office has the largest jurisdiction of any in the metropolis, its authority extending to every part of his majesty’s dominions, except the city of London, which is governed by its own magistrates.

Bow-street is, in a peculiar sense, the government office, besides acting as a police office in concert with the others, whose power extends only within a certain district. The police of this country has hitherto been very imperfect: the celebrated Henry Fielding was the first, who, by his abilities, contributed to the security of the public, by the detection and prevention of crimes. In August 1753, while a Bow-street magistrate, he was sent for by the Duke of Newcastle, on account of the number of street-robberies and murders committed nightly, and desired by the duke to form some plan for the detection and dispersion of the dreadful gangs of robbers by whom they were committed. Fielding wrote a plan, and offered to clear the streets of them, if he might have 600/. at his own disposal. The duke approved of his plan; and in a few days after he had received 200/. of the money, the whole gang was entirely dispersed; seven of them were in actual custody, and the rest driven, some out of town, and others out of the kingdom; and so fully had his plan succeeded, that in the entire freedom from street-robberies and murders, the winter of 1753 stands unrivalled during a course of many years. At this time the only profit arising to the magistrate was from the fees of his office: of the profits arising from these sources, however. Fielding had no very high opinion; after complaining that his maladies were much increased by his unremitted attention to his public duties, and having at that time a jaundice, a dropsy, and an asthma, he retired into the country, and from thence went to Lisbon, where he died. The following extract presents an agreeable specimen of that lively writer, still animated in all his sufferings, and it also gives a correct idea of the business of an active and upright magistrate at that time.

Fielding had been advised to try the Bath waters, but in consequence of the message from the Duke of Newcastle, and his exertions to free the metropolis from the desperate gangs of villains that infested it, his health considerably declined, and his was no longer a case in which the Bath waters are considered efficacious. The following account of himself and his office is from his Voyage to Lisbon:

“I had vanity enough to rank myself with those heroes of old times, who became voluntary sacrifices to the good of the public. But lest the reader should be too eager to catch at the word vanity, I will frankly own, that I had a stronger motive than the love of the public to push me on: I will therefore confess to him, that mv private affairs, at the beginning of the winter, had but a gloomy appearance; for I had not plundered the public or the poor of those sums which men who are always ready to plunder both of as much as they can, have been pleased to suspect me of taking; on the contrary, by composing the quarrels of porters and beggars, which I blush to say hath not been universally practised, and by refusing to take a shilling from a man who most undoubtedly would not have had another left, I had reduced an income of about 500/.* a year of the dirtiest money upon earth, to little more than 300/. an inconsiderable proportion of which remained with my clerk; and indeed if the whole had done so, as it ought, he would have been ill paid for sitting sixteen hours in the twenty-four in the most unwholesome as well as nauseous air in the universe.”

That this was the practice of Fielding, there can be no doubt: but that the conduct of some other justices was very flagrant, is equally indisputable; and the memory of the trading justices of Westminster, and Clerkenwell in particular, are handed down with abhorrence and contempt.

To Henry Fielding succeeded his brother, Sir John, who was many years an able and active magistrate.

Patrick Colquhoun, Esq. in his excellent work on the Police, exposed the defects of the system, and the necessity of a reform. It was taken into consideration by Parliament, and in 1792 an act was passed for that purpose, which established seven offices, besides Bow-street and the Marine Police; settled salaries were appointed to the magistrates, and the fees and penalties of the whole paid into the hands of a receiver, to make a fund for the paying these salaries and other incidental expences. This act of the 32d Geo. III. was amended by an act of the 37th, and by another of the 42d.

The present magistrates of Bow-street Office, 1808, are,

- James Reed, Esq… £1000 per annum.

- Aaron Graham, Esq.… 500

- John Nares, Esq.… 500

- Three clerks and eight officers.

It is impossible to make many extracts from Mr. Colquhoun’s valuable book. It is the basis of his system, that the numerous tribes of receivers in this metropolis are the great cause of the vice and immorality so widely prevalent, by the easy mode they hold out to the pilferer of disposing of what he has stolen, without his being asked any questions. There are upwards of three thousand receivers of stolen goods in the metropolis alone, and a proportionate number dispersed all over the kingdom.

Impressed with a deep sense of the utility of investigating the nature of the police system, the select committee of the House of Commons on finance turned their attention to this, among many other important objects, in the session of the year 1798; and after a laborious investigation, during which Mr. Colquhoun was many times personally examined, they made their final report; in which they recommended it to Parliament to establish funds, to be placed under the direction of the receiver-general of the police offices, and a competent number of commissioners: these funds to arise from the licensing of hawkers and pedlars, and hackney coaches, together with other licence duties proposed, fees, penalties, &c.; their payments subject to the approbation of the lords commissioners of the Treasury: the police magistrates to be empowered to make bye-laws, for the regulation of the minor objects of the police, such as relate to the controul of all coaches, carts, drivers, &c. and the removal of all annoyances, &c. subject to the approbation of the judges.

They recommended also the establishment of two additional police offices in the city of London, but not without the consent of the lord mayor, aldermen, and common council being previously obtained; and their authority to extend over the four counties of Middlesex, Kent, Essex, and Surry; and that of the other eight offices over the whole metropolis and the four counties also.

“It is proposed to appoint counsel for the crown, with moderate salaries, to conduct all criminal prosecutions.

“The keeping a register of the various lodging-houses.

“The establishment of a police gazette*, to be circulated at a low price, and furnished gratis to all persons under the superintendence of the board, who shall pay a licence duty to a certain amount.”

The two leading objects in the report are:

1st. The prevention of crimes and misdemeanours, by bringing under regulations a variety of dangerous and suspicious trades†, the uncontrouled exercise of which by persons of loose conduct, is known to contribute in a very high degree to the concealment, and by that means, to the encouragement and multiplication of crimes.

2d. To raise a moderate revenue for police purposes from the persons who shall be thus controuled, by means of licence duties and otherwise, so managed as not to become a material burden; while a confident hope is entertained, that the amount of this revenue will go a considerable length in relieving the finances of the country of the expences at present incurred for objects of police; and that in the effect of the general system a considerable saving will arise, in consequence of the expected diminution of crimes, particularly as the chief part of the expence appears to arise after the delinquents are convicted*.

As the leading feature of the report is the security of the rights of the innocent with respect to their life, property, and convenience, this will not only be effected by increasing the difficulty of perpetrating offences, through a controul over those trades by which they are facilitated and promoted; but also by adding to the risk of detection, by a more prompt and certain mode of discovery wherever crimes are committed. Thus must the idle and profligate be compelled to assist the state by resorting to habits of industry, while the more incorrigible delinquents will be intimidated and deterred from pursuing a course of turpitude and criminality, which the energy of the police will render too hazardous and unprofitable to be followed as a trade; and the regular accession of numbers to recruit and strengthen the hordes of criminal delinquents who at present infest society, will be in a great measure prevented.

Of the vigilance of the French system of police just before the Revolution, Mr. Colquhoun speaks highly. This system, which though neither necessary nor even proper to be copied as a pattern, might nevertheless furnish many useful hints, calculated to improve ours, and perfectly consistent with the existing laws; it might even extend and increase the liberty of the subject, without taking one privilege away, or interfering in the pursuits of any one class, except those employed in purposes of mischief, fraud, and criminality.

An anecdote related, on the authority of a foreign minister long resident at Paris, by Mr. C. will give a good idea of the secrecy of their system.

“A merchant of high respectability in Bourdeaux, had occasion to visit the metropolis upon commercial concerns, carrying with him bills and money to a very large amount.

“On his arrival at the gates of Paris, a genteel-looking man opened the door of his carriage, and addressed him to this effect: — ‘Sir, I have been waiting for you some time: according to my notes, you were to arrive at this hour; and your person, your carriage, and your portmanteau, exactly answering the description I hold in my hand, you will permit me to have the honour of conducting you to Monsieur de Sartine’.

“The gentleman, astonished and alarmed at this interruption, and still more so at hearing the name of the lieutenant of the police mentioned, demanded to know what M. de Sartine wanted with him; adding, at the same time, that he never had committed any offence against the laws, and that they could have no right to interrupt and detain him.

“The messenger declared himself perfectly ignorant of the cause of this detention; stating, at the same time, that when he had conducted him to M.de Sartine, he should have executed his orders, which were merely official.

“After some further explanations, the gentleman permitted the officer to conduct him to M. de Sartine, who received him with great politeness, and requesting him to be seated, to his great astonishment, described his portmanteau, and told him the exact sum in bills and specie which he had brought to Paris, where he was to lodge, his usual time of going to bed, and a number of other circumstances, which the gentleman had conceived could only be known to himself.

“M. de Sartine having thus excited attention, put this extraordinary question to him, ’Sir, are you a man of courage?’ The gentleman, still more astonished at the singularity of such an interrogatory, demanded the reason why he put such a strange question; adding, at the same time, that no man ever doubted his courage. M. de Sartine replied, ‘Sir, you are to be robbed and murdered this night! If you are a man of courage, you must go to your hotel, and retire to rest at the usual hour; but be careful that you do not fall asleep; neither will it be proper for you to look under your bed, or into any of the closets which are in your bedchamber: you must place your portmanteau in its usual situation near your bed, and discover no suspicion: — leave what remains to me.If, however, you do not feel your courage sufficient to bear you out, I will procure a person who shall personate you, and go to bed in your stead.’

“The gentleman being convinced, in the course of the conversation, that M. de Sartine’s intelligence was accurate in every particular, refused to be personated, and formed an immediate resolution literally to follow the directions he had received. He accordingly went to bed at his usual hour, which was eleven o’clock: at half past twelve (the time mentioned by M. de Sartine), the door of the bedchamber was burst open, and three men entered with a dark lantern, daggers, and pistols. The gentleman, who was awake, perceived one of them to be his own servant. They rifled his portmanteau undisturbed, and settled the plan of putting him to death. The gentleman, hearing all this, and not knowing by what means he was to be rescued, it may naturally be supposed was under great perturbation of mind during this awful interval; but at the moment the villains were prepared to commit the murder, four police officers, acting under M. de Sartine’s orders, who were concealed under the bed and in the closet, rushed out and seized the offenders with the property in their possession, and in the act of preparing to complete their plan.”

* “A predecessor of mine used to boast, that he made 1000/. a year in his office; but how he did it, is to me a secret. His clerk, now mine, told me I had had more business than he had ever known there; I am sure I had as much as any man could do. The truth is, that the fees are so very low, when any are due, and so much is done for nothing, that if a single justice of the peace had business enough to employ twenty clerks, neither he nor they would get much by their labour. The public will not therefore, I hope, think I betray a secret when I inform them, that I received from government a yearly pension out of the public service money; which I believe indeed would have been larger, had my great patron been convinced of an error which I have heard him utter more than once: — that he could not indeed say that the acting as a principal justice in Westminster was on all accounts very desirable, but that all the world knew it was a very lucrative office. Now to have shewn him plainly, that a man must be a rogue to make a very little this way, and that he could not make much by being as great a rogue as he could be, would have required more confidence than I believe he had in me, and more of his conversation than he chose to allow me; I therefore resigned the office, and the farther execution of my plan,to my brother.”

* This paper is called The Public Hue and Cri /, a police gazette, published every third Saturday in the month, at No. 240, Strand, and sent to the principal magistrates gratis.

† The trades alluded to are the following:

- 1. Wholesale and retail dealers in naval stores, hand-stuff, and rags.

- 2. Dealers in old iron and other metals.

- 3. Dealers in second-hand wearing apparel, stationary and itinerant.

- 4. Founders and others using crucibles.

- 5. Persons using draught and truck carts for conveying stores, rags, and metals.

- 6. Persons licensed to slaughter horses.

- 7. Persons keeping livery stables and letting horses for hire.

- 8. Auctioneers who hold periodical or diurnal sales.

The new revenues are estimated to yield 64,000/. The increase of the existing revenues is stated at 19,467/. Total, 83,467/.

* The amount of the general expence of the criminal police of the kingdom, is stated by the committee as follows:

- 1st. The annual average of the total expence of the seven public offices in the metropolis, from the institution in August 1792, to the end of the year 1797 . £ 18,281 18 6

- 2d. Total expence of the office in Bow-street in the year 1797, including remunerations to the magistrates in lieu of fees, perquisites, &c. and the expence of a patrol of sixty-eight persons 7,901 7 7

- Total for the metropolis 26,183 6 1

The other expences incurred for the prosecution and conviction of felons, the maintenance, clothing, employment, and transportation of convicts, to which may be added the farther sums annually charged on the county rates, amounted in 1797 to 215,869 13 10|